There is a nameless charm in the flatwoods, there is enchantment for the real love of nature in their very sameness. One feels a sense of their infinity as the forest stretches away into space beyond the limits of vision; they convey to the mind a feeling of boundless freedom. The soft, brilliant sunshine filters down through the needle-like leaves and falls in patches on the flower-covered floor; there is a low, humming sound, sometimes mimicking the patter of raindrops, as the warm southeast wind drifts through the trees; even the loneliness has an attraction. To me it all brings a spirit of peace, a feeling of contentment; within the forest nature rules supreme. The memory of all that is evil and annoying has fallen away like the burden of Christian at the foot of the cross; I am alone and utterly care free in the pine woods. I cast off all my troubles and discomforts of my daily existence, the strain and worry of civilization; I am happy as a child. I am at peace with the earth, the forest, the sky, the entire world. As I lie in the long, soft grass I feel that I do not care to go back to the dull, sordid routine of every day life again.

GOING BACK THROUGH THIS BOOK AFTER RELUCTANTLY FINISHING IT, I KNEW RIGHT AWAY WHAT PASSAGE TO CHOOSE TO OPEN MY POST. No matter that Simpson was in his mid-70s when he wrote this book (he lived nearly another decade after this) — his childlike nature is everywhere on these pages. Wandering the Florida Keys, he gleefully recalls all the times he was mistaken for a tramp and (literally) left out in the rain by residents who looked askance at him. In pursuit of his beloved tree snails, he nearly died from mosquito bites (more to follow on that) and was constantly in the mud or struggling through greenbriars and thorny cacti. Yet he was also a keen scientist, one who used his tree snail collection to assemble a history of the environmental changes South Florida had undergone in the previous thousands of years. His writing is a delight, albeit a costly one (more about that later, also). He speaks of nature with religious rapture on one page, then recounts tales of Cuban rum-runners he knew that managed to evade the law by various creative means. I will save the humor and pathos of his collecting adventures for the second half of this post; first, though, some more passages that place him firmly in the company of religious naturalists. This one is from an account of a visit to Paradise Key in the Everglades:

