At last, after a year-and-a-half away, I return to my quest — an exploration of the fascinating lost world of the golden age of American nature writing. Beginning with Thoreau’s passing in 1861 and extending until WWI, this time period is historically interpreted as being a wasteland of nature writing. There was John Muir, of course. And for the more intense environmental writing aficionados, there was the other John, John Burroughs. But otherwise, there are no authors typically identified as writing in the genre until Aldo Leopold’s groundbreaking “Sand County Almanac” was published in 1949. True, there aren’t as many naturalist essayists between the two world wars (I have found a few, and will visit them from time to time). But it turns out that the first few decades of this time period were fecund with nature essays — a rich array of magazine articles, and a plethora of delightfully obscure authors, many of whom corresponded with and visited each other. What is even more gratifying is that the writers’ very obscurity makes this adventure possible. I am striving to read original copies — first editions if I can, period texts if not — of as many of the books as I can afford. During my absence, I have discovered hitherto unknown troves of book titles, including a collection from the Library of Congress holdings. I am so excited to return to this bygone era. The books are stacked on my desk and crowded into my bookcase. Let’s get underway!

My first selection is one of several works by Ernest Ingersoll that I now own. According to the font of all knowledge (a.k.a., Wikipedia), Ingersol was an American naturalist, writer, and explorer who lived from 1852 until 1946. He published nearly two dozen books, mostly in the nature essay vein. He began his career in academia, under the tutelage of Louis Aggasiz at Harvard University. He served as Zoologist on the Hayden Geological Expedition to Yellowstone in 1874. Returning East, he wrote up his discoveries from the trip, mostly mollusks. He also became a staff reporter for the New York Tribune and contributed articles to a periodical that was the antecedent to Field and Stream. He traveled west again in 1877 and 1879, reporting on his experiences. He also embarked on a project reporting on US shellfisheries for the US Fish Commission and US Census Bureau. He subsequently became a popular nature essayist and lecturer. Friends Worth Knowing was his very first foray into the genre.

The book is quite an eclectic affair. There is no clear structure to the essay collection — it appears to be a compilation of previously published articles, sufficient to justify a book title. Given the author’s molluscan predilections, it is not surprising that the first chapter, In a Snailery, is a visit with gastropods. A later essay explores the lives and habits of wild mice species. There is also an essay on bison and their fate. One less-memorable essay reports on various accounts of domesticated animals finding their way back home over long distances. Another essay, toward the end of the book, considers the “civilizing influences” of western culture at the time (more about that ahead). The rest of the book’s offerings are largely ornithological in scope.

