The utter nowhereness of that desert trail! Of its very start and finish! I had been used to starting from Hingham [Massachusetts] and arriving — and I am two whole miles from the station at that. Here at Mullein Hill I can see South, East, and North Weymouth, plain Weymouth, and Weymouth Heights, with Queen Anne’s Corner only a mile away; Hanover Four Corners, Assinippi, Egypt, Cohasset, and Nantasket are hardly five miles off; and Boston itself is but sixty minutes distant by automobile, Eastern time.

It is not so between Bend and Burns. Time and space are different concepts there. Here in Hingham you are never without the impression of somewhere. If you stop, you are in Hingham; if you go on you are in Cohasset, perhaps. You are somewhere always. But between Bend and Burns you are always in the sagebrush and right on the distant edge of time and space, which seems by contrast with Hingham the very middle of nowhere. Massachusetts time and space, and doubtless European time and space, as Kant and Schopenhauer maintained, are not world elements independent of myself, at all, but only a priori forms of perceiving. That will not do from Bend to Burns. They are independent things out there. You can whittle them and shovel them. They are sagebrush and sand, respectively. Nor do they function there as here in the East, determining, according to the metaphysicians, the sequence of conditions, and positions of objects toward each other; for the desert will not admit of it. The Vedanta well describes “the-thing-in-itself” between Bend and Burns in what it says of Brahman: that “it is not split by time and space and is free from all change.”

That, however, does not describe the journey; there was plenty of change in that, at the rate we went, and according to the exceeding great number of sagebushes we passed. It was all change; though all sage. We never really tarried by the side of any sagebush. It was impossible to do that and keep the car shying rhythmically — now on its two right wheels, now on its two left wheels — past the sagebush next ahead. Not the journey, I say; it is only the concept, the impression of the journey, that can be likened to Brahman. But that single, unmitigated impression of sage and sand, of nowhereness, was so entirely unlike all former impressions that I am glad I made the journey from Boston in order to go from Bend to Burns.

AT ITS BEST, “WHERE ROLLS THE OREGON” REVEALS THE REFLECTIONS OF AN EASTERN NATURALIST COMING TO GRIPS WITH THE ARID AND IMMENSE LANDSCAPES OF THE WEST. He is the archetypal Outsider, struggling to relate his experiences in the woodlands and fields of New England to the canyons, mountains, and empty country of Oregon. Here, Dallas Lore Sharp writes of his glimpse of a raven soaring over Deschutes Canyon, against a vast backdrop of emptiness and silence:

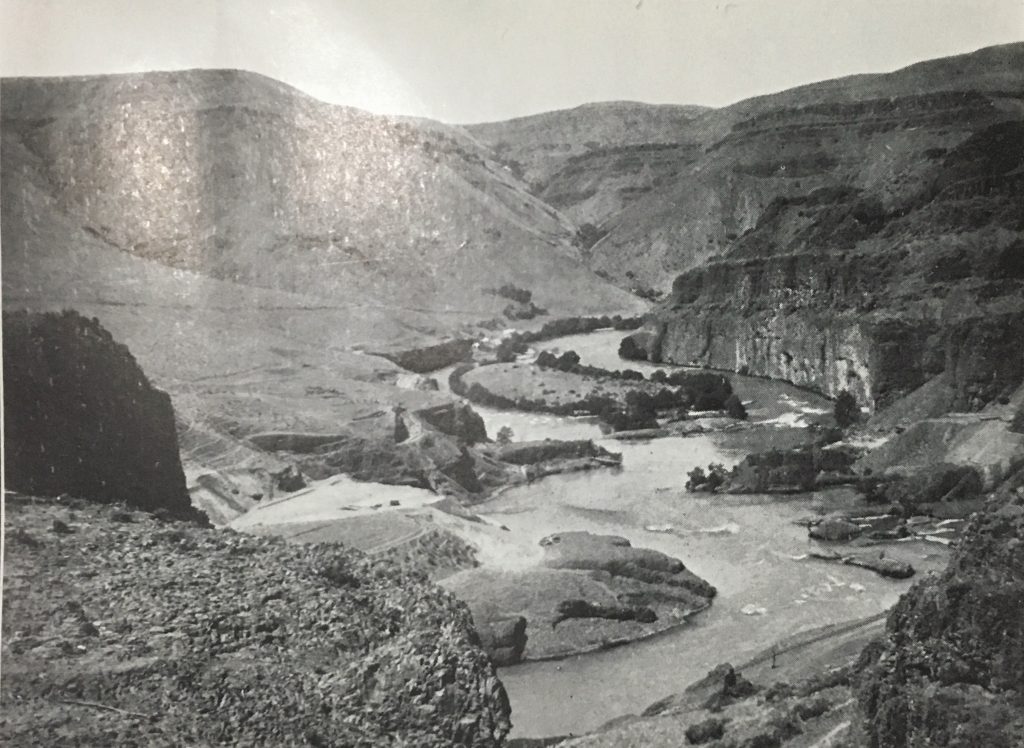

As our train clung to its narrow footing and crept slowly up the wild cañon of the Deschutes, I followed from the rear platform the windings of the milk-white river through its carved course, We had climbed along some sixty miles to where the folding walls were shearest and the towering treeless buttes rolled, fold upon fold, behinds us on the sky, when, of from one of the rim-rock ledges, far above, flapped a mere blot of a bird, black, and strong of wing, flying out into midair between the cliffs to watch us, and sailing back upon the ledge as we crawled round a jutting point in the wall and passed from his bight of the deep wild gorge.

