I find the night, like the cup of Comus, “mixed with many murmurs.” First and the nearest at hand, the lively orchestration of the crickets (the later summer adds the fife of a grasshopper and the castanets of the katydid); then, in the distance, the regular, sonorous, or snoring antiphonies of the frogs at different points along the winding course of the creek. It would not surprise me to learn that these night musicians are systematically governed by the baton and metronome, so well do they keep time in the perplexing fugue movement which they are performing.

THANK GOODNESS FOR WIKIPEDIA, OR ELSE EDITH THOMAS WOULD HAVE LOST ME ON HER VERY FIRST LINE. Comus, it turns out, was the Greek god of festivities and revels. A god of excess, he represents anarchy and chaos. He was cup-bearer for Dionysus, Greek god of wine and fertility, so it is fairly easy to guess what Comus’ cup contained. Knowing this adds a contextual richness to Thomas’ imagery; the sense of chaos and wildness is juxtaposed with the “orchestration” of the “night musicians”. I glimpse a poet at work here.

EDITH THOMAS WAS FIRST AND FOREMOST A POET, FAMOUS IN HER DAY AND COMPLETELY FORGOTTEN NOW. Her poetry is tightly constructed, flowery, and ornate. Fortunately for her, and we in the 21st century, she also wrote a single book of nature essays, “The Round Year”, published in 1886. Written shortly after Thomas moved from her native northern Ohio to New York City (where she remained the rest of her life), the book is infused with a bittersweet longing for her home place. (“Who knows whether soul or body pines more for the familiar environment?” she asks in the book’s first essay. “Have wood, field, rock, and stream vested in us something of theirs? Or have we parted our spirit among them, that separation touches us so sorely?”) The title of her book comes from a poem by Emerson with these lines, “Cleave to thine acre; the round year / will fetch all fruits and virtues here.” In this, my third book journey, the pendulum has swung a full arc, from a scientist who seasoned her careful observations with a few poetic passages (Mary Treat) to a poetic rambler with a keen eye for birds and trees (Bradford Torrey) to a dedicated lifelong poet, well versed in literature and Greco-Roman mythology.

IT IS EASY SOMETIMES TO DROWN IN THOMAS’ LITERARY ALLUSIONS, WONDERING AT THE POINT OF IT ALL. There are certainly obstacles to accessing her work. By this, I mean not only the mythological thickets abounding in her prose but also her poetic flights of fancy that sometimes left me wondering if it all might be condensed to a pithy sentence or two instead. It is easy to write her off as lost in raptures of poetic fancy and musings of obscure myth, disconnected from nature. And then the minute I decide that, I find a passage that convinces me that she is, in fact, a perceptive observer of the natural world:

A strange servitude is this of the oak to the cynips, or gall-fly, in thus contributing of his substance to the housing and nourishment of his enemy’s offspring. The mischievous sylph selects sometimes the vein of a leaf, sometimes a stem, which she stings, depositing a minute egg in the wounded tissues. As soon, at least, as the egg hatches, the gall begins to form about the larva, simulating a fruity thriftiness, remaining green through the summer, but assuming at length the russet of autumn. The innocent acorn nature puts to bed as early as possible, that it may make a healthy, wealthy, and wise beginning on a spring morning; but the cradle that holds the gall-fly’s child she carelessly rocks above ground all winter.

THERE IS SCIENTIFIC ACCURACY HERE, THOUGH CLOTHED IN POETIC TRAPPINGS. Replace the sylph — an imaginary aerial spirit — with a wasp, and you have a fairly robust description of the formation of an oak gall. And sometimes Thomas’ poetic insights can even shift from being an obstacle to understanding to offering the reader a path toward an alternative way of encountering the world, a reminder that a successful scientist needs imagination and wonder, too. Consider this image:

Would you for a while shut out the earth and fill your eye with the heavens, lie down, some summer day, on the great mother’s lap., with a soft grass pillow under your head; then look around and above you, and see how slight, apparently, is your terrestrial environment, how foreshortened has become the foreground — only a few nodding bents of blossomed grass, a spray of clover with a bumble-bee probing for honey, and in the distance, perhaps the billowy outline of the diminished woods. What else you see is the blue of heaven illimitably stretched above and beyond you. You seem to by lying not so much on the surface of earth as at the bottom of the sky.

Consider, too, this lovely blending of mathematics and flowing water:

In cooler and deeper retirement, on languid summer afternoons, this flowing philosopher sometimes geometrizes. It is always of circles — circles intersecting, tangent, or inclusive. A fish darting to the surface affords the central starting-point of a circle whose radius and circumference are incalculable, since the eye fails to detect where it fades into nothingness. Multiplied intersections there may be, but without one curve marring the smooth expansion of another. There are hints of infinity to be gathered from this transient water-ring, as well as from the orb of the horizon at sea.

DESPITE THEIR DIFFERENCES IN WRITTEN VOICE, TREAT AND THOMAS SHARED MUCH COMMON GROUND. For instance, just as Treat studied nature in the field (the backyard or the further woods), so Thomas spoke strongly of the need to engage with living nature, instead of collecting dead specimens. On the very first page of “The Round Year”, for instance, she addressed the reader thus:

You come, eager and aggressive, on your specialist’s errand, whatever it may be — botany, ornithology, or other; you may take hence, perforce, a large number and variety of specimens, press the flower, embalm the bird; but a “dry garden” and a case of still-life are poor showings for the true natural history of flower or bird.

ANOTHER COMMON ELEMENT IS THAT BOTH WRITERS ENCOUNTERED A KINGFISHER AND DESCRIBED IT TO THE READER. A comparison of the two accounts provides further insight into their different approaches to observing birds. First, Mary Treat:

The belted kingfisher (Ceryle alycyon) is another familiar bird that frequents the grounds. His name indicates his occupation, and a very successful fisher he is. His fishing-post is on the railing that runs along the wharf. The wharf extends from the grounds about two hundred and fifty feet into the river. Whether he remains at this post the entire year I do not know; we find him here upon our arrival, and leave him here when we depart for the North. I am inclined to think that his permanent residence; at all events, he objects to being disturbed, as if he had been sole manager too long to yield the ground without a loud protest. If more than one person geos upon the wharf, he leaves with a clang and clatter which sound like a watchman’s rattle. and usually flies to the terrace, and alights upon a small tree bending over the water, where he can overlook and watch proceedings. But he does not seem to be afraid of one person alone; if I go upon the wharf unaccompanied, he flits along before me, alighting upon the railing, often not more than fifteen or twenty feet distant, and faces about as if to intimidate me. Seeing this I quietly drop upon a seat; for really, with his rumpled crest and fierce-looking black eyes, he looks rather formidable, being a foot or more in length. Seeming to be satisfied that I am under subjection, he goes on with his fishing, in which he is very expert. Motionless he eyes the finny tribes beneath him until one of their number comes within his range to suit his taste, when he dives under the water and brings it up; and now beating it upon the railing until it is quite limp, he swallows it. Small fish-scales are scattered along the entire length of the railing, where he has dressed his fish preparatory to taking his meals.

And now a very different account of a kingfisher (likely a different species, one found along Lake Erie in Ohio) from the pen of Edith Thomas:

There were fish taken under my observation, though not by line or net. I did not fish, yet I felt warranted in sharing the triumphs of the sport when, for the space of ten minutes or more, I had maintained most cautious silence, while that accomplished angler, the kingfisher, perches on a stately elm branch over the water, was patiently waiting the chance of an eligible haul. I had, meanwhile, a good opportunity for observing this to me wholly wild and unrelated adventurous bird. Its great head and mobile crest, like a helmet of feathers, its dark blue glossy coat and white neck-cloth, make it a sufficiently striking individual anywhere. No wonder the kingfisher is specially honored by poetic legend. I must admit that whenever I chanced to see this bird about the stream it was faultless, halcyon weather.

IT IS AMAZING TO THINK THAT BOTH AUTHORS ARE ENCOUNTERING THE SAME BIRD. I have to confess that Treat’s kingfisher strikes me as far more believable than Thomas’s. Perhaps that is in part because Treat sought to interact with the kingfisher, while Thomas instead watched it quietly from a distance. Treat’s kingfisher emerges as a unique character, while Thomas’s is inextricably part of a semi-mythical landscape, with one foot on an elm branch and the other lost in the mists of “poetic legend”.

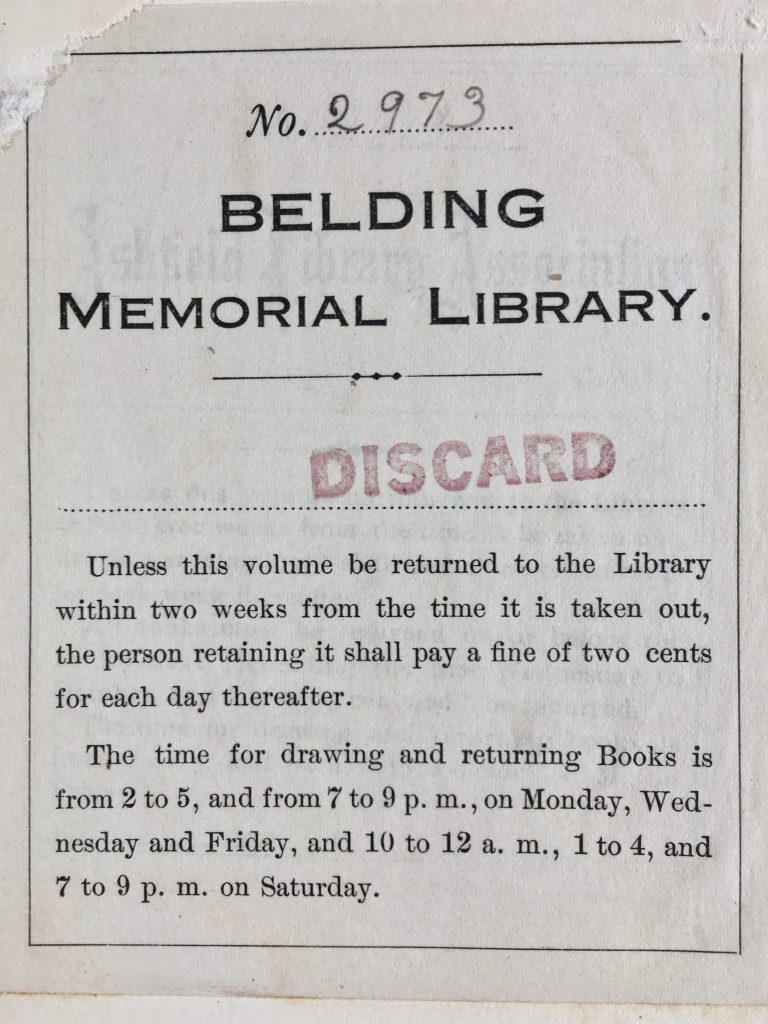

AS A POSTSCRIPT, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY PARTICULAR VOLUME. I managed to locate an 1886 copy, the first (and, I suspect, only) edition. It is an austere volume, bound in army gray without ornamentation apart from the title and author in gold on the spine. It was once Number 2973 at Belding Memorial Library but was stamped Discard at some point. Curious about where my book had been, I tracked down the library. There are two Belding Libraries. There is one in Michigan, but I do not think that is the correct one, since that is technically the Alvah N. Belding Library (in Belding, Michigan). More likely, this book was once held by the Belding Memorial Library in Ashfield, Massachusetts, pictured below.