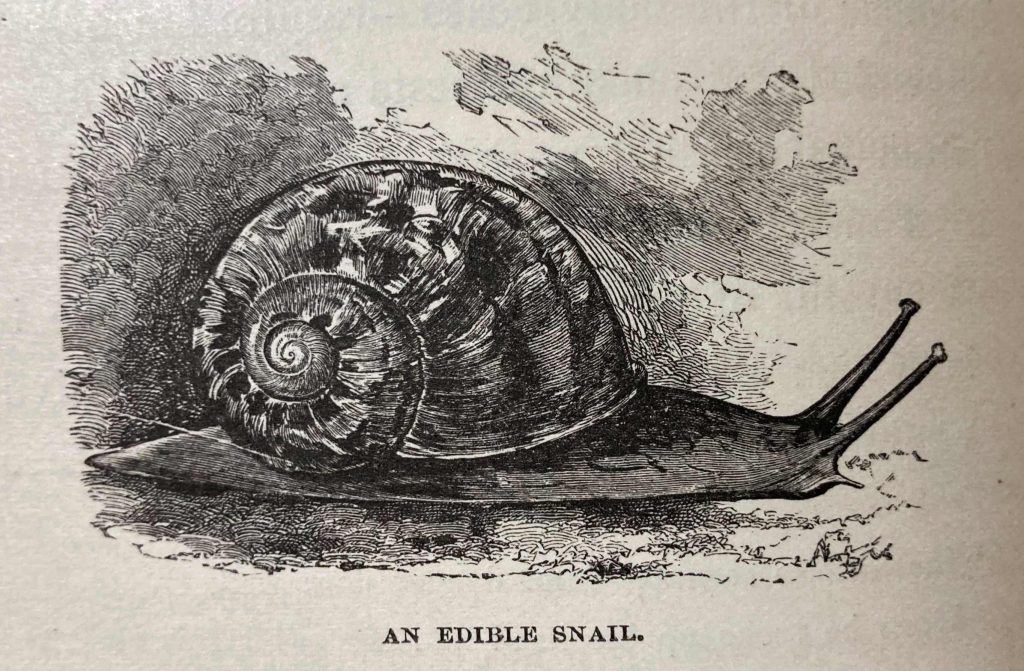

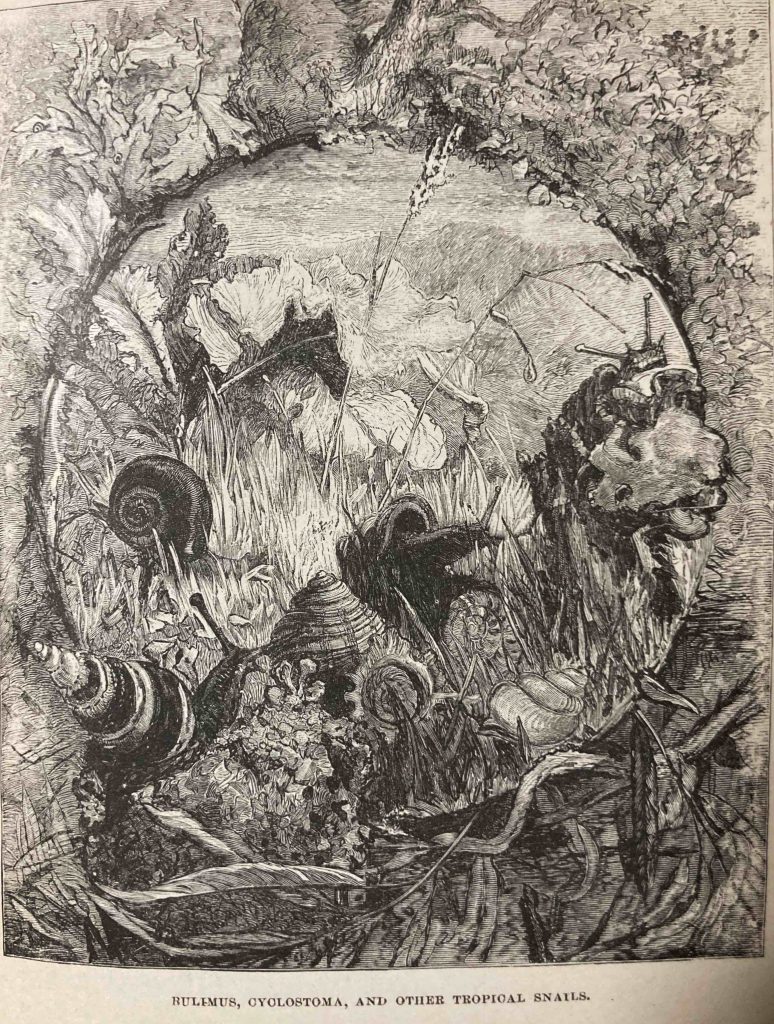

I have to say that In a Snailery sets a fairly high standard for the volume. The engravings are my favorites in the book. Indeed, many other chapters had few engravings at all, and the artwork isn’t of the same quality of detail. Some of the snail engravings are visually packed (such as the tropical snails below), but my favorite is probably an edible snail making its way across the middle of a page, sans slime trail.

I quite enjoyed Ingersoll’s pronouncements about the merits of snails, too. He observed on the first page that “Snails are of a vast multitude and variety, ancient race, graceful form, dignified manners, industrious habits, and gustatory excellence…” I appreciated how Ingersoll enthusiastically set out to counter what was likely a general disgust or disinterest with snails, apart from their culinary potential. His prose is thoughtful and observant as he details the life cycle of the snail and then considers its long evolutionary heritage, going back to an origin “when dark forests of ferns waved their heavy fronds over the inky Paleozoic bogs. Distance disappears in the presence of such prodigious time.” Along the way, his essay points out where the reader might find snails in the wild. This is not the last time in the book that Ingersoll encourages readers to venture out into nature on their own. While the essays share Ingersoll’s own observations, his intent is, at least in part, to offer a gentle nudge to his readers.

