In “Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes” I made note of intimate studies of such regions in my sojourns at Ipswich, of the varied forms and movements of the sand, of the growth and origin of the salt marsh and of the life in the dunes and the marshes both animal and vegetable. In the following pages I have endeavored to set forth additional studies in these same regions.

I have called the present volume by the title of “Beach Grass”, partly because this grass is so characteristic of the region and partly because of the meaning of its scientific name — Ammophila arenaria — the sandy sand-lover.

I am on a streak of two now. Again I have selected a book whose single greatest asset is its cover. I do not speak ill of the book’s contents, really — the cover, yet again, is quite visually appealing. The book as a whole simply never achieves greatness. But then again, Towsend warns readers from the beginning that he is effectively publishing an addendum to his earlier volume (previously reviewed). While Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes was intended to cover, in turn, the various landscape types of the Ipswich coast, this book feels instead like a smattering of additional bits — bonus material to what came before. Several times in the book, Townsend refers readers back to his first volume. Here, he builds on what came before, with more (and better) photographs of dunes and dune tracks, and an extensive section of several chapters on winter conditions along the coast. Then there is a section on a small forest that Townsend planted on his coastal property, and the lean-to he constructed within it. I cannot help but think of the cabin at Walden, though Townsend leaves the philosophizing to others in favor of straightforward accounts of his observations. At one point in a later chapter (“Hawking” — observing hawks, not hunting with them), Townsend even dares a dig at Thoreau:

It is true that one’s aesthetic sense may be gratified and one may receive great enjoyment from birds and flowers without knowledge of their structure or names. But on the other hand it is not true that a study of structure and the recognition of the species in the field is a detriment to the pure enjoyment of these wonderful creatures of nature. The musician who understands the musical composition of a symphony and whose ear is attuned to all its finer points, receives at a concert infinitely more pleasure than one who is ignorant of these matters. One who has studied flowers and birds and is able to distinguish the exact kind and the significance of form and markings, sees far more of their beauty than one not so trained and he obtains correspondingly more enjoyment. The untrained observer often fails to see the bird or flower at all, and if it is called to his attention, sees it but imperfectly. The enjoyment shown by naturalists — and I refer to the out-of-doors and not to the closet type — is evidenced in their writings. Wilson, Audubon, Darwin and Wallace, Gilbert White and Hudson are conspicuous examples. I am sure, although it is heresy to say so, Thoreau would have had more pleasure from his studies of out-of-doors and would have given the world more pleasure, if he had been willing to study more closely and identify more carefully birds and flowers.

Zing. OK, another reason this book doesn’t quite leave me enraptured.

