“One may stand upon a mountain-top and behold the splendors of awful immensities, but the imagination is soon lost in infinity, and only the atom on the rock remains. The music of the swaying rushes, the whispers among rippling waters and softly moving leaves, and the voices of the Little Things that sing around us, all come within the compass of our spiritual realm. It is with them that we must abide if we would find contentment of heart and soul.”

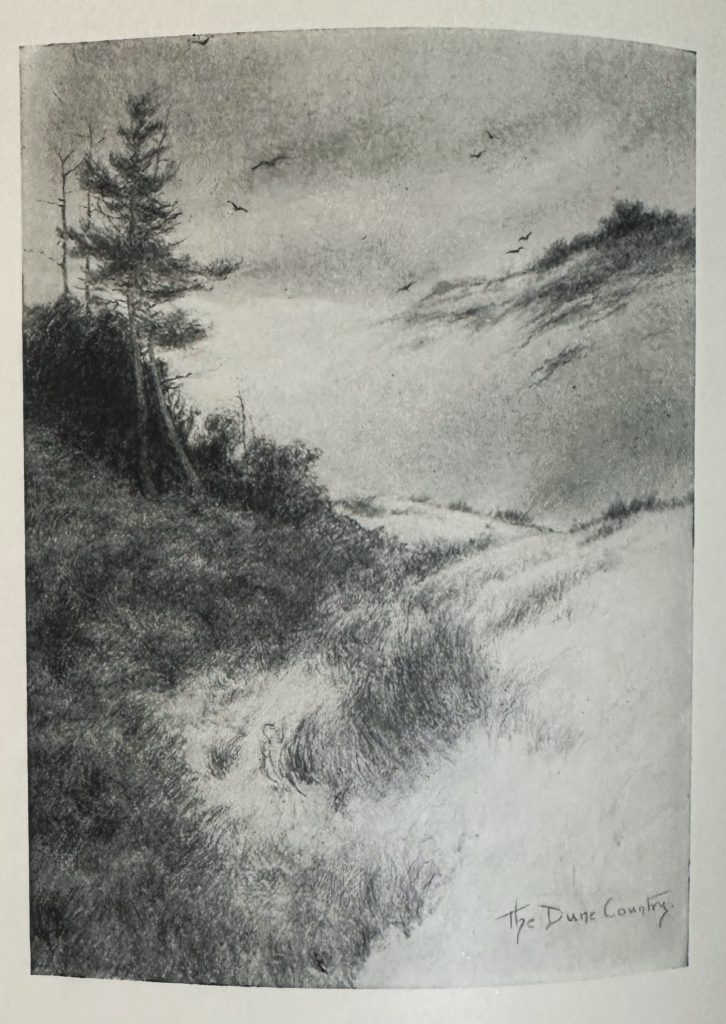

Earl Howell Reed (1863-1931) was, first and foremost, a self-taught artist. After working for 20 years as a grain broker for the Chicago Stock Exchange, he gave it up to pursue a dream of becoming an artist and author. He found inspiration among the Indiana Dunes, returning many times and publishing three books of his etchings of the dune landscape and people; seventy-seven of his original works are now in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, while five others (particularly stunning) are held at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, though none is currently on display. Ironically, though, for all the lovely black and white images that fill The Dune Country, the book is as much a celebration of sound as of vision. For all its “appealing picturesqueness,” the Dune Country is most marked by the richness of its wild music. The Dune Country was Reed’s second book; his first, primarily artwork with brief text accompaniment, was titled, The Voices of the Dunes. In a chapter on gulls and terns, Reed explains that

“The voices of the dunes are in many keys. The cries of the gulls and crows — the melodies of the songsters — the wind tones among the trees — the roar of the surf on the shore — the soft rustling of the loose sands, eddying among the beach grasses – — the whirr of startled wings in the ravines — the piping of the frogs and little toads in the marshy spots — the chorus of the katydids and locusts — the prolonged notes of the owls at night-— and many other sounds, all blend into the greater song of the hills, and become a part of the appeal to our higher emotions, in this land of enchantment and mystery.”

