Barbed wire emerges from tree stump, Little Mulberry Park. 26 Dec. 2013

Mid 20th Century stacked rock piles, Madison County, North Carolina. From Early Georgia article by Thomas Gresham (1990).

What do the stone piles of Little Mulberry Park in Gwinnett County have to tell us about the past history of the area? If they are not prehistoric burial and ritual sites, what other possibilities remain? In this final blog post in my series about this stone mounds, I will explore another explanation for their origin, one that relates them to the past agricultural history of the area. Evidence that the land was once open pasture can be found in the large pasture trees that follow former fence lines (see my post from 12/28 for an example), and bits of barbed wire that emerge from old tree stumps in the park.

But why would settlers choose to pile up rocks on the property in the first place? Patrick Garrow, the archaeologist who did the initial investigation of the site in 1988, argued that the stone piles locations and structure argued against the stones having been piled up by farmers clearing the ground for planting. Indeed, since the land was never tilled but only used for pasture, that explanation seems unlikely. Perhaps the farmers wanted to clear the ground so that there would be more graze for their animals, or so that the animals would be less likely to injure themselves? Why, then, go to the trouble of stacking the rocks?

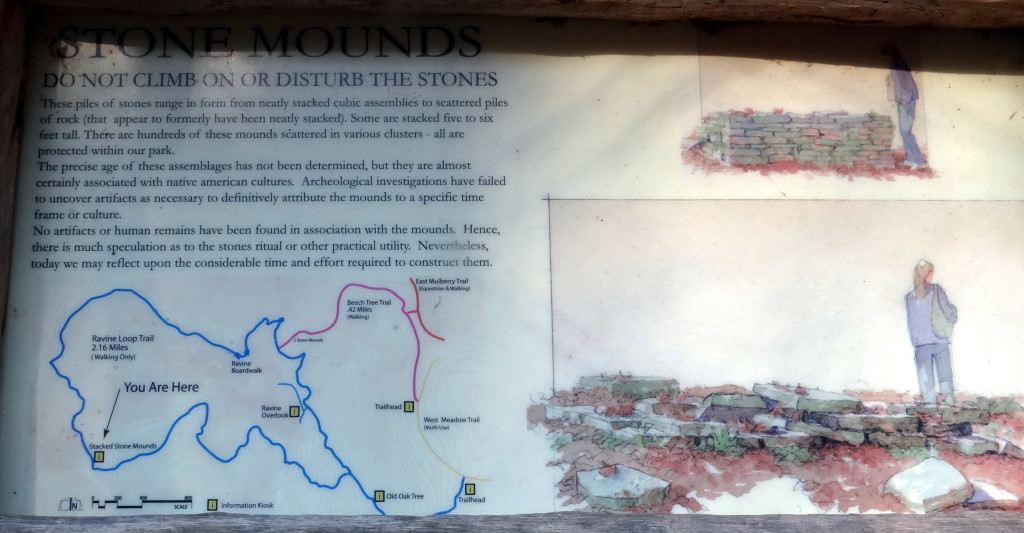

It is the fact that the rocks were stacked which convinces many people that the mounds are evidence of a prehistoric origin. Clearly, someone (or someones, plural) went to considerable effort to place the rocks in layers that can still be seen today. In fact, as archaeologist Thomas Gresham argued in an Early Georgia article in 1990, southern farmers have stacked rocks into cylindrical piles like these within recent history. In his paper, entitled, “Historic Patterns of Rock Piling and Rock Pile Problems”, Gresham included photographs of such rock piles. Before 1940, Gresham explained, flat rock and flagstone quarrying in Georgia was “small scale, localized, and done by hand.” Stones found close to the surface of the ground would be pried up with crowbars, sorted, and stacked for temporary storage until being sold for use building chimneys, terraces, foundations, and steps. Why, then, would so many such stone piles have survived in Little Mulberry Park? Perhaps, Gresham proposed, the stone proved inferior for use, and did not sell, or there was some other event that prevented a sale from going forward, or alternative building materials (such as brick) become widely available and prevented the stone from being sold.

Beyond the documented historic occurrence of such piles on North Carolina farms, is there other evidence to support the idea that the structures are historic stone piles rather than prehistoric Indian mounds? In fact, there is archaeological evidence to support this idea. In 1995, Thomas Gresham excavated eight stone piles at the Little Mulberry Park site. He found no prehistoric artifacts, but he did unearth early 19th century artifacts (ceramics, glass, and metal, including an 1838 penny) beneath two of the piles, conclusively showing that both were constructed in historic times. During the excavation, Gresham’s team also found evidence of a former small-scale rock quarry in the vicinity of the piles, lending further credence to the idea that stone was being cleared from the land and stockpiled in the area.

Ultimately, we will probably never know for certain what cultural forces shaped the stone piles at Little Mulberry Park. In my own explorations, both on-ground and via the Internet, I am satisfied that the piles are not prehistoric at all, but were built by settlers gathering field stone for future construction efforts. I suspect that this explanation will be less than satisfactory to many who have visited the park or who read enthusiastically about Mysteries from the Past. There is a certain allure in thinking that the stone mounds were constructed by Native Americans thousands of years ago as part of a mysterious ritual. Many human beings are hungry for the sacred, and find solace in the mythical prospect of a distant time when people lived in harmony with nature, leading lives deeply connected to their communities and to the forces animating the cosmos. To say that the stone piles are actually Indian mounds is, I will admit, a much more enticing story. And maybe that is why the information sign at the park, rather than proposing several different theories behind the stone structures, instead declares to this day that they are “almost certainly associated with native american cultures.”