So all nature awaits the return of Spring,. Whether it be the crow in his flock, the wasp in her sheltered cranny, the muskrat in its cave by the water, the rich thick sap in the root of the tree, or the stored up life in the bulb, they all await the one far-off divine event. For back of all Nature there lies a Power that has been and is and is to be. What, after all, do we mean by Nature but the sum total of all these manifestations of purpose, of foresight, of helpfulness, of striving for higher and ever higher levels?Why does evolution mean life more abounding , and degeneration mean atrophy and death, if there be not, pervading the universe, a power, a principle, a stimulus, a goal?

And shall we, as did the Hebrew tribes of old, falter to speak the ineffable name? Shall we not rather worship Him humbly as we see His power, thank Him gratefully that we have been permitted to think His thoughts after Him, look up to Him confidently for that we have come to see how He has infused us with Himself, and lovingly call him Father and God?

SO SOON AFTER MY ENCOUNTER WITH THE EXISTENTIAL STRUGGLES OF CHARLES MONTGOMERY SKINNER, IT WAS A BIT OF A SHOCK TO MEET HIS NEAR-POLAR OPPOSITE, SAMUEL CHRISTIAN SKINNER. This chemist, evolutionary biologist, Nature Study advocate, and theologian was Christian in more than middle name. Indeed, arriving at the passage above on the final pages of “Under the Open Sky”, the reader is tempted to conclude that, for Schmucker, getting close to Nature was primarily a vehicle for having a religious experience. While it is tempting to write him off as a Bible-thumper, in fact, Schmucker occupied an odd corner of the Biblical creationism / biological evolutionism controversy of the time. Viewing God as immanent in Nature, Schmucker was quite comfortable with speculating about the evolution of the hummingbird on one page, and then making a reference to the Hebrew Bible on the next one.

ULTIMATELY, THOUGH, HIS RELIGIOUS ZEAL LEFT HIM PRONE TO AN OVERLY ROSY OUTLOOK ON HUMAN PROGRESS AND ITS IMPACTS ON NATURE. In one early passage in this book (which explores nature from the conventional seasonal perspective so popular at the time), Schmucker even declared that “in the newness of the times we are growing back to a touch with nature; a tender, sympathetic, spiritual touch, closer than any of our forebears ever knew.” Perhaps humans had managed nearly to wipe out most of the larger mammals due to overhunting, but ultimately, humans are part of a larger purpose, allied with God in shaping nature. Consider a fruit orchard:

God set the plan for the fruit-trees and we have carried it out. Rarely has man worked better along lines laid down by the Creator. The original trees were doubtless hardier, but that was because they had to take care of themselves. We have relieved them of that necessity, and the new strain has responded to our kindness and rewarded most magnificently man’s skillful endeavor. So it comes that every little country home is glorified at each return of spring by the gorgeous beauty of the blossoming trees,

UGH. I confess it was tough getting through some of this. Schmucker’s natural world is nearly an Eden of human progress and prosperity. Consider the even-tempered tone of this passage, in which Schmucker contemplates how many larger mammals are mostly gone, while the smaller ones are thriving:

The whole rodent family, of which the squirrels are important members, is a striking example of the safety that lies in insignificance. There are more species of rodents than of all other fur-bearing animals combined. Man’s incursions into a neighborhood simply seem to relieve them of their enemies. Rabbits and squirrels are perhaps more abundant to-day than they were when the Indians roamed our forests. Certain it is that the advent of man in the Northwest increased the numbers of the Jack rabbits. This set of animals is unusually adaptable to all the varied possibilities of life…. So they have found for themselves a secure footing where the bear and the woolf, the deer and the bison have failed.

IF THE BISON “FAILED”, THEY WERE HELPED ALONG BY INCESSANT HUNTING FOR SPORT BY ANY WHITE MAN WITH A GUN WHO HAPPENED TO SEE THEM. But while I highlight these passages, it is not completely true that Schmucker has failed to see what humans have done to American nature. For instance, in writing about birds in the Middle Atlantic States, Schmucker acknowledges the Audubon Society and the Nature study movement in public schools as forces that have helped reduce hunting pressures and lead to a generation of birds less fearful of humans. But again, there is strangely little remorse about what has happened. If humans are merely tools of divine purpose, then perhaps it is simply a matter of divining the purpose as to why humans carried out such slaughter of animals for so long a time.

