No other objects in inanimate nature touch so many hearts tenderly, like the actual presence of dear friends, as flowers. Not children alone, but men and women often look upon them with attributes not possessed by other inanimate objects. It does not seem out of place to talk to them any more than to talk to young children.

I like to picture Eldridge E. Fish (a challenge made difficult by not finding any online images of him) strolling a park in Buffalo, New York, greeting the blooming asters as he wanders past them. In a book with few interesting passages or scenes (more anon), here is a moment of true oddity. A few sentences later, though, his prose returns to its bland, though solid, form, and what little sense I have of Fish as a naturalist and scientist disappears again.

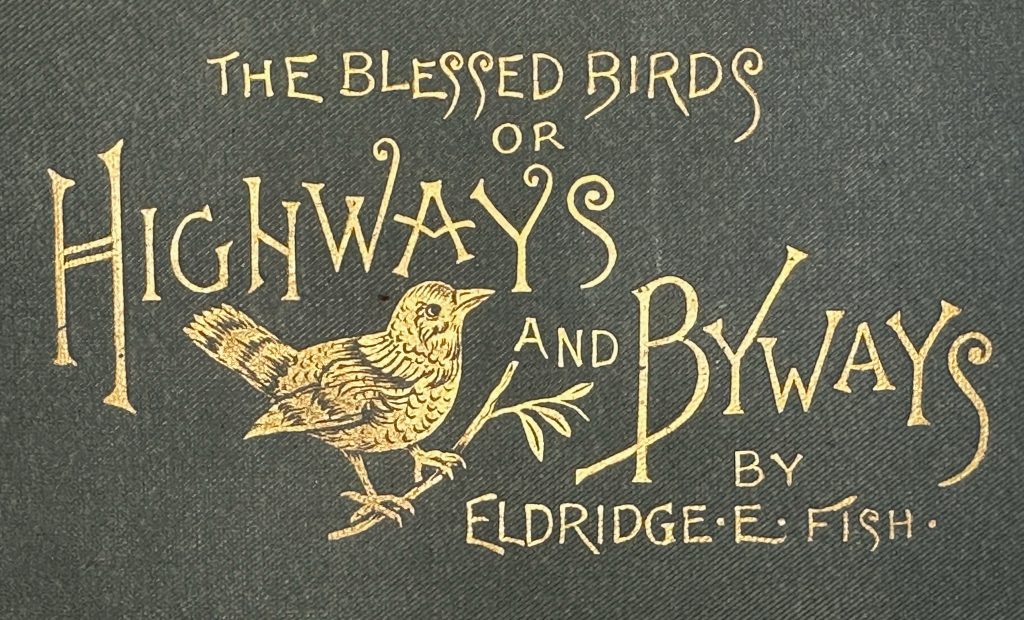

The Blessed Birds, or HIghways and Byways (1890) appears to have been Fish’s only work. I would call it his magnum opus, but I would not dare to apply that to his fairly slender volume. Fish contributed occasional pieces to the Buffalo Sunday Currier newspaper and a couple of other publications, and at some point, he decided to compile them into a book, locally published by Otto Ulbrich at 396 Main Street in Buffalo. The result is uneven but serviceable. The essays draw upon the usual cast of fellow natural history writers: Thoreau, Burroughs, Abbott, and Torrey. And we mustn’t forget Wilson Flagg, who is responsible for this horrendous poem that opens one of the pieces in this volume:

Bird of the wilderness, dearer than Philomel;

Echoes are telling thy notes from the hill and dell;

Lovers and poets delighted are listening

When the first star in the dewdrop is glistening,

Waiting the call of the eremite forester,—

Lonely, nocturnal and sentinel chorister!

Prophet of gladness, but never foreboding ill,

Caroling cheerily from his green domicile,

Uttering whippoorwill, whippoorwill, whippoorwill,

Sibylline, tuneful, mysterious whippoorwill.

But I wander. The purpose of this post is to explore Fish’s natural history work, not his taste in 19th-century poetry.

