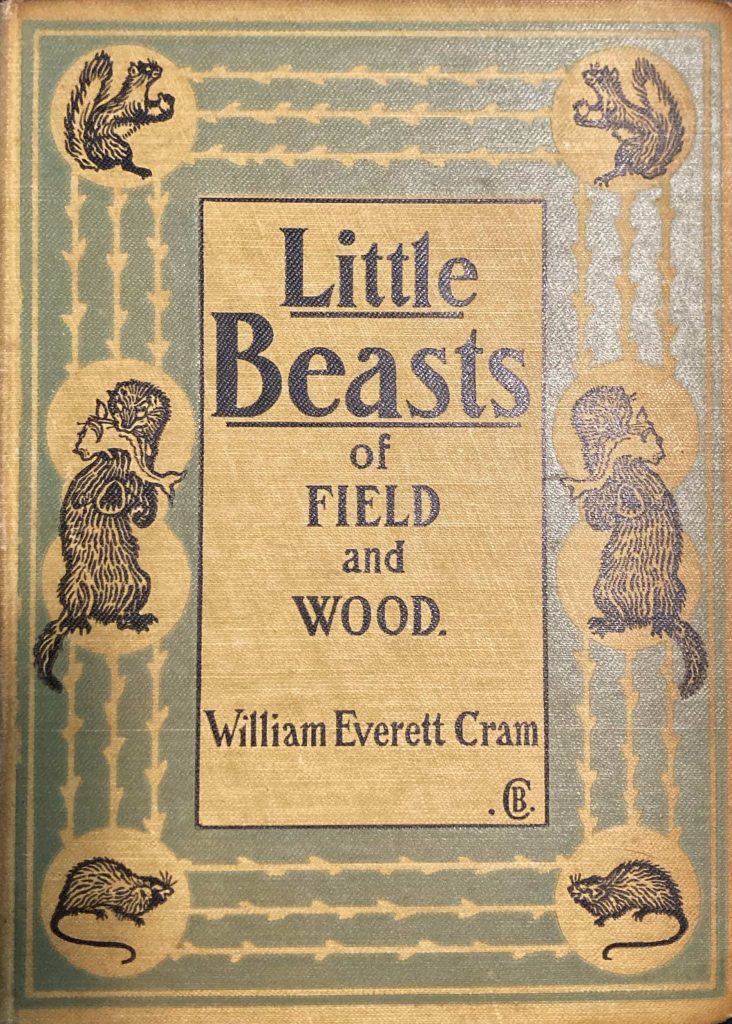

As obscure nature authors go, William Everett Cram (1871-1947) is one of the most enigmatic. I know that he was an author and illustrator, identified in a long list of credible nature writers identified by Theodore Roosevelt during the Nature Faker Controversy (stay tuned to this blog for more about that). I know that he illustrated Witmer Stone’s American Animals, published in 1902. He also illustrated Charles Conrad Abbott’s Bird-Land Echoes(1896), which likely explains why Cram dedicated his own first book, Little Beasts of Field and Wood (1899) to Abbott. Cram would go on to publish a sequel with still more “little beasts” more than a decade later, and then Time and Change (described by one bookseller as “farming essays”) more than a decade after that. I know that he spent most of his life in New Hampshire, and that, as of August 15th, 1899 (when he penned the preface to his first work), he was living in Hampton Falls, along the coast just north of Seabrook.

I was intrigued by this title, though the book’s small size, cover design, and title made me fear at first that the work was aimed at children. Even given a potentially greater vocabulary of youngsters about 125 years ago compared to now, this book still strikes me as primarily geared for older youths and adults, however. Though it is a collection of animal profiles like those of Ernest Thompson Seaton, it is a far cry from his children’s tales (expect reviews of his work in the future, also). He opens the work with this keen observation:

To my thinking, the small beasts that still inhabit our woods have been altogether too much neglected by the student of nature, though really much nearer to us and much more easily comprehended than birds, when you have once succeeded in finding them. For that they are more difficult to observe than birds is undeniable.

Indeed, having read now in excess of 60 nature books, I can attest to the fact that most of the attention is usually given to birds and/or plants. Many of the animals in this book, such as otters and muskrats, rarely receive any attention whatsoever from other writers. Most of them received plenty of attention from trappers, though; in the case of minks, for instance, Cram noted that their wild numbers fluctuated inversely with how much their pelts were in style at the time. Indeed, Cram himself clearly hunted and trapped quite a few of his subjects. The book is entirely illustrated by him, and many of the animal poses suggest that they were drawn from dead specimens rather than live ones. Interestingly, Cram never mentions using an opera-glass (as the birders at the time largely did). He does speak frequently of reading animal tracks, and he also reports animal sightings relayed to him by other trappers. His own dedication to careful, patient observation is attested to by his noting that Thoreau himself saw few foxes, while Cram encountered them frequently. (He discounted the possibility that they were less abundant in Concord half a century earlier, though I would think that question merits further research.)