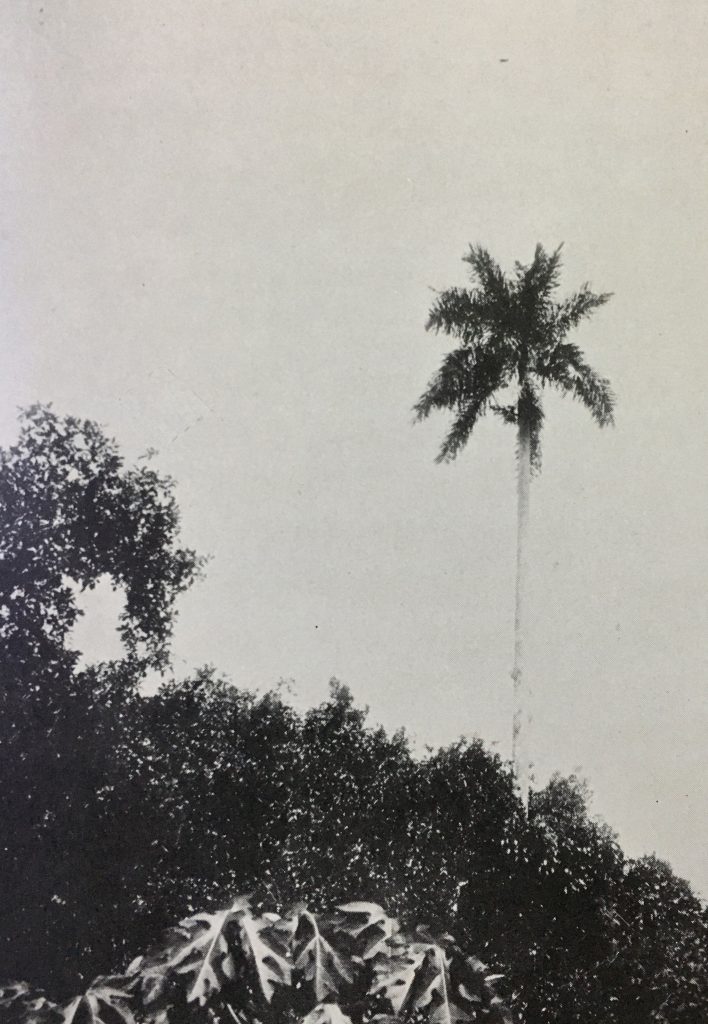

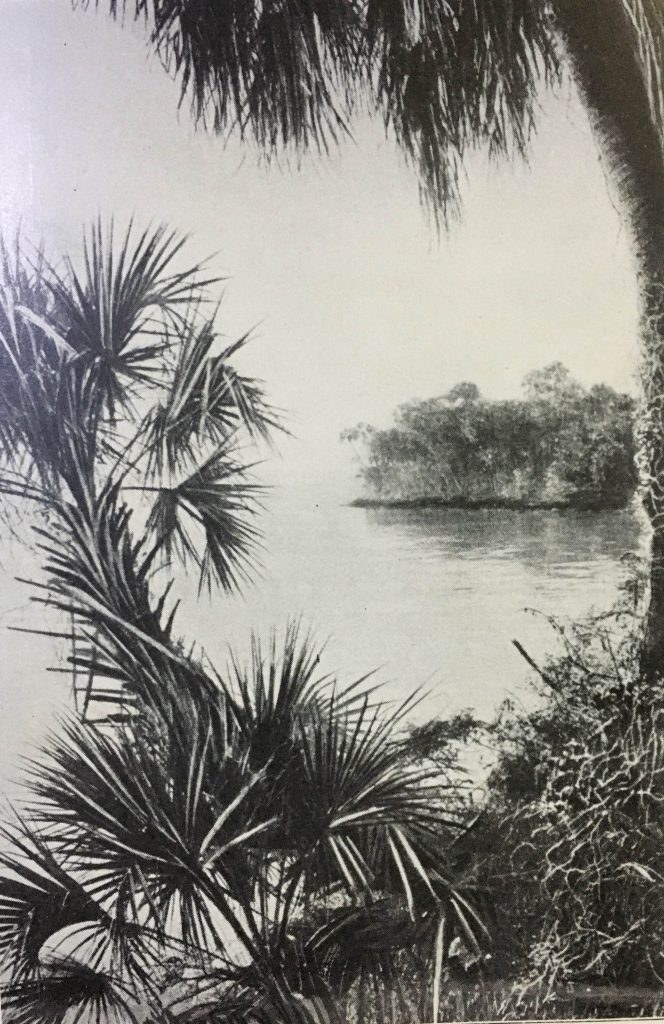

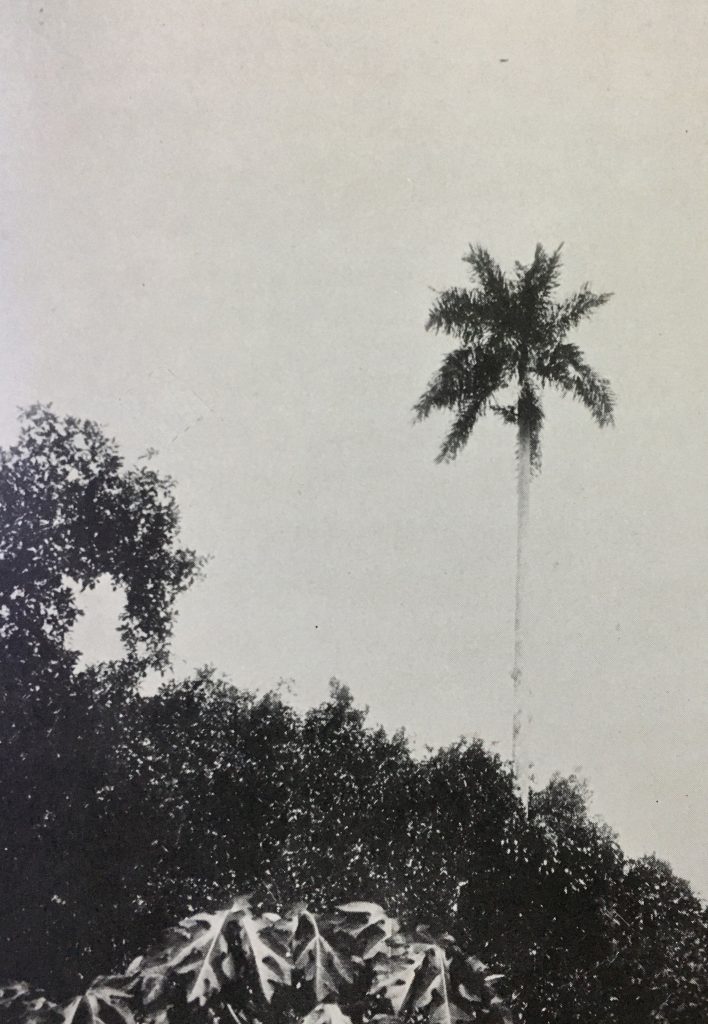

We ventured a little way into the glades but the rains had made the mud very soft and after getting a backward view of the forest in which some fifteen great royals [royal palms] showed themselves, we started in on our return along the trail. Before reaching the road I left my companions and went back into the hammock. Leaving the trail I worked my way out into the dense, tangled growth, and as I sat down at the foot of a great tree and gazed around and upward it seemed as though the spirit of the forest took possession of me. On the ground was a carpet of dead leaves, for in such places they are falling all the time, and over this the few rays of the sun that came through the dense foliage seemed to be almost filtered. Near me several young palms, twelve to fifteen feet high, stood like graceful forest nymphs, their long leaves arching upward and outward with indescribable beauty. Around me on every hand were countless trunks of other trees varying from a few inches to several feet in diameter, erect, leaning or nearly prostrate, those of the live oaks almost black from the wetting by the rain, the gumbo limbos coppery, the poison tree brown, the West Indian cherry reticulated and variegated while the lancewoods and Ilex were white. Some were clothed with vivid green from several feet from the ground, a mantle spread over them by the abundant mosses, and immense lianes were carelessly thrown over all. Close by was the smooth, straight trunk of a big royal, pushed far up, its crown lost in the greenery above, but not far away stood another and through an opening in the leaves I could see its great head restlessly swinging in the strong wind, not a breath of which reached the ground where I sat. Not the slightest sound disturbed me; in fact one of the charms of the great forest is its stillness. I sat and fairly drank in the wonderful silence and loneliness of the hammock. In such a place one must be alone to enjoy the full beauty and sweetness of it all. Even the presence of the most congenial friend or lover of nature is distracting and in a sense a disturbing element. Alone with uncovered head I bared my life, my all to the Great Power of the Universe, call it Nature, God, Jehovah, Allah, Brahma or whatever you will, and reverently worshipped.

In his very next essay, The Vagaries of Vegetation, he shares his thoughts about intelligence in nature, coming to a conclusion as to where his religious outlook lies:

There is no chance, no haphazard; nothing happens. The universe is governed by law; no power can change or set it aside for a moment. Whenever and wherever life can fit itself to its domination it will survive and flourish; if it does not it perishes and becomes extinct.

I cannot believe either in a loving or hating deity who sits on a throne somewhere in the universe and watches over his creatures, who listens to and answers prayers, who orders the suns and planets on their courses, who make the rains , the wind storms and earthquakes. Yet I cannot be a mere materialist. I am sure there is not only matter and law but that there is intelligence, spirit. I constantly find the lower forms of life doing just what I would do with their environment, sometimes with less intelligence, sometimes with more. I can only believe that in a way these things think. I believe I must be, to some extent, a Pantheist.

LEST WE CONSIGN SIMPSON TOO QUICKLY TO THE ROLE OF MOUNTAINTOP (OR TREETOP) SAGE, THERE IS ANOTHER, HIGHLY COMICAL AND SELF-DEPRECATING SIDE TO HIM WHICH I ENJOYED IMMENSELY. His first essay in the book, Down the West Coast, chronicles an 1885 boat trip along the southwest coast of Florida that kindled his zoological cravings:

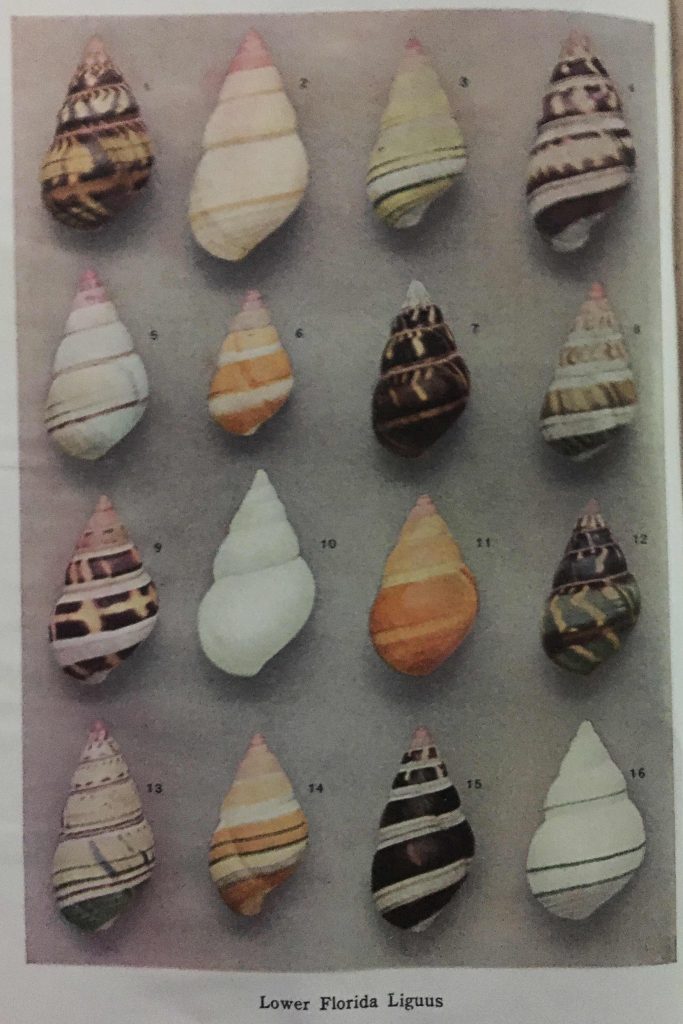

Not very far away [from the ruin of a coastal home] there was some fine hammock and on searching through it I came across the first specimens of the large, handsome arboreal snails called Liguus I ever collected. I was overjoyed to find them and from that day to the present time I have been completely daft about them, having tramped and traveled thousands of miles in lower Florida, Cuba and Haiti in an effort to collect and study them.

These wanderings led to some challenging moments for our author-protagonist, to say the least. Lest the reader every contemplate a trip to the Florida Keys, here is Simpson’s tale of his quest for Liguus specimens on Lower Matecumbe Key, long before the highway 1A was built (though after the Keys were connected by railroad):

The island of Lower Matecumbe is about three miles long and shaped something like a kidney with the concave side toward the mainland. The southwest end is largely a buttonwood swamp, but the other end is higher and contains a good deal of very dense, gangled scrub hammock. There are probably sixty or more species of native trees on the island, all tropical unless it is the cabbage palmetto, and the forest nowhere rises to a height of over thirty-five feet. A large part of the trees and vines are thorny, and I counted a full dozen species of these as I worked by way into it, twelve apostles of villainy, the worst of all being the dreadful Cereus pentagonus [triangle cactus]. There were three other cacti, the terrible pull-and-haul-back, a toothache tree, a Pithecolobium which bears the appropriate common name of “cat’s claw”, a couple of rampant vines, (Guilandina or nicker beans) which are covered with spines even to the seed pods, tw hateful Smilax [green briar] and a dwarf century plant. In such scrub the rocky floor is more or less covered with decaying tinder and as one of the natives once observed, “Them thorns stays right thar an’ is ready for bizness after the wood is all rotted an’ gone.”

In places the forest was so dense I had t get down and crawl and in others I was obliged to turn back and get out at the spot where I entered. I have seen mosquitoes worse, but not very often, and it seemed to me that most of the space not occupied by them was filled with sand flies, though there was sufficient room left for all to work freely. Between them they kept my hands and face covered, the bit of the latter feeling like the burn of a coal of fire. Though outside the hammock the wind was strong not a breath was felt where I worked and I was literally in a sweat bath. Every small tree and shrub I touched threw down a shower of water on me and my shoes were soon full. However, it was an ideal time for my business for snails are very active during wet weather, though they hid away when it is dry….

Before I had been in five minutes I ran into one of the curious wasps’ nests which are common in Lower Florida. They are hung to a twig by a slender stem and consist of a single series, or sometimes two, of papery cells whose sides are so glued to each other that they run diagonally to the direction of the whole. The wasps are small but make up in ferocity what they lack in size; they are regular dynamos of condensed villainy. A little later I ran into another and shortly before leaving the hammock I stumbled and partly fell, striking my hand against a third. In attempting to run from the wasps I stepped into a depression and fell full length into a bed of the dreadful cactus (Cereus pentagonus). Finally my face swelled so from the stings that I could scarcely see, and I determined to leave the hammock. On account of the cloudiness I could not tell which direction to take, but fortunately a train came along and I was soon out on the right of way. In climbing up the embankment I stumbled and fell, dropping my little sack and stepping on it. When I got to the track and turned out the contents I found every precious shell crushed to atmos. I was not merely angry, I was furious. I said that any man, especially at my age, who would come to such an inferno to collect was an idiot. I declared that I would at once go back to camp, pack up and flag the first train for home, that I would never come to the Florida Keys again. After tramping a quarter of a mile the strong wind and rain which blew in my face cooled alike my temper and temperature. I began to think that one of the chief objects of my coming to the Keys was to visit this island and work out certain important problems in distribution and evolution, that if I went home without doing this my trip would be largely wasted and that I might never come again. Why should I be so foolish as to be driven out by a few hardships? Then I wavered, stopped, turned back and went into the inferno again.

But it was on another trip, this time to Big Pine Key, where Simpson nearly died from all the mosquitoes attacking him:

Between the heel or point of Big Pine where the railroad coming from the north enters and the main island is a strip of swamp about two miles long. Over this the track was grown up thickly with grass and weeds to a height of a foot or so and in this the mosquitoes were packed almost solid. Although the atmosphere was full of them yet as I walked along I stirred them up by uncounted millions. The swarms were so dense at times that when I looked downward I could not distinguish the tracks or vegetation, nothing but a confused brownish green cloud and above they dimmed the light of the sun, they actually darkened the air. I have had a good deal of experience with mosquitoes…but I believe I can honestly say that fr numbers and fierceness as well as for a long continued siege what I saw and endured that day exceeded anything I have ever known before or since. I constantly broke off branches from the scrub along the road and brushed them off as well as I could, but they covered the exposed parts of my body until they were gray, and whenever I wiped them from my face, neck or hands the blood dripped on the ground.

The effect of the stings of such a swarm soon became something like that of morphine, producing a stupid, drowsy sensation, and in addition to this my cheeks and eyelids swelled until it was difficult to see. I began to grow weak, my legs tottered, and I realized that I could only last a limited time. Things swayed around me as if I was on a rolling vessel, and again and again I said: “Can I ever get through?” Twice I went to the side of the track and dropped down and gave up, but had I remained there I would have been dead in ten minutes. As often by a supreme effort I dragged myself on to my feet and staggered on half out of my mind for what seemed like hours. Finally I reached the main part of the island and realized that my tormenters were becoming less numerous. I passed through the village and on to where I was stopping, but could not eat and sleep and was sick all night.

