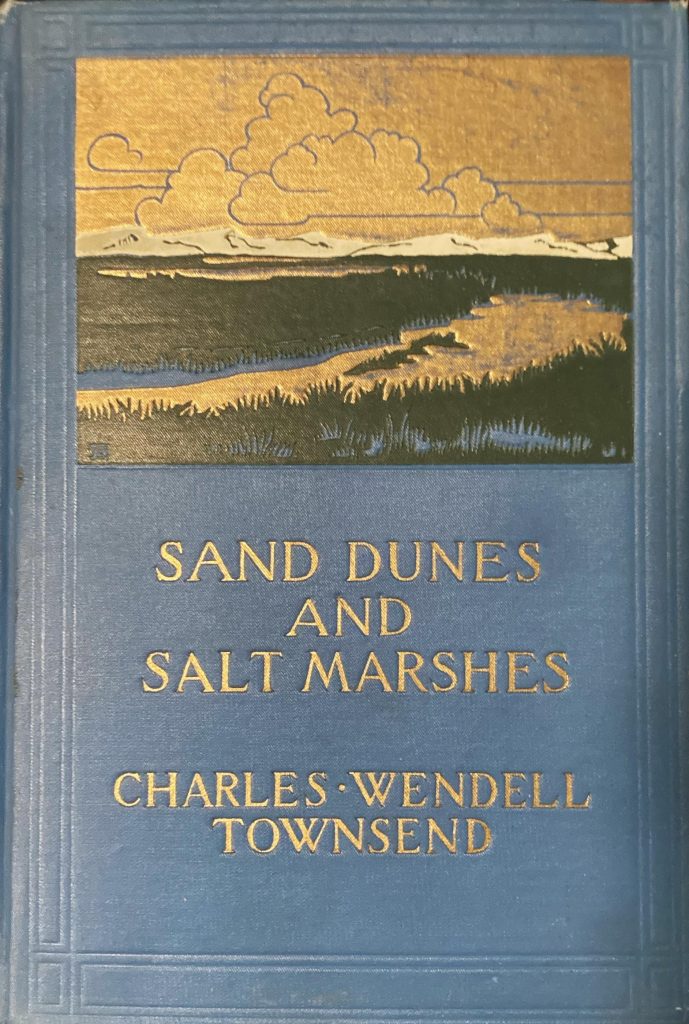

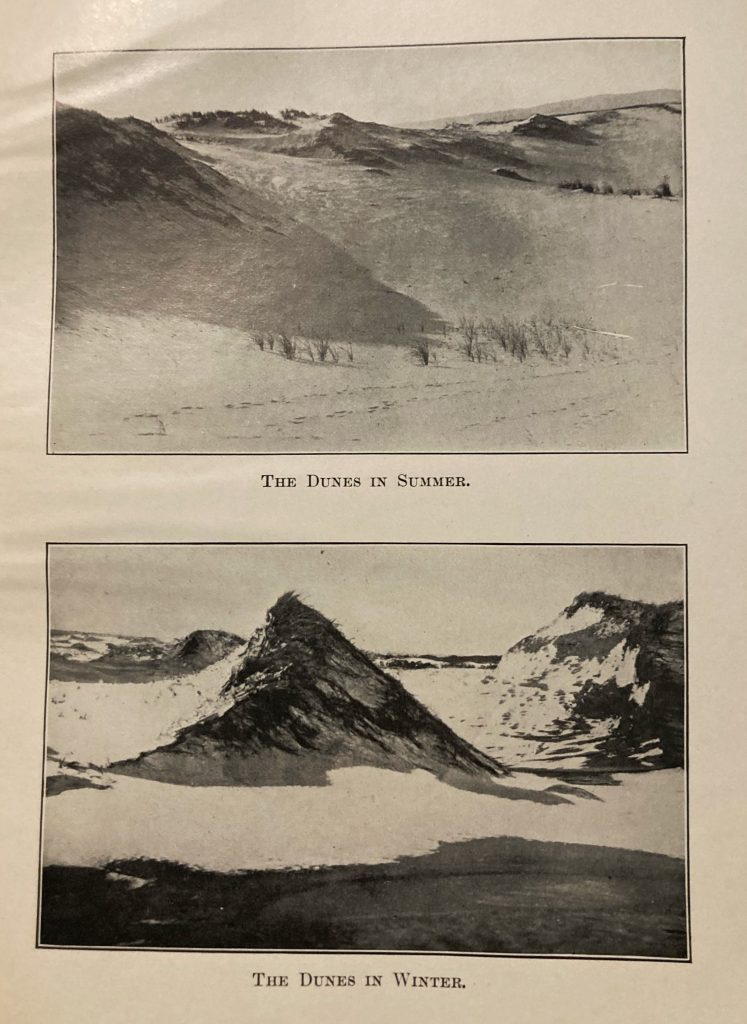

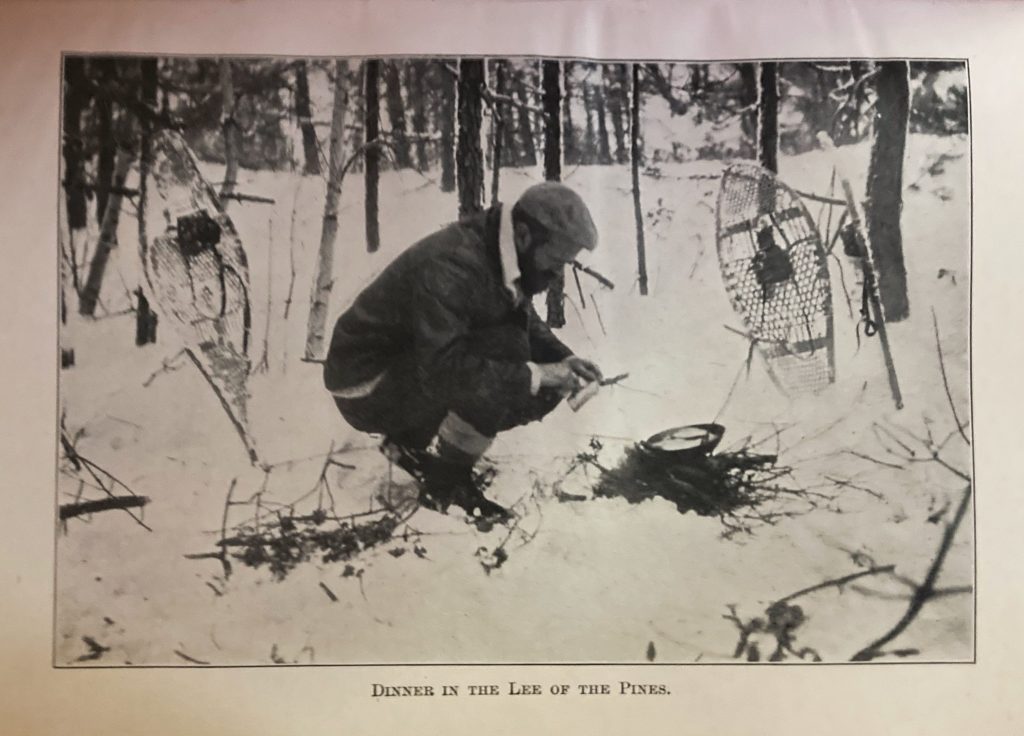

Charles Wendell Townsend, MD was born in Boston in 1859, “of good old New England stock” (as an “In Memorium” piece by Glover Allen in The Auk puts it). He developed an early interest in birds, which at the time mostly involved collecting eggs and shooting “specimens”. In 1885, Townsend graduated from Harvard Medical School as a Doctor of Medicine. He married Gertrude Flint of Brookline, Massachusetts, and set up a private practice in Boston. In 1892, he built a summer house on a ridge overlooking a coastal marsh in Ipswich, Massachusetts, just north of Cape Ann. He would spend both summer vacations and weekends there over many years, increasingly opting to observe nature with binoculars and telescope instead of a gun. His particular interest was the land and shore birds frequenting the area, but he also closely observed changes in the dunes over time; the dunes took on a very different appearance in the summer than in the winter. He traveled extensively through the marshlands by boat, and became closely acquainted with the region’s natural history, including