…And I knew, though this was my first far-off sight of the bird, that I was watching a raven. Beside him on the ledge was a gray blur that I made out to be a nest — an ancient nest, I should say, from the stains below it on the face of the rock…..

Or did I imagine it all? This is a treeless country, green with grass, yet, as for animal life, an almost uninhabited country…. Such lack of wild life had seemed incredible; but no longer after entering the cañon of the Deschutes. A deep, unnatural silence filled the vast spaces between the beetling walls and smothered the roar of the rumbling train. The river, one of the best trout streams in the world, broke white and loud over a hundred stony shallows, but what wild creature, besides the osprey, was here to listen? The softly rounded buttes, towering above the river, and running back beyond the cliffs, were greenish gold against the sky, with what seemed clipped grass, like to some golf-links of the gods; but no creature of any kind moved over them. Bend after bend, mile after mile, and still no life, except a few small birds in the narrow willow edging where the river made some sandy cove. That was all — until out from his eyrie in the overhanging rim-rock flapped the raven.

FOR SHARP, THE WESTERN LANDSCAPE WAS FUNDAMENTALLY FOREIGN TO HIS EXPERIENCE. Spaces were so immense and so desolate and so unfamiliar to a New Englander. Not always able to appreciate the monumentality of the West, on at least this one occasion he gave up, turning his focus instead on a more familiar sight, reminiscent of what he might encounter back home:

How often one becomes the victim of one’s special interests! I climbed to the peak of Hood, looked down upon Oregon and into her neighbor states, saw Shasta far off to the south, and Rainier far off to the north, and then descended, thinking and wondering more about a flock of little butterflies that were wavering about the summit than about the overpowering panorama of river and plain and mountain-range that had been spread so far beneath me. Or was I the victim, rather, of my inheritance? Was it because I happened to be born, not on a mountain-peak eleven thousand two hundred and twenty-five feet above the sea, but in a sandy field at sea-level? I was born in a field bordering a meadow whose grasses ran soon into sedges and then into the reeds of a river that flowed into the bay; and I found myself on the summit of Hood dazed and almost incapable of great emotion. So I watched the butterflies.

THIS BOOK HAD BEEN A RARE FIND FOR ME: a natural history study of the Pacific Northwest, written between 1862 and 1942. And several of its essays, particularly the ones quoted above, lived up to the expectation. But after reading Enos Mills’ accounts of his adventures in the Rockies, I also came to recognize that there is a considerable difference between the West as portrayed by a deep inhabitant of its wilds, and the West as encountered by an Eastern nature rambler visiting for a couple of months one summer. That difference continues to fascinate me. Alas, however, the book as a whole is highly uneven and its structure rather baffling. It opens with a visit to the seabird-covered crags of Three-Arch Rocks Reservation, just offshore west of Portland. The next section of the book is the most coherent, covering Sharp’s time in eastern Oregon, including the epic drive from Bend to Burns. He visits desert wetlands filled with birds (except for the white heron, driven nearly extinct at the time by the brutal millinery trade). Then he inserts a lengthy consideration of herd behavior, which begins with cows in the pastures of Hingham and ends with a cattle stampede in eastern Oregon. After the butterflies of Mt. Hood he shares about his encounter with a cony (pica) in the Wallowa Mountains. Then back to Shag Rock in Three Arch Rocks Reservation (on the same visit as began the book), then a long essay on animal mothers that again started in New England and ended back on Three Arch Rocks again. Then a final appreciation of Mt. Hood as seen from Portland (with some ponderings on Portland’s economic and cultural potential. And then the book closed.

THE FINAL RESULT IS A SERIES OF VIGNETTES, SNAPSHOTS FROM A PLEASANT RAMBLE THROUGH THE WESTERN WILDS. To his credit, Sharp advertises it as such in the Preface, where he explains that “…this volume is…a group of impressions, deep, indelible impressions of the vast outdoors of Oregon. Still, the reader is left longing he would develop his impressions of the West into a more coherent, richer, more extensive volume. The editor, too, might have encouraged him to save essays on animal behavior (mothering and herd instincts) for another book, and instead to concentrate on encounters with the Western landscape and its flora and fauna. Finally, most ironically of all, Sharp’s title, “Where Rolls the Oregon” (lifted from Thanatopsis, a poem by William Cullen Bryant) refers to an older name for the Columbia River, whose striking gorge along the Oregon/Washington border cuts through the heart of the Pacific Northwest. Yet Sharp does not mention the river even once in his book.

I WAS FORTUNATE TO LOCATE A VOLUME IN SUPERB CONDITION. It is a first edition from 1914, with cover art well preserved. It was signed by a previous owner, Henrietta A. Pratt, but without a date. My attempts to track down the owner via Google met with no success. At very least, I would like to thank her for caring for this book so thoughtfully.

Thank you.

You are very welcome, Elizabeth!