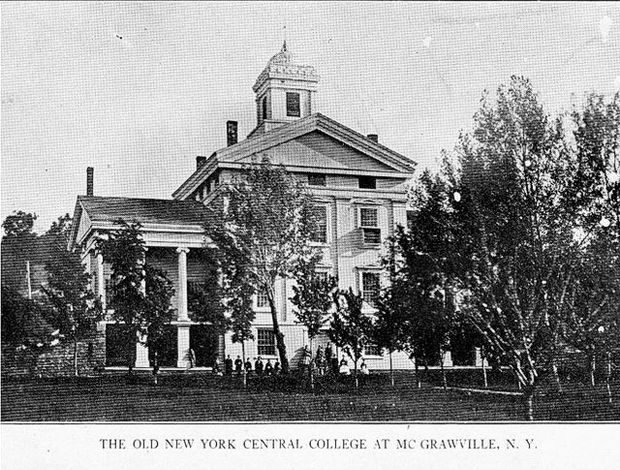

Not surprisingly, there is no biography of Fish — not so much as a Wikipedia entry online. Finally, I found him via a Wikipedia page on New York Central College, a predecessor to Cornell that existed for ten years in Upstate New York. It was an abolitionist institution that welcomed all qualified students, one of whom was Eldridge Fish. In the Wikipedia article, Fish is described as a “scientist and school principal”. Fortunately, there is also a reference citation to a Buffalo Currier newspaper article on Buffalo area schools and their principals, which includes a couple of paragraphs about Fish. It notes that he was born in Otsego County in 1829, and raised on his father’s farm in Cortland County. In 1871, he became principal of School No. 10 in Buffalo, a position he still held in 1894. He wrote papers on botany and ornithology, and “Many of his best papers have been printed in the Courier.” Several of his students went on to Harvard and Cornell.

Unfortunately, publishing the book did not grant Fish any lasting fame. His greatest moment of success was probably on July 23rd, 1890, when Dr. John Johnston of Bolton, England visited John Burroughs at his summerhouse, Slabsides. Strewn about the table and seats were a number of magazines and books, including a copy of Fish’s The Blessed Birds. Did Burroughs actually read it? If so, did Burroughs manage to finish it?

Fish is at his strongest when offers condemnation of the ongoing destruction of forests and songbirds. Regarding logging of woodlands, Fish observes how that results not only in damage to the rural scenery but also impacts the local hydrology and climate. Here, I wonder if he might have been inspired by George Perkins Marsh, who was widely read in the last few decades of the 19th century. Fish is even more troubled by the loss of songbirds, titling an essay, “Danger of an Early Extinction of Song Birds”. He attributes their dwindling numbers to the clearing of forests, the invasion of English swallows, the killing of birds for food in the American South, lighthouses and the Statue of Liberty’s torch, the hunting out of larger game birds, ornithologists gathering bird skins and eggs for their collections, and (of course) the millinery trade. “God no more created the birds for you and me than he created you and me for the birds,” he declared. He also astutely noted that “Men are generally slow to realize the danger of losing that which is apparently abundant, especially if it costs nothing.” That sentiment is equally true today.

Before I allow Fish to return to his well-earned obscurity, I will share one other passage of note. Like many nature writers of his day, Fish advocated for readers to get outside and notice the wonders of their own backyards:

The orchard assists in teaching the lesson that objects which yield the greatest pleasure lie nearest our doors; that it is not necessary to make long journeys or to explore far-off countries to see the most interesting objects in nature. I can find more of interest in Limestone groves, in Wende’s woods and meadows and in the vicinity of Portage than I can in the Adirondacks, the wilds of Northern Michigan or the primitive forests of the Carolinas. Even this old orchard of less than a dozen acres has so many charming things growing and living, flowerless and flowering, winged and four-footed in it, that a Gray or a Nuttall would find it a field of delight and study. There are mosses on the north side of the tree trunks and lichens pendant from leafless branches. Tall ferns are growing in a shaded corner of the lot near a rivulet of pure water, and their broad fronds are as green and thrifty as in the shady woods. The jewel weed, with almost transparent stem, and leaves that look like silver, when immersed in water, are abundant and luxuriant.

Finally, in closing, a word about my copy, from 1890 — likely a first and only edition. Its green cloth cover includes this charming gold-embossed title with a picture:

What is more, my copy is signed — a bit tentatively, perhaps — by the author, with his kind regards: