“Somewhere in the depths of the forest you will meet the Creator. The place is the culmination of His plan for men adown the ages, a material thing proving how His work evolves, His real gift to us remaining in natural form. The fields epitomize man. They lay as he made them. They are artificial. They came into existence by the destruction of the forest and the change of natural conditions. They prove how man utilized the gift God gave to him. But in the forest the Almighty is yet housed in His handiwork and lives in His creation. Therefore step out boldly. You are with the Infinite.

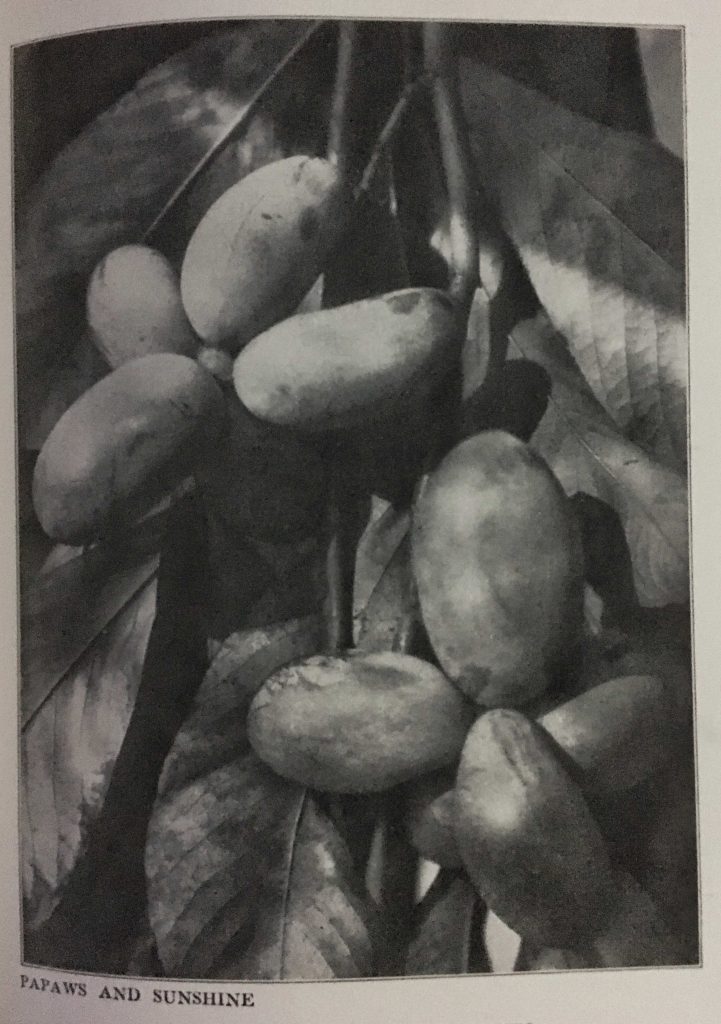

AFTER READING OVER THREE HUNDRED PAGES OF GENE-STRATTON PORTER’S BOOK, “THE MUSIC OF THE WILD”, I AM UNSURE WHERE TO BEGIN; SO I WILL BEGIN WITH THE PAWPAWS. The ripening pawpaws on my backyard tree offer me an immediate and direct connection to her work. The book is laden with her original photos. Taken sometime prior to the book’s publication in 1910, they represent some of the earliest nature photography in America. Only four years earlier, in 1906, National Geographic had published its first photographs of wildlife. Across 110 years, I find a sense of connection and belonging. It is relatively easy for me to find those points of contact through her photography; her text, however, frequently leaves me feeling adrift in a foreign land. For Gene Stratton Porter, everything exists by design of God, and was carefully brought into being in order to meet the human needs. To go into the deep woods is to enter a cathedral in a quite literal sense. Nature brings humans delight fundamentally because nature is the handiwork of a Supreme Being.

THERE ARE OTHER OBSTACLES TO APPRECIATING THIS BOOK. She tends to anthropomorphize most everything, from a calling songbird to a flowing stream. In the case of animal calls, she frequently translates them into everyday human speech with less than inspiring results. For instance, she proposes that a calling heron could be saying “Come my love, this spot is propitious. Share a morning treat with your dearest,” or might intend to mean “Better keep away, old skin and bones; there’s danger around this frog pond.”

AND THEN THERE IS HER RELENTLESS “POETRY”. The lovely black and white photographs, some the result of hours spent atop a ladder in her orchard, are each accompanied by a few lines, usually rhymed. Some innocuous passages are taken from other poets, like Emerson or Whitman. Others are snippets of doggerel she dreamed up, best forgotten as quickly as possible after reading them. For instance, consider this one: “The screech owl screeches when courting, / Because it’s the best he can do. / If you couldn’t court without screeching, / Why, then, I guess you’d screech too.”

