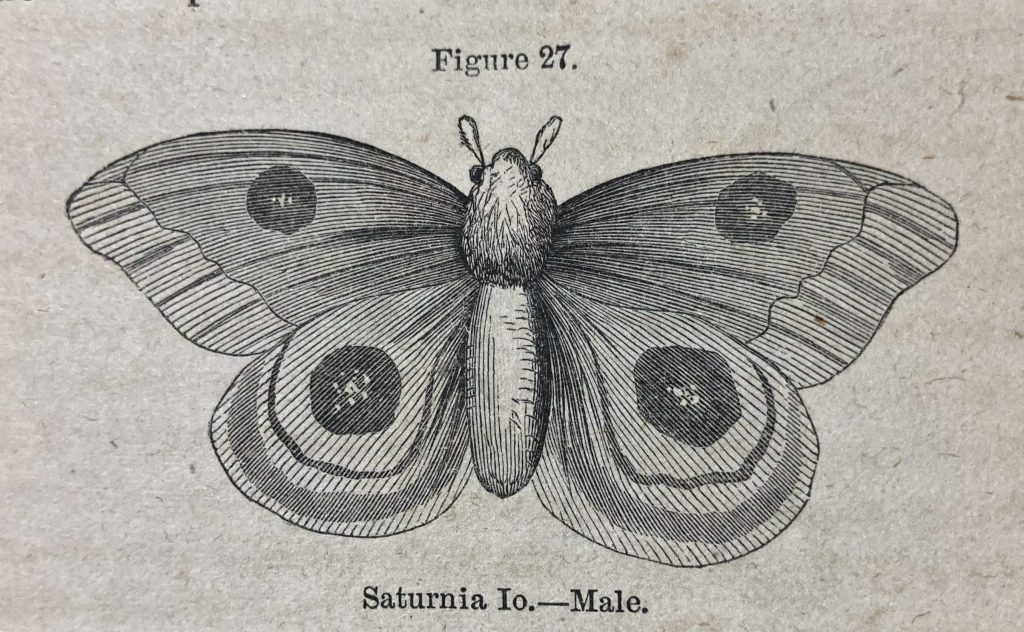

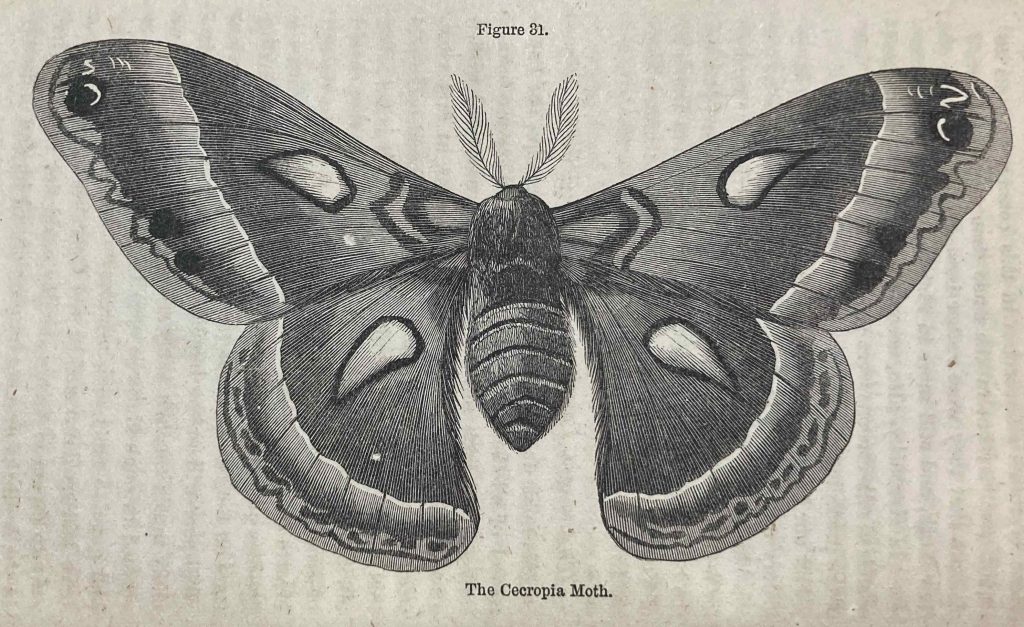

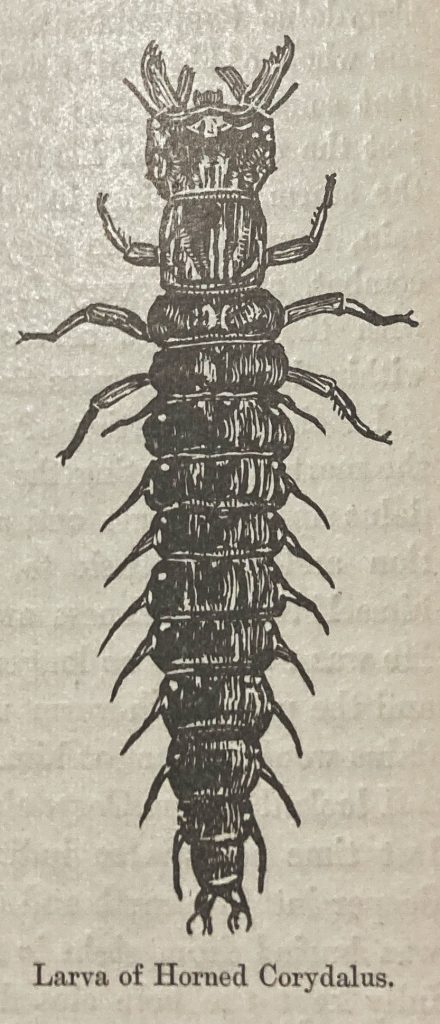

For my latest book, I have chosen Volume 4 from The Riverside Library for Young People, Up and Down Brooks by Mary E. Bamford. At a bit smaller than five by seven inches, this little tome invites smaller hands or perhaps the pocket of a knapsack. The book itself is a carefree romp with a quirky, playful, scholarly “self-named “bug-hunter” as she makes her way up and down brooks, armed with a cloth dredger and a bucket, collecting water beetles and anything else she can find in the streams of Alameda County, California. Along the way, at an (and every) opportunity, she makes some sort of connection to classical or medieval history, culture, and literature. The result is, well, exhausting. Perhaps her literary allusions were common to readers at the time (maybe even younger ones), but most of them were entirely lost on me. As a guidebook for how to study streams, the book also fails. The reader is halfway through the text (of over 200 pages) before mention is made of how to make a dredger of one’s own. And there are few common names for insects; instead, Bamford resolutely names them by genera. Thus, a hellgrammite becomes “larva of horned Corydalus,” and the adult dobson-fly is simply “Horned Corydalus.” Who are her readers, then? How many children would have a clue what her various insect names signify? At the same time, some of her playful passages definitely seem best suited to a child (or childlike adult). Consider her experiences with a captive predacious water stick-insect, Ranatra (again, the genus name):