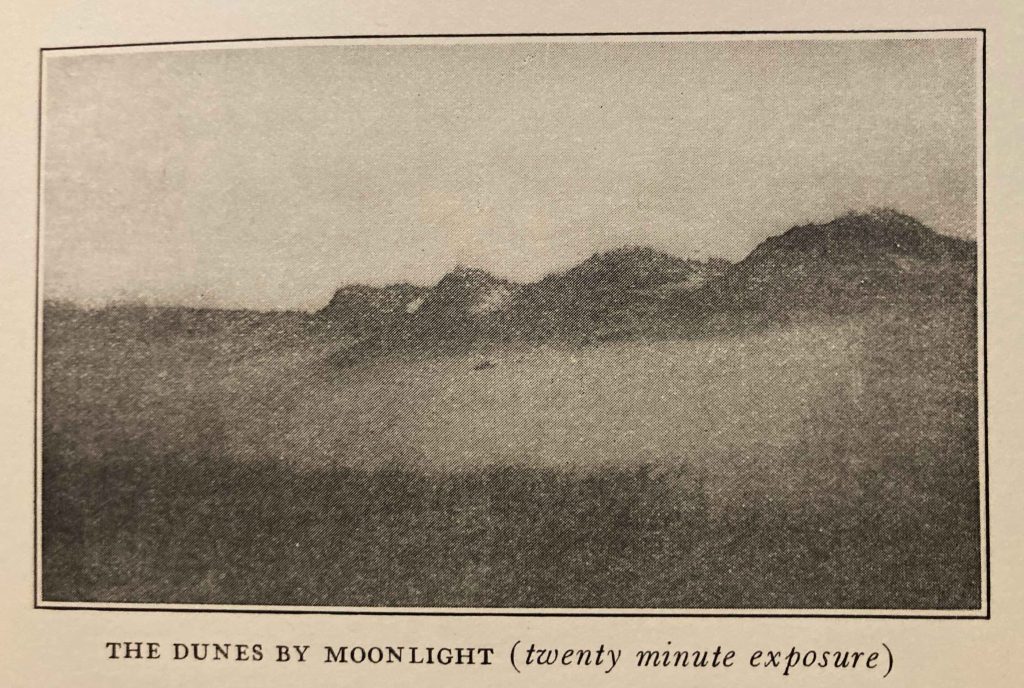

Speaking of rapture, though, Townsend took a particular fascination for the ever-shifting coastal dunes. Here he describes two nighttime encounters with them — first at the full moon, and again during the autumn bird migrations:

At the time of the full moon the fascination of the sand dunes is increased to a superlative degree. The whiteness of the sand augments the brilliancy of the moonlight, just as is the case when the landscape is white with snow. Such a night was that of September 25 and 26, 1920. It was calm and warm, 68° Farenheit by the cricket thermometer. As I wandered alone about the dunes, listening to the voices of the birds passing overhead, and of those on the shore and sea, I was alert for a glimpse of night-wandering animals whose tracks were clearly visible by moonlight. Exposing a photographic plate for twenty minutes to the mysterious scene, I patiently waited and watched during this interval but saw no track-maker. The sky on the sandy horizon — on the crest of a sand wave — looked black in comparison with the white sand, but this starless darkness soon merged into the vault of the heavens with its suggestion of blue, studded sparsely with stars. Only those of greater magnitude showed in the brilliant light of the moon; the light of the lesser ones was quenched. We pay for the light of the full moon by loss of starlight just as we pay for sunshine by loss of moonlight. About five in the morning the moon set large and red, and the lesser as well as the greater stars blazed out, and the path of the Milky Way appeared across the heavens.

After a period of unfavorable wind or weather, a perfect night may come when the floodgates of bird migration are opened, and the pent-up multitudes, waiting for this chance, pour along the aerial channels. Such a night followed September 9, 1916, and it was my good fortune to spend it in the dunes and on the beach. The air, blown as clear as crystal by a sparkling northwest wind, and illuminated by the full moon, and its reflection from the sea and white sand, made the night almost as light as day. There was a brilliancy and ethereal quality suggestive of fairyland. Such nights as these fill one with rapture at the marvelous beauty and mystery of the sand dunes.

Here is another somewhat poetic passage from yet another night he spent among the dunes, interspersed with a couple of lines of poetry from William Wordsworth:

At night there is a gentle mystery and a sense of primeval grandeur in the sand dunes that sur- passes the mystery and the grandeur of the day. It is good for the soul to escape from the conven- tionalities of life and lose itself in darkness in this waste of sand. Like a wolf, turning and shaping his form in the grass before he lies down, so the dune-lover shapes his form in the sand, hollowing places for his shoulders and hips. Lying thus in his mold, securely wrapt in his blanket, on the crest of a dune wave, he sees the sun set, the blue eclipse of the sky by the earth rise in the East, and the pink glow overhead and in the West gradually fade. Swallows in straggling bands and in great multitudes, hastening to their night roost, skim close by, sometimes within a hair’s breadth of his face. The dark, ungraceful forms of night herons pass over with slow wing-flaps and discordant croaks, and the stars come out until the whole vault of heaven is aglow. Those who dwell in caves, in deep canyons or in rooms in city streets, know not the brilliancy of the heavens as revealed to those who lie out under the stars. They know not:

”The silence that is in the starry sky. The sleep that is among the lonely hills.”