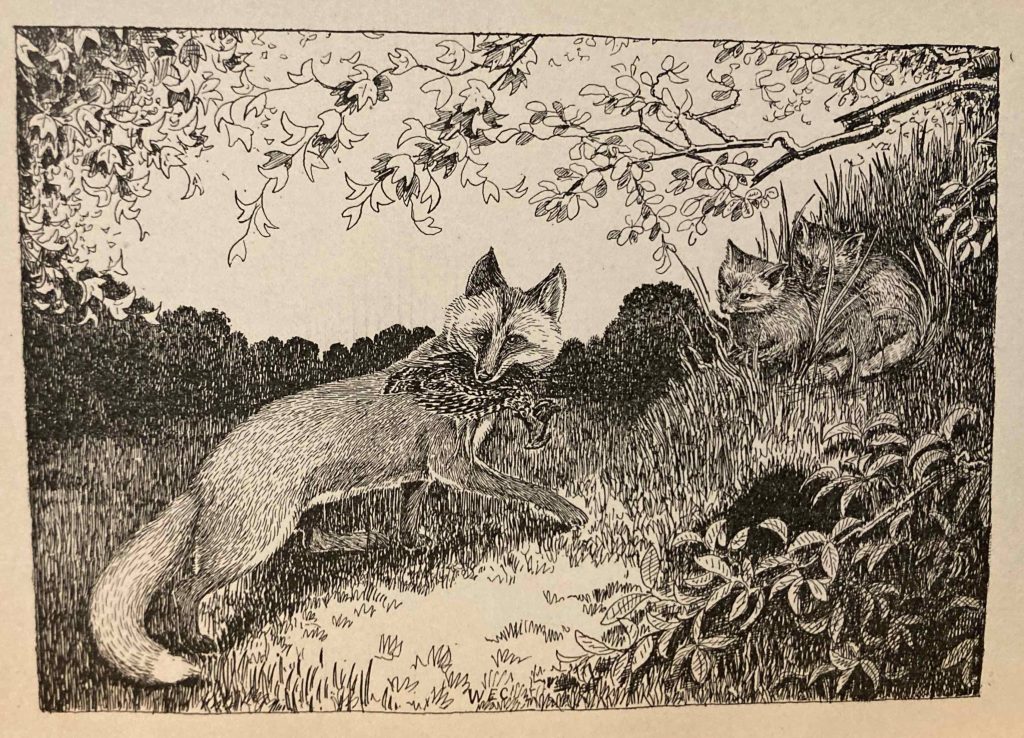

As I noted earlier, I found Cram enigmatic from the start. I sought to get to know him through this book, and for most of it, he remains quite aloof. His prose is consistently clear, but without sparkle; its workmanlike quality evokes most field guides I have viewed. So we will skip over most of the volume to its very last chapters, where he finally comes to life in reporting on the ways and habits of squirrels. Perhaps this is, in part, because squirrels were more commonplace about the home than, say, weasels would have been. And perhaps they are more endearing by nature. Whatever the cause, his fondness for squirrels (relative to foxes, in this case) is evident from the two images below. The one on the left is of a fox bringing food to its young; note in particular the manner and expressions of the pups. Compare that with the right-hand image, of a mother red squirrel stripping seeds from a pine cone while her two adorable offspring look on expectantly.

In one of my favorite passages, Cram notes about the red squirrel’s diet that it “seems to include pretty nearly everything that is ever eaten by any of our native animals. I have known them to find their way into the pantry of a farmhouse, and sample everything available, appearing to be par- ticularly well pleased with the custards.” I don’t know about Cram, but that is certainly a fondness I can identify with, myself.