And the voices, for the most part, come from the Little Things. I find it fascinating how Reed chooses to take a label for smaller living creatures and capitalize it, so that collectively, those Little Things are, in fact, beings of much power and beauty. Reed explains, a page before the quote above, why he is inspired by them:

“The love of the Little Things which are concealed from the ordinary eye comes only to one who has sought out their hiding-places, and learned their ways by tender and long association. Their world and ours is fundamentally the same, and to know them is to know ourselves.

We sometimes cannot tell whether the clear, flutelike note from the depths of the ravine comes from the thrush or the oriole, but we know that the little song has carried us just a little nearer to nature’s heart than we were before.”

For all the beauty Reed finds among the dunes, there is wildness here, too — a fierce wildness that cannot be escaped.

“The herons stand solemnly, like sentinels, among the thick grasses, and out in the open places, watching for unwary frogs, minnows, and other small life with which nature has bountifully peopled the sloughs. The crows and hawks drop quickly behind clumps of weeds on deadly errands in the day time, and at night the owls, foxes, and minks haunt the margins of the wet places. The enemies of the Little Things are legion. Violent death is their destiny. With the exception of the turtles, they are all eaten by something larger and more powerful than themselves.”

Tragically, the love and care Reed expresses for the wild landscape of the dunes is not shared by everyone. Early on in the book, Reed complains about how

“Man has changed or destroyed natural scenery wherever he has come into practical contact with it. The fact that these wonderful hills are left to us is simply because he has not yet been able to carry away and use the sand of which they are composed. He has dragged the pines from their storm-scarred tops, and is utilizing their sands for the elevation of city railway tracks. Shrieking, rasping wheels now pass over them, instead of the crow’s shadow, the cry of the tern, or the echo of waves from glistening and untrampled shores.”

Much later in the book, Reed encounters a farm family living a hardscrabble existence in the backcountry behind the dunes. The family kept a raccoon they had saved as a baby after the rest of its family had been killed by dogs in a coon hunting outing. They kept the raccoon chained beside a wooden box in their front yard. The sight of it prompted Reed to declare, “It is mankind that does these things — not the brutes — and yet we cry out in denunciation when humanity is thus outraged. We chain and cage the wild things, and shriek for freedom of thought and action. Verily this is a strange world!”