His second essay, First Comers, is about the first birds of spring that he encounters in his New England home. “To the lovers of long rambles in the woods and meadows,” he announces, “…every indication of approaching spring is eagerly scanned, and is hailed with delight.” HIs enthusiasm and sense of familiarity with the birds he writes about are evident in descriptions like this one, of a house wren: “…this little bobbing bunch of brown excitement is the very spirit of impudence.” After introducing a number of bird species, he turns to the chipping sparrow. Here, he remarks that “The chippy is so easily watched that I do not propose to tell all I have learned about it, and thus rob a reader of the pleasure of learning its beautiful ways for himself.” I appreciate, again, how Ingersoll seeks to guide his readers, but ultimately toward making their own discoveries.

Throughout the book, Ingersoll gestures toward many contemporaries and near-contemporaries in the natural history field. At various points, he mentions H.D. Thoreau, John Burroughs (quoting a letter Ingersoll received from him), Alfred Russel Wallace, and Dr. C.C. Abbott (whom I have visited before in this blog, and will return to frequently in upcoming posts). He mentions many other people, too, who appear to have shared anecdotal information about nature with him. I continue to appreciate how there was a vibrant nature study community present in the US during this time period.

Jumping over some ornithological writings (there will be plenty of those in the blog posts ahead), we come to The Buffalo and His Fate. The essay purports to be a review of another scientist’s report on the status of the bison, but it is difficult to determine what Ingersoll is offering second-hand and what is based upon his considerable time in the West. He opens the essay with a grim prognosis: “Its history has been a tale of its extermination, and a very short time will be likely to see the last of these noble beasts roaming over the plains.” Then, at the close of the essay, he notes that the remaining bison are now in two main herds– northern and southern. Considering the southern herd in Texas (which, at the time, was occupied by understandably hostile Indians), Ingersoll coldly noted that “…unless legal interference be quickly made and strict regulations enforced, the fate of the buffalo south of the Platte will be a repetition of its history east of the Mississippi — speedy extermination.” And here is where I realized the extent to which Ingersoll’s era is quite foreign to my own. Nowadays, such an announcement would be followed by exhortations to take action. Surely, Ingersoll’s readers might send letters to their Congressmen urging such safeguards for the remaining bison? Yet instead, Ingersoll resolutely accepts their inevitable demise. This was not an age for environmental activism. The certain march of Western progress was not to be questioned. Along the way, there might be casualties, but they were unavoidable.

This outlook is even more blaring in Civilizing Influences, where Ingersoll seeks to convince his readers (and maybe himself, too) that Western progress is not all bad. Sure, most wild quadrupeds were being wiped out (other than the mice) and hawks, owls, and snakes were routinely killed by farmers, but the songbirds “seem…to recognize the presence of man’s civilization as a blessing.” In a mix of accurate science, anecdotal observations, and dubious theorizing, Ingersoll presents the premises of his argument. Less forest means a less rigorous climate (huh?) and more sunny spots where birds prefer to place their nests (really?). Plowing exposes more insects for birds to eat, while orchards likewise encourage insects to thrive. Horses, cattle, and sheep droppings provide food and homes for beetles that many birds feed upon. Fewer avian and reptilian predators make it easier for the birds to survive. In fact, not only are songbirds thriving, Ingersoll asserts, but they are singing more, too. We are civilizing them! “By making their lives less laborious, apprehensive, and solitary, man has left the birds time and opportunity for far more singing than their hard-worked, scantily-fed, and timorous ancestors ever enjoyed….”

I will not leave Ingersoll there, in the baffling heart of his own longing to exempt Western civilization from all the accusations of environmental damage that might be levied against it. After all, here he was merely echoing ideas that were all too popular at the time. I will offer up, instead, this charming portrait of the musical enchantment available to the rambler out-of-doors on a New England April day: “[The song sparrow’s] clear tenor, the gurgling, bubbling alto of the blackbirds, the slender purity of the bluebird’s soprano, and the solid basso profundo of the frogs, with the accompaniment of the April wind piping on the bare reeds of winter, or the drumming of raindrops, form the naturalist’s spring quartette — as pleasing, if not as grand, as the full chorus of early June.”

I will close with a paragraph about my particular copy of this book, which has a bit of history of its own. The bookplate is that of Jonathan Dwight, Jr. (actually Jonathan Dwight V), 1858-1926, founding member of the American Ornithologist’s Union and ultimately its president. His ornithological collections were housed in the American Museum of Natural History. After his death, his extensive ornithological library found its way to the Smithsonian in 1970. I am assuming this particular volume didn’t make the cut, and instead remained in private hands.