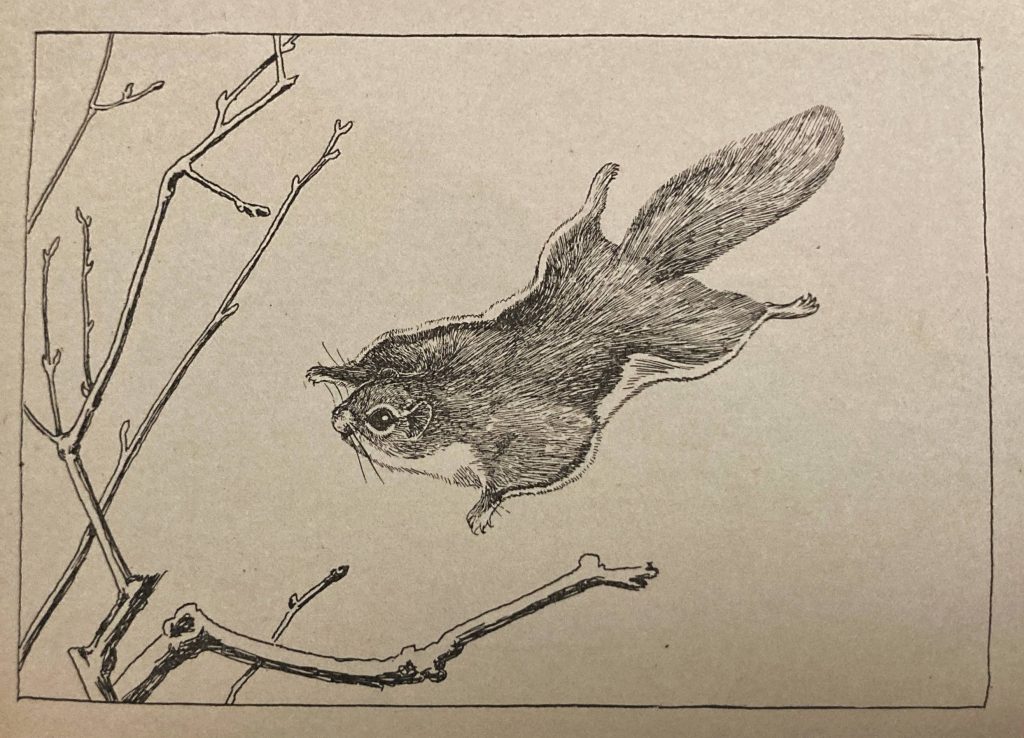

But Cram saves his confessions of delight for the flying squirrels. While he notes that they seem to act “wholly upon instinct and without displaying the slightest symptom of intelligence”, he still confesses that “for all that, there are no more attractive or winning creatures in the woods. They never exhibit any marked symptoms of fear, but just cuddle up on a knot or projecting piece of bark only a few feet away, looking as if they would like nothing better than to be taken in the hand and petted.” He follows this declaration with a charming story from his grandparents (the first and only time they appear in this book):

I remember hearing my grandmother tell how one winter evening she was sitting before the fire, when my grandfather came home from the woods and taking off his coat threw it across a chair near the fireplace. Presently a flying squirrel crawled out of one of the pockets, sailed across the room to where she sat, and nestled contentedly in her hair, which she wore in a great fluffy mass piled high above her head. I cannot recall the sequel of the story, which was undoubtedly interesting, at all events to those chiefly concerned in it. No one ever knew exactly how the squirrel came to be in the coat, but it was supposed that a family of them must have been disturbed by the choppers in the woodlot and that this one had taken refuge in my grandfather’s pocket, probably bereft of what little wit it ever had by the noise of chopping and the crash of falling trees, and glad to find any retreat away from so rude a world. Perhaps it was only half awakened from its winter’s sleep, and dozed off again as soon as it found itself finally ensconced in the depths of the pocket, to be aroused later by the heat of the fire. I cannot help wondering what finally became of it, and just how much of an impression the adventure made upon its sleepy little brain, or whether it took it all as a matter of course, to be forgotten as soon as it was fairly back in the trees again. Perhaps I have run across some of its descendants in the woods or caught them in box-traps without mistrusting that their ancestor and mine had once been on such very intimate terms.

By the final paragraph of the book, Crum’s neutral tone has vanished completely:

It is now several years since I have seen a live flying squirrel, though there is no reason to suppose that they are any less abundant than formerly. I have rapped on hollow trees and pried into decaying logs and stumps on every occasion without discovering the sleepy little chaps I was in search of. But this sort of thing goes largely by chance after all, and to-morrow I may happen on them where I least expect it. I remember once climbing to a crow’s nest in a tall pine while the old birds wheeled and scolded overhead. When rather more than half-way to the top, I reached the place that I had seen from the ground, but was disappointed to find only a last year’s nest heaped up with dry leaves and pine-needles in such a way as to show that it had already been appropriated by squirrels. On investigation, I founds instead of red squirrels as I had expected, four or five little flying squirrels about half-grown. I only saw them for a few seconds at most, as they scrambled away in all directions and disappeared completely. But in those few seconds I became aware that young flying squirrels are simply the most delightful things in existence. And I still look forward to the time when I shall discover another family of them, without the slightest fear of being disenchanted.

In closing, a word about this volume. It bears only one small mark from its past: impressed into the back of the frontispiece is the single word, Gorman. Alas, it is not sufficient for tracking down the previous owner.