FOR THOSE THAT SURVIVE POETRY THAT WOULD PUT A VOGON TO SHAME, AND ENDURE HER INSISTENT CHRISTIANITY, THERE IS MUCH TO BE GAINED FROM SPENDING AN AFTERNOON WITH STRATTON-PORTER. Although not a professional scientist, she carefully observed the workings of nature in and around Limberlost Swamp in northern Indiana. She took photographic sequences documenting breeding birds, from nest-building to the first flights of the young — in some cases, being the first to do so for particular species. As she explained early on in the volume,

Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras. Such wonders are lost by specializing on one subject to the exclusion of all else. No doubt it is necessary for someone to do this work, but I am so glad it is not my calling. Life has such varying sights and songs for the one who goes afield with senses alive to everything.

THROUGHOUT THE BOOK, STRATTON-PORTER CELEBRATES THE RICH PLANT AND ANIMAL LIFE OF RURAL INDIANA — THE MOTHS, THE BIRDS, THE FROGS, THE BATS. She takes delight in celebrating what others would pass off as mundane. “I sing for dandelions,” she announces proudly. “If we had to import them and they cost us five dollars a plant, all of us would grow them in pots. Because they are the most universal flower of field and wood, few people pause to see how lovely they are.” After essays on the forest and the field, she closes the book with a paean to the life of the swamp and its rich music:

It is the marsh that furnishes the croakings, the chatter, the quackings, the thunder, the cries, and the screams of birdland…. At times we may think that we would be glad not to hear again the most discordant of these musicians, but they are all dear in their places, and were any of them to become extinct, something of its charm would be taken from the damp, dark, weird marsh life that calls us so strongly. We have learned to know and understand them, and they have won our sympathy and our love.

IF STRATTON-PORTER DEPICTS HER LIMBERLOST LANDSCAPES AS AKIN TO PARADISE, THERE IS A SERPENT IN THE GARDEN: HUMANS. Lurking in the passage above is the possibility of extinction, something naturalists were just beginning to come to grips with then. Four years after the book was published, Martha, the last known passenger-pigeon, died. Concerned over what was being lost, Stratton-Porter wrote bitterly of the wanton destruction of waterbirds for the millinery trade, and the trampling and picking of wildflowers by unthinking nature tourists. And already in her day there was abundant evidence of how humans were altering the land — turning forests into agricultural fields and draining the swamps. In my opinion, without a doubt the most perceptive passage in the book is one where she considers, the bigger picture — how humans were even beginning to alter Earth’s hydrologic cycle:

It was Thoreau who, in writing of the destruction of the forests, exclaimed, “Thank Heaven, they can not cut down the clouds!” Aye, but they can! That is a miserable fact, and soon it will become our discomfort and loss. Clouds are beds of vapor arising from damp places and floating in air until they meet other vapor masses, that mingle with them, and the weight becomes so great the whole falls in drops of rain. If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distil moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, — they prevent vapor from rising; and if it does not rise it cannot fall. Pity of pities it is; but man can change and is changing the forces of nature.

ALAS, IT WAS A WARNING THAT NO ONE HEEDED. When the first water cycle diagrams appeared two decades later, they depicted an entirely natural process, from which humans were absent. That is still the case in most hydrologic cycle diagrams available today. In a recent Nexus Media article on human impacts on hydrology, Dr. David Hannah from the University of Birmingham remarked that “Nearly a century ago, human impacts were less extensive and less understood. But we have no excuses now not to include people and their various interactions with water in a changing world.”

AS AN AFTERWARD, A FEW REFLECTIONS ON THE COPY THAT I READ. When this first edition copy of “Music of the Wild” first arrived in the mail many weeks ago, I immediately thought back to my penchant as a child for removing book jackets and disposing of them. Here, I really wished the jacket had been retained, as the outside of the book is rather soiled, detracting a bit from the charm of its gilt gold lettering against a green background. Making the spine white was not particularly wise to begin with; it definitely shows its age. In terms of the volume’s history, all I can say is that it once belonged to Jean Kerr, who wrote her name on the top of the first page in flowing pencil. The most notable characteristic of the book is its weight: 2.4 pounds, according to a bathroom scale. Every sturdy page of text is followed by an even thicker page with a photograph on it; there are literally over a hundred photographs included in the volume. What a magnificent “coffee table” tome it must have been, 110 years ago.