I permitted my eyes to scan the tiny patch of bare ground at my feet, and what I observed during a very few moments suggested the present article as a good piece of missionary work in the cause of nature, and a suggestive tribute to the glory of the commonplace.

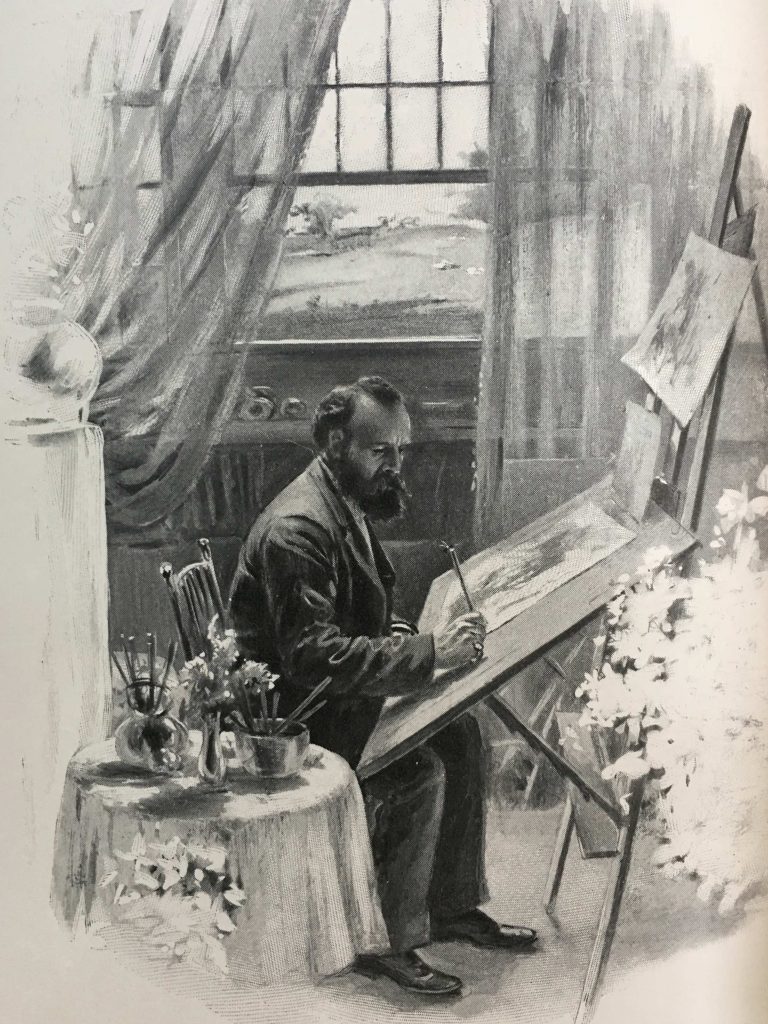

IN MY OPINION, W. HAMILTON GIBSON WAS THE MOST INSPIRING OF THE FORGOTTEN NATURALISTS FROM THE GENERATION AFTER THOREAU. Nowadays, he claims a Wiki page and little else, though scanned copies of his books are easily obtained from online archives, along with his biography (even more forgotten) from 1901. Gibson was an amazingly talented artist and natural scientist, who harnessed those two interests to craft highly engaging vignettes revealing mysteries of the everyday world around his summer art studio in Washington, Connecticut. Even the most dull bit of bare earth held its share of secrets to him, and he worked wonders with flowers, teasing out the complex interplay of flower structure and pollinator species. “Pluck the first flower that you meet in your stroll to-morrow,” he wrote, “and it will tell you a new story.”