BEFORE I CLOSE, A FEW KINDER WORDS FOR SAMUEL CHRISTIAN SCHMUCKER ARE IN ORDER. This book certainly provides abundant information about aspects of nature for perhaps a middle school or high school reading audience, though it is hardly comprehensive. (It favors rural nature in fields, orchards, and yards over a wilder nature of forest, swamp, and mountainside.) It covers diverse species — mammals, birds, insects, reptiles. And most significantly, I think, it makes a case for organisms that were heavily disliked by most people then (and largely still are, today). For example, in keeping with Schmucker’s purpose-driven outlook on Nature, even the poison ivy has innate value:

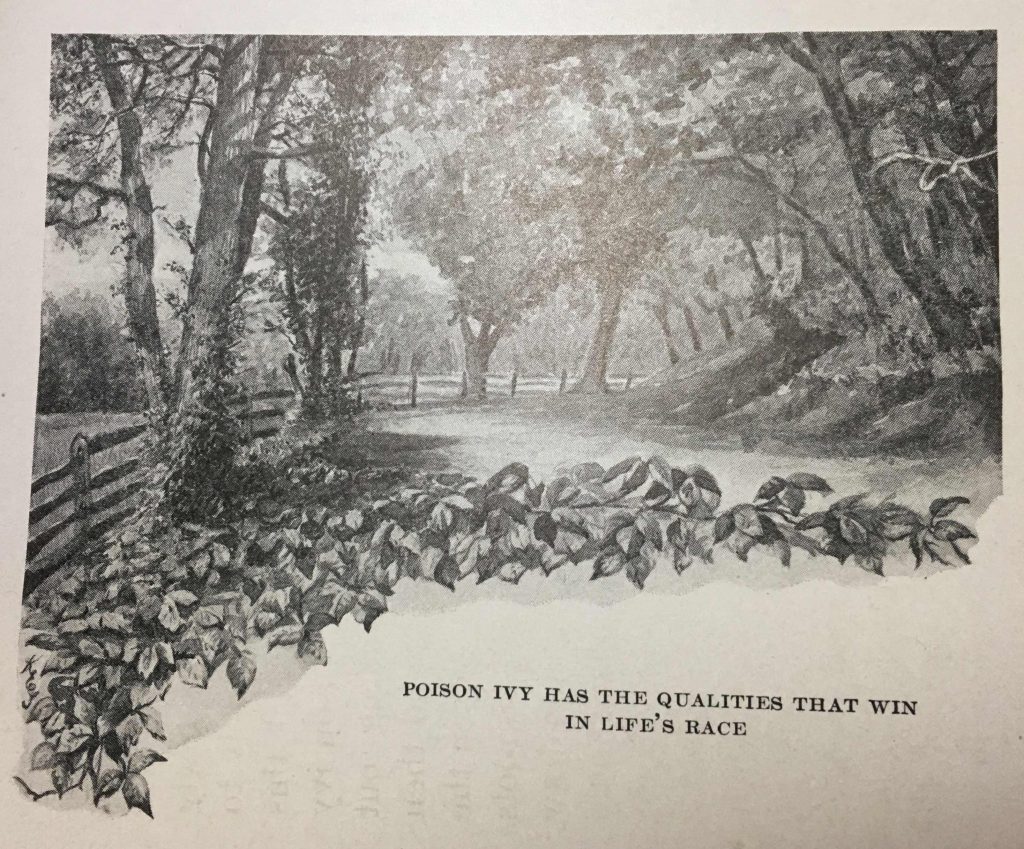

[Fall] is perhaps the most tempting season of all the year for a walk, and a country lane beneath the trees is never more lovely. But there is a serpent in this Eden, in the form of a creeping, enticing, but trouble-breeding vine.

Poison Ivy is a bold bad plant. It seems so subtle in its attacks, so bitter in its hatred, that we can hardly help believing it our sworn enemy. But this is only our view of the matter, and plant lovers all know there must be another side to this story. From its own stand-point the plant surely is most ingenious. That it is successful is evident from its abundance. Unless relentlessly weeded out by man, it covers our fence-posts, climbs the trunks of our trees, and clambers about our road-sides.”

What follows is a lengthy section of text enumerating poison ivy’s good points: it has managed to make do with relatively little material in its stem (relying upon various trees for its support), and it provides white berries for birds to eat. These qualities, together with its poisonous oil, have helped insure that the plant is a winner “in life’s race”. The image below, along with many others throughout the book, was done by the author’s wife, Katherine Elizabeth Schmucker.

FINALLY, A FEW PARTING WORDS ABOUT MY COPY. I read a “first edition” from 1910, apparently in very good condition. Not only was it unmarked by earlier owners, but also many of its pages had not even been cut. The paper, however, has clearly deteriorated over time, and is brittle and tears exceedingly easily; one post-it tab I placed on a page, when lifted off, removed a piece of the page, too. The illustrations are quite pleasant, but apart from the title page, not overly inspiring. Even the cover, while colorfully decorated, strikes me as somewhat bland. I suppose the apparent newness of the volume from 1910, its abundance of illustrations, and the relatively unknown nature of the author (who does not have a Wikipedia page yet) left me hoping for great things. I am afraid I am walking away rather disappointed — though, unlike the original owner at least, I did read the book cover to cover. It just didn’t live up to the grace and beauty of its title page.