its geology (with its “pleasures and possibilities”). Remarking that “I have sometimes been asked what I found of interest in the dunes and marshes,” Towsend explained that “This little book [Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes] is the answer.” He published it in 1913, followed by Beach Grass in 1923. (That book will be explored in a future post.) Travel was another facet of Townsend’s life; he made several trips to Labrador, first by steamer and later by canoe, publishing several books about the region, particularly its human and bird life (at least one volume of which will also be covered in this blog at some point). He continued to travel extensively (including around the world) up to the time of his passing in 1934.

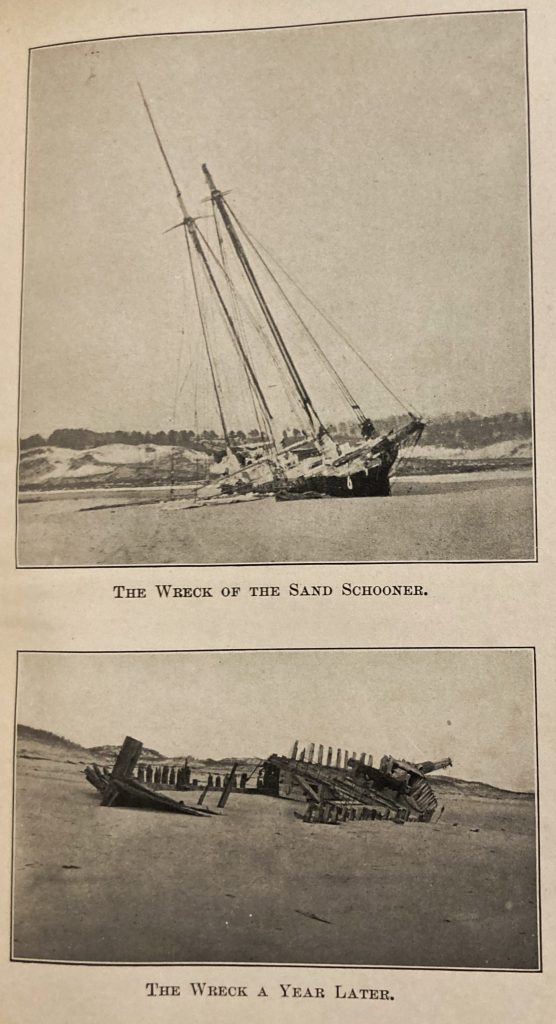

Taken as a whole, the book is a tribute to the rich natural history of the dunes and marshes of northern Massachusetts over one hundred years ago. While the text at times feels a bit dry (rather like the dunes themselves), Townsend’s photographs throughout are a delight. They depict landscapes at the time, animal tracks through the dunes, marsh haying operations, and a few images of the wildlife itself. Because he returned so frequently over many years, Townsend was able to document changes, such as the image below of a shipwreck soon after it happened and again a year later. For much of the book, I struggled a bit with his prose. I did enjoy his chapter on tracks in the dunes, where he identifies dune visitors by their tracks, and their meals by investigations of scats and bird pellets. He closes the chapter by declaring that “The study of ichnology and scatology in these sandy wastes is as absorbing as a detective story.” His bird chapters that followed were informative but so laden with bird descriptions (and, alas, no bird close-up photographs) that they were tough going. I think the main challenge to the reader is that Townsend himself is largely absent from most of the volume, stepping aside to report scientifically what he has seen. Oddly, though, the book is also interspersed with chunks of poetry — some identified by the author, others not (Townsend’s own writing?). Here, again, is that concept of the time, that effective nature writing combines both the scientific and the poetic sensibilities. Unfortunately, in this case, the two are mostly kept separate.