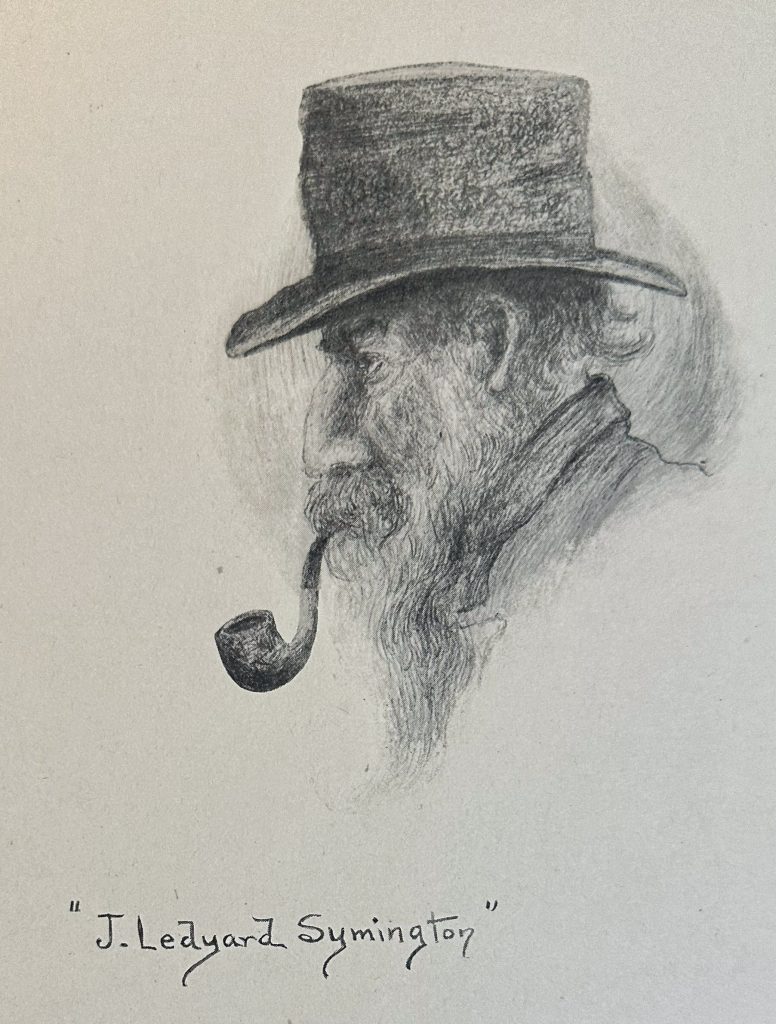

For all his fascination with wild beauty in sound and scene, Reed spends much of his book sharing about the unusual human characters he encounters living in various isolated shacks throughout the dune country. He sketches their facial profiles at every opportunity, and in his visits with them documents their stories (believable or otherwise). Overwhelmingly old men, these dune residents are “old derelicts,” human flotsam cast ashore among the dunes, living on the edge of civilization, usually by choice:

“While we may be interested and amused with the petty gossip, the rude philosophy, the quaint humor, the little antagonisms, and the child-like foibles of these lonely dwellers in the dune country, the pathos that overshadows them must touch our hearts.

They have brought their life scars into the desolate sands, where the twilight has come upon them. The roar of a mighty world goes on beyond them. Unable to navigate the great currents of life, they have drifted into stagnant waters.”

The accounts of these eccentric souls are well worth reading. I could even imagine constructing a one-act play around them and their stories.

I greatly enjoyed The Dune Country for its haunting prose and fascinating depictions of the people who lived there, as well as its fine etchings. Reed was an artist and observer, not a naturalist, of course. His bird classification extends no further than “gulls”, “terns”, and “crows”. He does remark, a bit wistfully, on how being able to identify songbirds might enrich our appreciation of them: “If we could see the singer and learn his name, his silvery tones would be still more pure and sweet when he comes again.” But he is far more fascinated by the music and poetry of Indiana Dunes than the ecological relationships he encounters there. Yet his descriptions are evocative, and effectively transport the reader (or me, at least) into the world of the dunes. For instance, he writes about how “Swamps of tamarack, which are impenetrable, contribute their masses of deep green to the charm of the landscape. The ravagers of the wet places hide in them, and the timid, hunted wild life finds refuge in their still labyrinths. In the winter countless tracks and trails on the snow lead into them and are lost.” Reed’s gift was not lost among contemporary readers, however forgotten his works are today. As Annex Galleries claims, “Reed brought so much attention to the Dunes and the need to conserve the natural habitat that the Indiana State Legislature established the Indiana Dunes State Park in 1923.”

Finally, a few words about the provenance of my edition of this book. It is a first edition, but was also the only edition ever published. It appears to have been owned by two people in the past 110 years. One signed his (her?) name in the upper right-hand corner of the flyleaf. The second stamped his name on the lower left-hand corner of the front end sheet. I am guessing, from the style of the signature, that it belongs to the first owner. I honestly cannot read the name with any confidence. If anyone reading this blog can offer a translation of the script, please leave a comment here, as I would very much like to know who they were.

The second name, Harold Phelps Stokes, actually belongs to someone of some renown. He served on the Editorial Board of the New York Times between 1928 and 1937. He also traveled to Alaska on Warren G. Harding’s ill-fated journey (Harding died in California on the way home.) and was a friend of Herbert Hoover. Stokes wrote editorials regarding state and city affairs in New York, along with problems relating to transit and traffic. In vain I sought some connection between his life and travels and Indiana Dunes, but that connection, if there ever was one, appears to belong to Elemental Mystery (to use another term of Reed’s).