As Memorial Day approaches yet again, the naturalist’s thought turns to how we memorialize those our nation has lost in wars. We construct monuments of granite and marble, polished stone faces with lettering that has come to signify, in our culture, the tragic reality of death, of loss. Perhaps on Memorial Day we might visit a memorial, brush our fingertips against the cold stone letters, and touch, for a moment, our own inevitable mortality. Perhaps even while standing beneath an appropriately leaden sky, we weep for the enormity of our losses along the path to maintain the freedom we first fought for over two hundred years ago. And while we weep, the chainsaws growl, and another tree falls in a stand of forest that stood untouched for the past fifty years or more. Bulldozers scrape their way across the land, and the forest is forgotten.

There is another way.

There is a way to honor our fallen and also to protect and cherish the living forests all around us. It is a model whose roots go back at least to ancient Greece, and probably further. The Greeks (and many other civilizations) maintained sacred groves, patches of forest where they could approach the great Mystery through ritual. The forest was a place for spiritual connection — an awareness not lost on Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon religion, who had a vision of God and Jesus while praying in a ten-acre beech grove on his family farm in 1820. As a result of this vision, that patch of forest is now cared for and protected. As Donald Enders writes in an article at www.LDS.org, “The Sacred Grove is one of the last surviving tracts of primeval forest in western New York state….. The Church has for some years been directing a program to safeguard and extend the life of this beautiful woodland that is sacred to Latter-day Saints.” Along the streets of Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, and many other towns and cities across the United States, trees have been planted to honor the deceased. Beside the trees, small stone plaques bear a name, a few words of remembrance, and birth and death dates. Within this tradition, the idea of honoring the dead through caring for the living still remains. The next step back to the grove would be to recognize healthy, mature forests as being fitting sacred sites.

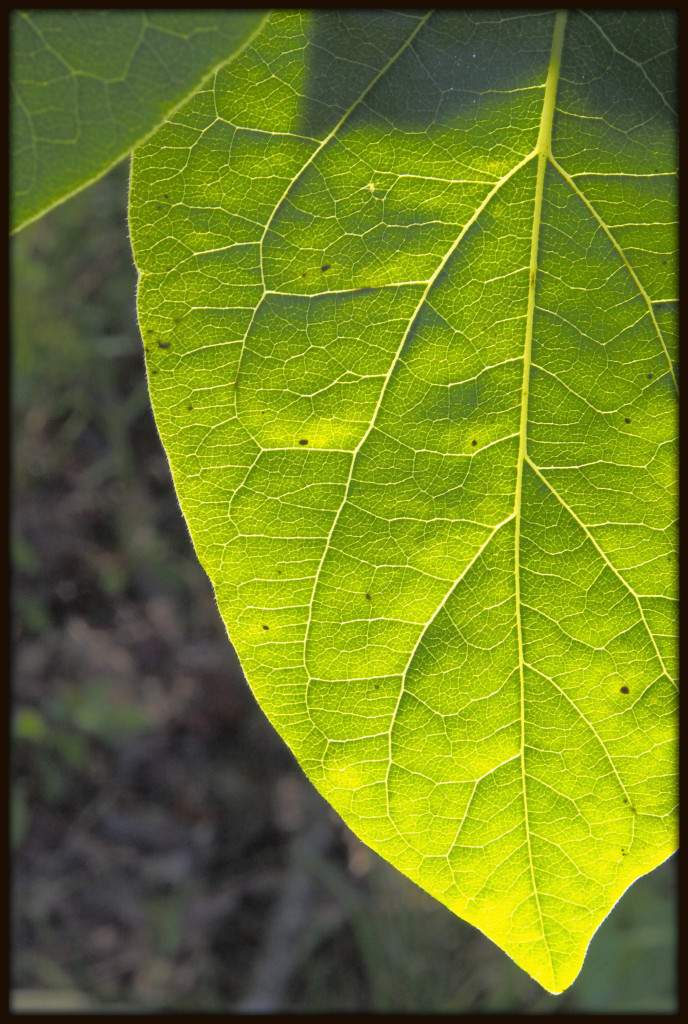

Through dedication ceremonies and markers in the forest, they can become places to acknowledge our losses while celebrating life’s continuance, in leaves of an oak and flowers of a tulip poplar. It is this very idea that Joan Maloof proposes in Teaching the Trees: Lessons from the Forest.