The tone changes when Townsend reaches the salt marsh. Here, his voice strikes an enthusiastic, joyful tone that is uncommon in the rest of the book. Consider this passage describing the salt marsh in late summer:

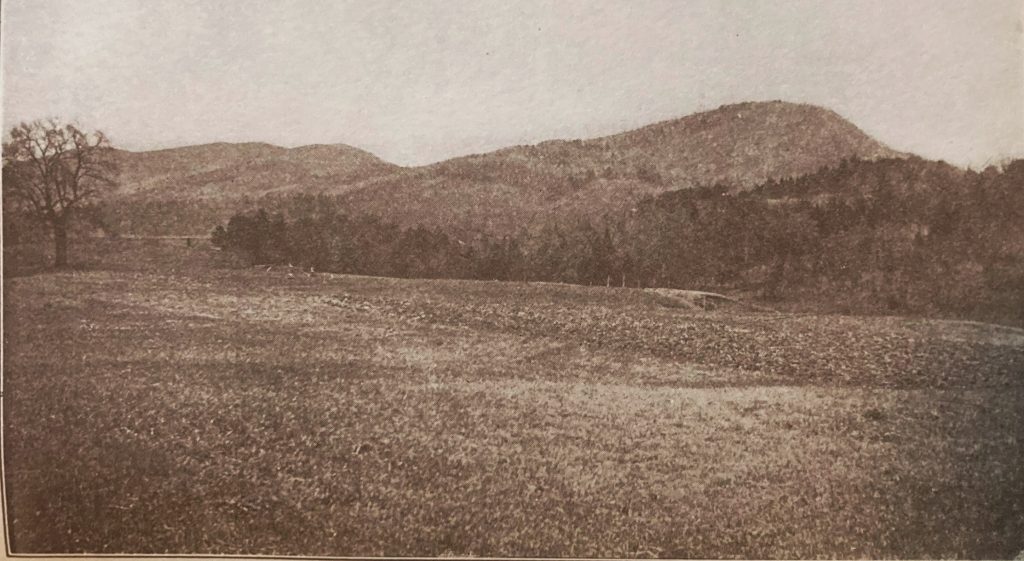

All the marsh vegetation is at its height of luxuriance in mid-August. Then the marsh lies brilliant in the sunlight, a broad expanse, flat as a floor and glowing in yellow-greens, touched here and there with washes of buff and of chestnut.

Fringing its upper edge is the broad band of the mourning black-grass, while the rich dark green of the thatch threads invisible serpentine creeks, and borders the ribbons of water that wander hither and thither like tortuous veins through the marshes, reflecting the brilliant blue of the skies. There are wonderful plays of light and shade as cloud shadows chase each other over the surface of the marshes, or as the lengthening shadows of the hills extend their range with the declining sun. On windy days the tall thatch bends before the blasts, and shimmering waves like those on the surface of the water pass over it.

On such days, with the wind in the north- west quarter, the air is exceedingly clear, and every wooded island and distant hill stands out with great distinctness, while the creeks take on an intense blue which contrasts strongly with the light green of the marshes.

The tides creeping over the sand flats, swell- ing the creeks, obliterating the brown banks and drowning the tall thatch, bursting out in unexpected veins and pools throughout the marshes,-all this, notwithstanding its twice daily repetition, is never other than a miracle.

or this passage about exploring the salt marsh creeks by boat at low tide:

To float down in a canoe with the ebb tide, to explore the narrow channels now sunk deep below the marsh level, to surprise the marsh birds on the broad sand and mud flats, to push over the waving forests of eel grass and their varied inhabitants, affrds much enjoyment, and opens up an entirely different world from that of the same water courses when they are brimming over onto the marsh. Partly from prejudice, partly from ignorance, dead low tide is not appreciated as it deserves. The clean sand of the estuaries and the fine mud of the smaller creeks and inlets, and the clear water of the sea, are all very different from the foulness to be found at low tide in the neighborhood of sewer-discharging cities.