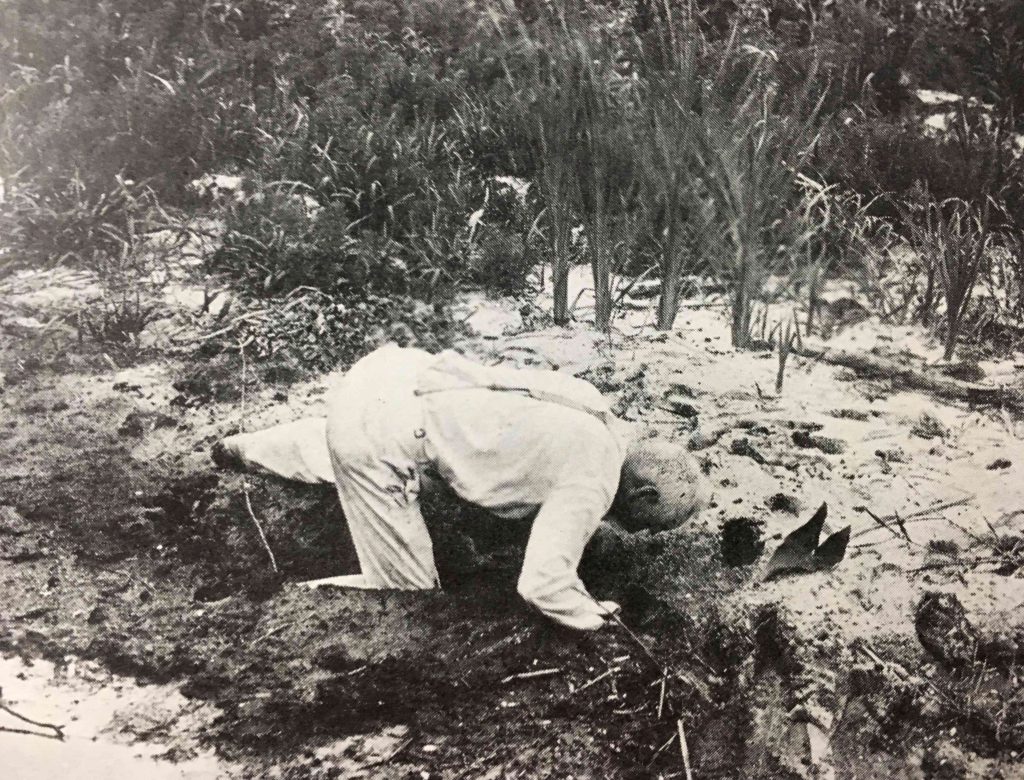

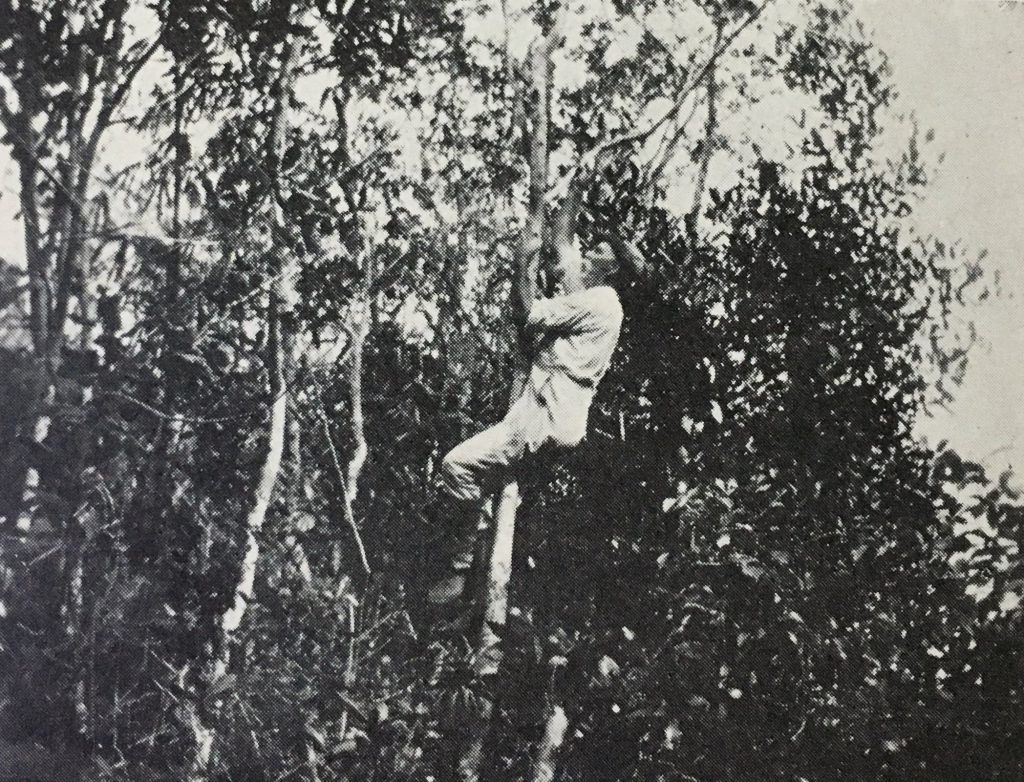

Not all Simpson’s misadventures involved insects. He captured one such experience on film for posterity. First, his description of the event, his attempt to step out of a boat onto terra not-so-firma; note that he calls himself “the old man” in this narrative:

Running along the canal [near Moore Haven, Florida] the Doctor [J.K. Small] saw a rather inviting field for plants and the boat came in to the edge of it. There seemed to be some delay about finding a suitable place to land and as there was a fine lot of freshwater mussels in sight and the bank was fully three feet high and looked dry and firm the old man [Simpson] got his collecting outfit and made a flying leap out on to it. When he finally settled into place he careened over and his entire right arm and leg were buried in the soft mud of which the deceptive shore was composed. At once the entire gang aboard fell over and laughed until they cried, and when at last the Doctor was able to sit up, he declared that it was simply a scientific calamity that he couldn’t have had the camera ready and taken a photo of the performance. He said so much about it that the old man, rather than being a disaster to the cause of science went to where he had alighted and fitted himself into the mud again and was photographed. The episode was referred to afterwards as “The Landing of the Pilgrim Father.”

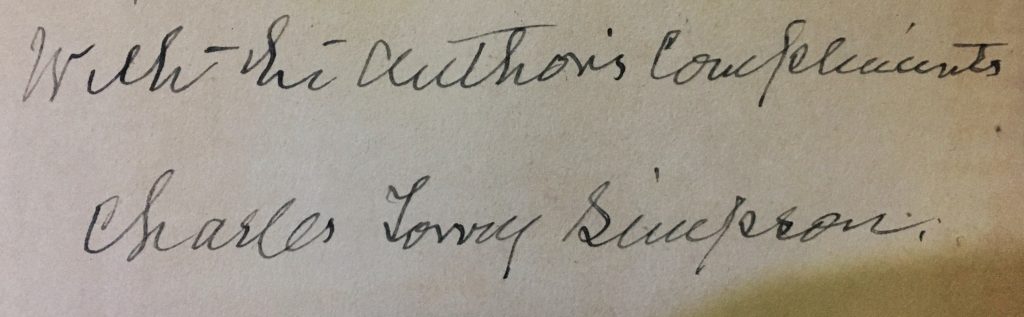

Finally, to close out this post, I will include a picture (literally) of what lengths (or heights) Simpson went to in quest of his snails. This episode, which took place during a visit to Lignumvitae Key:

As I went along I saw at some distance high on a slender tree something which looked like a white Liguus, but it seemed to be altogether too large, I hastened back and found to my astonishment that it was an enormous specimen which, although it was more than thirty feet above me, I was sure was the largest I had ever seen. I at once set my wits to work to secure it…..

It looked so large and handsome that I determined I would try to shin up to it. Shining a tree is pretty good exercise for a young fellow, but for a man nearly seventy-three and weighing more than a hundred and seventy-five pounds it is a good deal like hard work. However, I slowly pulled myself up and whenever I was completely exhausted I clung tightly to the tree and rested. The slender trunk swayed over so that I feared it would break, and once I made up my mind I would not attempt to go any further but the sight of the great, glittering jewel above me tempted me to go on and risk it. At last by reaching out as far as possible I could just touch it with the tip of my finger; then one more tremendous effort and I held it in my hand. I carefully loosened it, put it in my overalls pocket and in about the time it takes to tell of it I slid to the foot of the tree. Then I took it out; I fairly shouted and capered about like a happy boy; I rubbed it against my cheek and lovingly patted it; I talked. foolishly to it. No miser ever gloated over his gold as I did over that magnificent snail.

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN A DELIGHT TO READ — AT TERMS INSPIRING AND AMUSING. Simpson evokes a Florida before development took so much of it, though quite a bit of the degradation actually happened in the author’s lifetime. For instance, here is his account of how much damage had already befallen Lake Okeechobee, including his prediction for its future that is frightfully accurate:

All the glamor and mystery which once surrounded the great lake, all the wildness and loneliness, its beauty and grandeur, its peace and holiness are fast disappearing before the advance of the white man’s civilization and soon it will be only a sheet of dirty water surrounded by truck gardens and having winter homes on its eastern shore. Its rare birds and other wild fauna are gone forever, even the fish which once swarmed its waters are far less abundant than formerly. Its splendid forests are a thing of the past and in their place we will have a lot of cheap bungalows and atrocious plantings of exotics. It should have been preserved as a state or government reservation where its rare flora and rich wild fauna, its mystery and beauty could have been kept forever.