I think Ranatra had no music in his soul, and he probably never missed the bird-twitterings of his native brook. As a personal favor and a reminder of the days when he lived in the creek, I sometimes took a flute and played “Way down upon the Swanee River” close to his jar. But the calmness with which he received the serenade was only equal to that with which he usually surveyed the world when no music was going on. Neither the “growly” nor the “squeeky” parts of the piano affected his nerves, even when his bottle was placed touching the instrument next the keys.

A page later, Bamford reports on Ranatra’s unexpected death:

Peace to his ashes. I never did know how I loved him until he died. Never did I part from a bug with such regret… The jar looked lonely without him, he had lived in it so long, and I felt half inclined to that, in spite of his having dwelt with them so securely for so long a time, he had at last fallen a victim to those cowardly cousins of his, the scorpion-bugs. They rushed about as usual, evidently caring nothing for the death of the bug that was worth twenty of them.

As the reader can plainly observe, Bamford does not hold back on her feelings about the various organisms she encounters. There is a whimsy to her descriptions and even sometimes abject silliness. Her many failed attempts to raise a tiger beetle larva to adulthood in captivity included the following individuals (forever immortalized in her prose): Conqueror of Coffee-Pot-Lid Lake; Conqueror II; The Hesitator; Larva of Yeast-Powder-Lid Lake; Scarer of Soapdish-Lid-Lake; Triumpher of Tin-Pan Lake; Monarch of Mortar Lake; “The Last”; Oliver; Frightener of Flower-Pot Lake; and “The Last-But-One.” Yet beneath all the craziness and the random references to obscure etymologies and myths, there is also an observant and patient scientist noting the minutiae of lives mostly overlooked at the time. Consider her assessment of a snail’s lot:

Yet the fact of the matter is that there is not much character to a pond-snail. To slip out of a mass of jelly with one’s house on one’s back, to float on the surface of the pond, to dine on leaves or confervae, to rest when weary and to journey when so disposed, to retreat into one’s house when in danger, to pass along through life in a somewhat humdrum fashion with small spirit or vim in one, to cleanse the pool what little one may, and finally to drop down through the water and whiten with one’s lifeless shell the scum of the pond, to have that slime close at last over one’s shell and leave one buried in oblivion while all the pond-life goes on above one still, — this is the snail’s life. Devoid of fighting instincts, not gifted with ambition to soar like the beetles, or to be ever in sight like the skaters, treating all the pond-neighbors with quiet reserve, going one’s own way and doing much good in the world, such is the pond-snail. If he is not brilliant, he is good, and what more could be asked of him?

The respect Bamford grants many f the insects she encounters is not always expressed toward the many local residents, particularly children, who see her with dredger in hand and assume she is trying to catch fish. All too few of them, she complains more than once, have any interest in insects — like this teen who disrupts her work:

“What are you catching? Fish?” demands a voice, and I look up to see the yellow head of an inquisitive foureen-year-old youth peering over the bank.

“Water-beetles,” and I hold up my pail to show the contents.

“What are they good for?” proceeds the utilitarian.

I hesitate a moment. Shall I tell him of the decaying leaves that these numerous Hydrophilidae devour, assisted by these pond-snails; of the yearly plague of frogs from which we are delivered by the disappearance of the juices of the polliwogs through the proboscides of these water-boatmen; of the multitudes of mosquitoes who never have a chance to bite us, because as wigglers they have met their fates under the masks of these dragon-fly larvae? I excuse myself from this lesson on zoology, and make answer, “I take them home and keep them, and study their habits.”

What motivates Bamford to make such a study of stream life, especially insects? At one point in her ramblings, she shares this early memory with her readers, offering a window into her motivations:

I remember the day when the idea first entered my brain that other creatures than human have interesting lives. I must have been about eight or nine years old. I had been taking a walk in a little mining town among the Sierra Nevada foothills. A minister was with me, and he had a hand-microscope or glass in his pocket.

We sat down under the trees on a hill somewhere back of a church, and he showed me through the glass a multitude of little creatures living in the heart of a yellow flower… I remember that as a very wonderful day, one on which I did not see half enough through that glass to suit me, but still one on which I obtained a glimpse of a world very different from that in which I usually lived.

Indeed, it is a world with very different rules. Toward the book’s close, Bamford remarks on “how hard-hearted the insects are toward one another! In all the time I have watched them, I do not recollect ever having seen an act of compassion performed by any kind of insect for another.” She then proceeds to describe her experiences waiting for a caterpillar to pupate, only for many parasitic flies to emerge instead, having fed upon the caterpillar’s body. Yet through this all, she ultimately conveys a sense of wonder and delight in this foreign world beneath the water’s surface.

And so the traveler beside this brook and over these hills may learn, if he looks, that man is not the only creature who builds houses and is disappointed about living in them. There is material here for a fine sermon after all, take the brook through and through. Here are fightings and murders and thefts and trickeries, the semblance of death, the awakening from slumber, the rising to new life, the change from the grovelling on the earth to the soaring of wings in the sunshine.

And the ultimate point of the sermon? Here, Banford slips back into a comfortable corner within Nineteenth-Century American Christianity, declaring fervently that “The majority of people scarcely pause to realize that the different kinds of creatures represent so many of God’s different thoughts and that it might possibly be worth while to glance at the things that He has deigned to place on earth.”

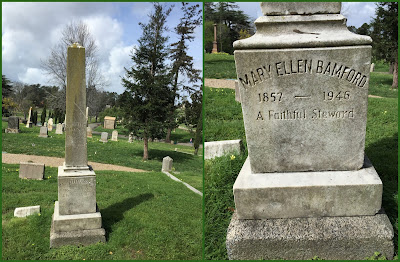

And what of Mary Ellen Bamford? She was born to a pioneer settler couple in Healdsburg, California, in 1857. After attending public school in Oakland, she worked for four years as an assistant in the Oakland Free Public Library. After that, she became a full-time writer, producing over a dozen books, including several titles for the American Baptist Publishing Society. She was a prohibitionist and advocate for Asian immigration into the US. She died in 1946 at the age of 88.

My first (only) edition of this book was previously in the collections of the Reed Free Library in Surrey, New Hampshire.