The laughing cry of the loon comes to his ears from the sea and the noisy clamor of a great company of herring gulls, gossiping with each other as they settle down for a night on the shore. Sandpipers and plovers whistle as they fly over, and the lisping notes of warblers, mi- grating from the sterile cold of the North, drop from above. Forming a continuous background to these voices is the boom and the crash of the waves on the sea beach.

For the sake of full disclosure, Townsend also shares a couple of nights among the dunes that did not pass so beautifully, thanks to the ravages of sandblasting winds and numerous vicious mosquitoes.

While Townsend’s first volume was published in 1913, this one is a decade later, with the Great War between them. In a couple of places here, memories of the war appear, offering hints of how many ravages it had wrought and how much it lingered in the American consciousness. Describing the impacts of a severe ice storm on the trees, he writes of a white maple whose “soft and brittle wood was unable to bear the heavy load of ice, and the snow underneath was covered with branches and great limbs torn and splintered as if the trees had been through a German barrage.” A few pages later, he describes experiencing the Northern lights as a patriotic vision:

Although the aurora borealis is not limited to the winter season, it is displayed to greatest perfection at that time. One of the most beautiful auroras I have ever seen occurred one cold clear night in March, 1918, during the Great War, and the superstitious might well have read omens in its display. A series of white streamers radiated from the zenith, constantly waving and changing their places. Whole sections of the sky glowed a blood red, as if it reflected a mighty conflagration or a mighty slaughter, and the snow was tinged with the crimson flood. When this crimson sky was crossed with bars of white with here and there patches of dark blue, it needed little imagination to picture a draping of the sky with Old Glory.

Finally, I cannot help but include in this highly scattered review some mention of a passage that suggests that concern over climate change — specifically, warming — actually dates back a full century. Ironically, Townsend argues firmly that the climate is unchanging (using quite valid scientific arguments to make his case):

Severe winters are sure to recur either singly or in a series and they are apt to shake the faith, temporarily at least, of those who say the climate is changing and is much milder than when they were young. Then, according to these wise ones, snow came regularly at Thanksgiving and there was sleighing until the end of March. Meteorological records kept for many years show that mild winters and severe winters occurred a generation ago as they do today, and that the snowfall has varied irregularly…

…in the long run, the cold and warm, the dry and wet balance each other, and the general average is the same. Meteorologists believe that there has been no material change in the climate within historical times.

Yet it is a common idea that the climate of New England is growing milder, and when we have much cold and snow, the older people speak of it as an ”old-fashioned winter.” The human mind is prone to remember vividly and even to magnify unusual events and seasons, while ordinary seasons of snowfall are forgotten. Then, too, a snowdrift three feet high, struggled through by a child, assumes gigantic proportions in the memory when the child has reached mature age and size.

In our cities a generation ago, the snowfall was not managed as efficiently as it is now, when powerful snow ploughs and gangs of men clear the streets within a few hours of the storm. In former days the snow was allowed to accumulate and remained longer in the way of traffic. Another cause for self-deception exists with those who have spent their earlier years in inland towns or country where the snowfall is greater and comes earlier than it does in coastal regions. A very few miles often makes a considerable difference.

While the Industrial Revolution marked the beginnings of the increase in carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, 1923 was far too early for meteorologists to detect a warming signal. Still, it is intriguing that some people were convinced otherwise back then.

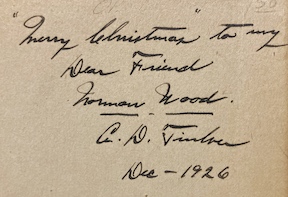

My copy of this book is marked by a holiday dedication from C. D. Tinker to his/her dear friend, Norman Wood, in December of 1926. Unfortunately, without a first name, C. D. Tinker is impossible to track down online, and the same is the case for Norman Wood, whose name is too commonplace — I simply cannot see the Wood for the Woods. I do hope Norman enjoyed this book.