Sadly, it is virtually impossible to find a copy of Simpson’s book nowadays. Until 2017, no printed work newer than 1922 could be scanned for online reading, or published as low-cost on-demand printed paperbacks. (This has supposedly now changed, as this article reports; however, I expect it will be a considerable time before the largely volunteer world of book scanners catches up.) For Out of Doors in Florida, this meant that my only options were to find one in a university library, or purchase one online for a small fortune. Even if I could locate a library copy, I would be stuck in the library for a couple of days, reading it and writing my post. Because that was unrealistic given my daily work demands, I took the latter route, and I have to say this is the most I ever paid for a book (and it was supposedly on a one-week sale on eBay). Suffice it to say that I am delighted that my copy includes Simpson’s complete autograph (he usually signed his letters Chas. T. Simpson).

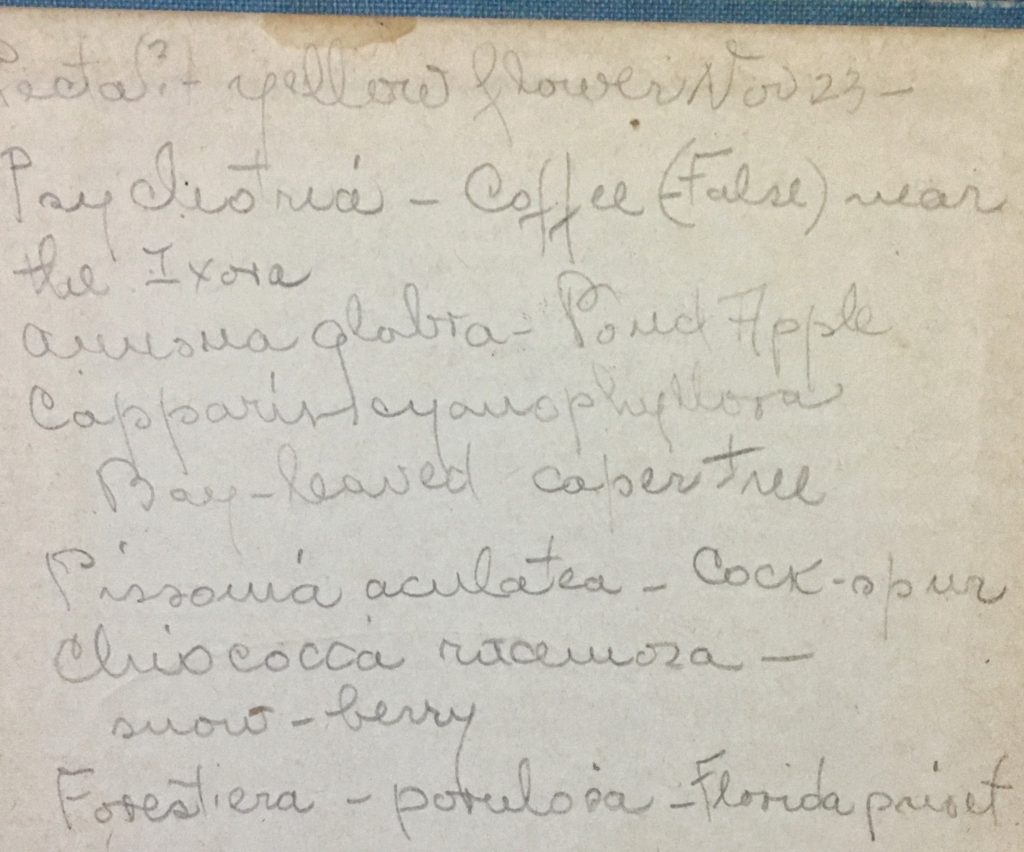

In terms of the volume’s history, it was formerly the property of the Park East Mobile Home Club, on the Tamiami Trail in Sarasota. One reader/owner filled half the inside back cover with listings of native plants, both common and Latin names, in pencil. I think Simpson would have been pleased to see the book put to such use.