For the reader of today, a clear theme throughout this book is the impact of humans upon nature, already underway in the 1910s and 1920s. Townsend notes the ongoing increase of invasive species, including beach wormwood (a plant), and the European periwinkle (a snail). He notes that deer numbers are up in the region, compared to their total absence in Thoreau’s day (1853), partly due to highly protective hunting laws in eastern Massachusetts, but also resulting from the extirpation of wolves, lynxes, panthers, and Indians from the region. Harbor seals, Townsend observes, are starting to return to the coast; until 1908, Massachusetts placed a bounty on them, intended as a boon to fishermen afraid of seals jeopardizing their livelihoods. Finally, there is mention of the impacts of the millinery trade on birds, specifically common terns:

Not so many years ago various fragments and the whole skins of these beautiful birds were fastened on women’s hats, just as scalps and feathers are fastened on the head-dresses of savages. Thousands of the birds were shot down where they could be most easily obtained. namely, on their breeding grounds, for they are plucky little birds and valiantly attack any marauder who intrudes on their homes, and they do not seek to escape. These, as well as other species of birds, were greatly reduced in numbes by this cold-hearted combination of fashion and slaughterers, when, through the strenuous efforts rof the Audubon Society ad of ther bird lovers, the killing was stayed, and, too the great joy of all naturalists, the graceful birds are again increasing.

Meanwhile, the situation for piping plovers and other shore birds remained grim. Consider the tragic fate of the immature sanderlings, who endure a barrage of guns every fall:

In the middle of August the young, sadly inexperienced, arrive, and in their tameness fall an easy prey to the gunner. They are beautiful birds, with faint smoky bands across their white breasts. It is a great pleasure to watch a flock as they crowd together along the shore, probing every spot of sand for the small molluscs and crustaceans which consti- tute their food. As the season advances our pleasure is somewhat dimmed by the fact that cripples, with a foot shot away or blood-stained sides, are common in their ranks.

The piping plovers, another shorebird species, are on the path to extinction:

Up to half a dozen years ago the piping plover bred regularly in the dunes and laid its eggs in the sand. It belongs to a dying race, and although it is protected by law at all seasons, I fear this is not sufficient to stop its path to extinction. So long as the law permits the shooting of other plovers of the same size and the small sandpipers, one cannot expect the ordinary gunner to discriminate, as in fact he is unable to do, and the piping plover is shot with the rest. Only by stopping all shooting, or by the creation of bird refuges, can the tendency to extinction of this and other shore birds be prevented.

The 1925 “New Edition” of this book (which I read) adds a hopeful footnote: “The passage of the Federal Migratory Bird Act has since stopped the shooting of most of our shore birds.” Indeed, despite its grim moments (for instance, disparaging “these degenerate times” for all the wanton shooting of wildlife), even the first edition of 1913 manages to strike a somewhat hopeful note, at least in regards to seabird protection:

What a joy it would be to have a return of the old conditions, when terns and piping plover bred in the dunes, and when shore birds large and small thronged the beaches, and when the sea teemed with water fowl. Many of the birds I have mentioned in this chapter are on the way to extinction, some have already disappeared forever; a few, happily as a result of protection, are increasing. In Japan it is said that when travelling artisans see an eagle, they take out their sketching tablets and record its beautiful shape and attitudes. The barbarians of this part of the world try to shoot it, a fate they have often meted out to every large or unusual bird they came across, even if it were of no value to them, and they left it to rot where it fell. Fortunately times are changing and the people are gradually awakening to the idea that money value in food or plumage, or even in work done for man, is not the only thing for which birds should be protected. We are also beginning to realize that the interest which finds pleasure in the sport of bird destruction is a very limited and a very selfish one, and that the claims of the sportsman are not paramount to those of the nature student or even of the lover of natural beauty.