On the Eastern Shore of Maryland where she lives, a tract of mature forest was obtained by her county for conversion into a public park. For many residents and county officials, such a park meant ball fields, parking areas, and open spaces — not necessarily a forest. And then September 11th happened. In her grief, inspired by a talk on Buddhist approaches to nature, she decided to turn the forest grove into a memorial for the victims. With red yarn, she hung name tags of the fallen on trees, creating the September 11 Memorial Forest. The act at once established a sacred space for grieving, and protected the trees from being cut. Imagine another Memorial Day in Georgia, years from now. Families gather together, fill their picnic baskets, and wander off into the forest. They come at last to a sturdy beech, or sweet gum,

or sycamore, growing along the banks of a stream. At its base, a small stone bears the name of a brother, a husband, a son. Against a backdrop of birdsong and flowing water, they share memories of the love he had given, and tears, too, for the loss they have endured without him. All

around, they are consoled by the living presence of nature, in a forest forever protected as a memorial grove.

As Memorial Day approaches yet again, the naturalist’s thought turns to how we memorialize those our nation has lost in wars. We construct monuments of granite and marble, polished stone faces with lettering that has come to signify, in our culture, the tragic reality of death, of loss. Perhaps on Memorial Day we might visit a memorial, brush our fingertips against the cold stone letters, and touch, for a moment, our own inevitable mortality. Perhaps even while standing beneath an appropriately leaden sky, we weep for the enormity of our losses along the path to maintain the freedom we first fought for over two hundred years ago.

And while we weep, the chainsaws growl, and another tree falls in a stand of forest that stood untouched for the past fifty years or more. Bulldozers scrape their way across the land, and the forest is forgotten.

There is another way.

There is a way to honor our fallen and also to protect and cherish the living forests all around us. It is a model whose roots go back at least to ancient Greece, and probably further. The Greeks (and many other civilizations) maintained sacred groves, patches of forest where they could approach the great Mystery through ritual. The forest was a place for spiritual connection — an awareness not lost on Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon religion, who had a vision of God and Jesus while praying in a ten-acre beech grove on his family farm in 1820. As a result of this vision, that patch of forest is now cared for and protected. As Donald Enders writes in an article at www.LDS.org, “The Sacred Grove is one of the last surviving tracts of primeval forest in western New York state….. The Church has for some years been directing a program to safeguard and extend the life of this beautiful woodland that is sacred to Latter-day Saints.”

Along the streets of Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, and many other towns and cities across the United States, trees have been planted to honor the deceased. Beside the trees, small stone plaques bear a name, a few words of remembrance, and birth and death dates. Within this tradition, the idea of honoring the dead through caring for the living still remains. The next step back to the grove would be to recognize healthy, mature forests as being fitting sacred sites. Through dedication ceremonies and markers in the forest, they can become places to acknowledge our losses while celebrating life’s continuance, in leaves of an oak and flowers of a tulip poplar.

It is this very idea that Joan Maloof proposes in Teaching the Trees: Lessons from the Forest. On the Eastern Shore of Maryland where she lives, a tract of mature forest was obtained by her county for conversion into a public park. For many residents and county officials, such a park meant ball fields, parking areas, and open spaces — not necessarily a forest. And then September 11th happened. In her grief, inspired by a talk on Buddhist approaches to nature, she decided to turn the forest grove into a memorial for the victims. With red yarn, she hung name tags of the fallen on trees, creating the September 11 Memorial Forest. The act at once established a sacred space for grieving, and protected the trees from being cut.

Imagine another Memorial Day in Georgia, years from now. Families gather together, fill their picnic baskets, and wander off into the forest. They come at last to a sturdy beech, or sweet gum, or sycamore, growing along the banks of a stream. At its base, a small stone bears the name of a brother, a husband, a son. Against a backdrop of birdsong and flowing water, they share memories of the love he had given, and tears, too, for the loss they have endured without him. All around, they are consoled by the living presence of nature, in a forest forever protected as a memorial grove.