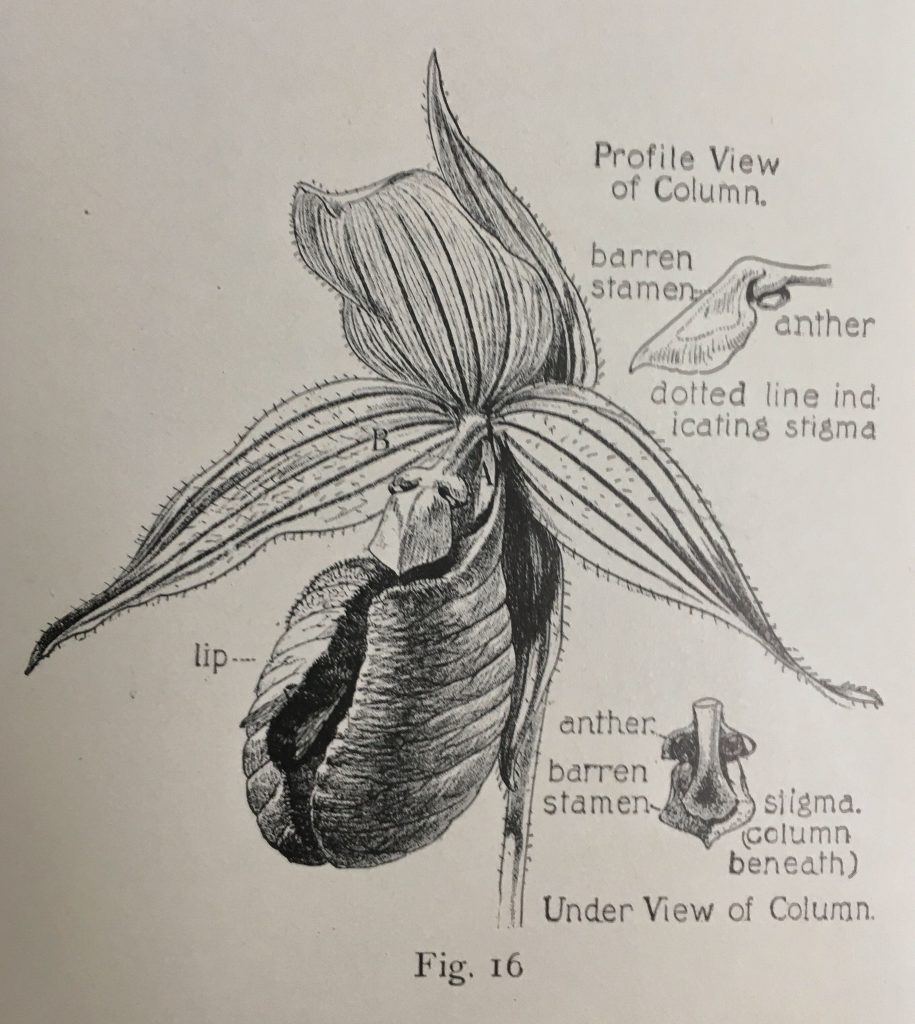

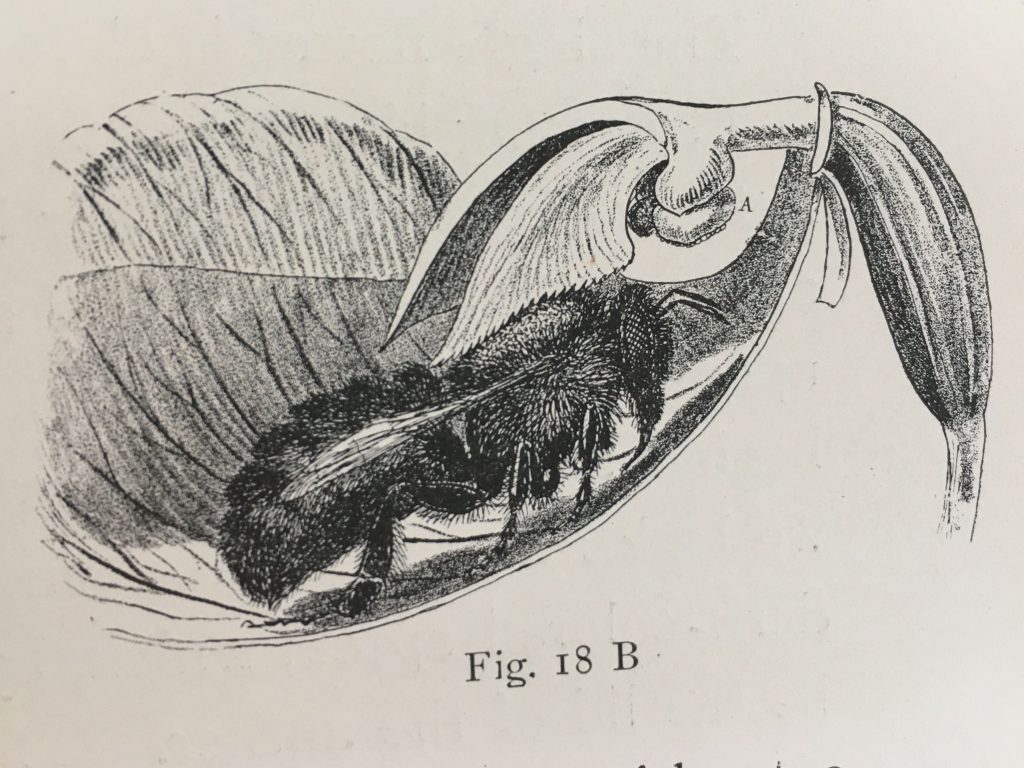

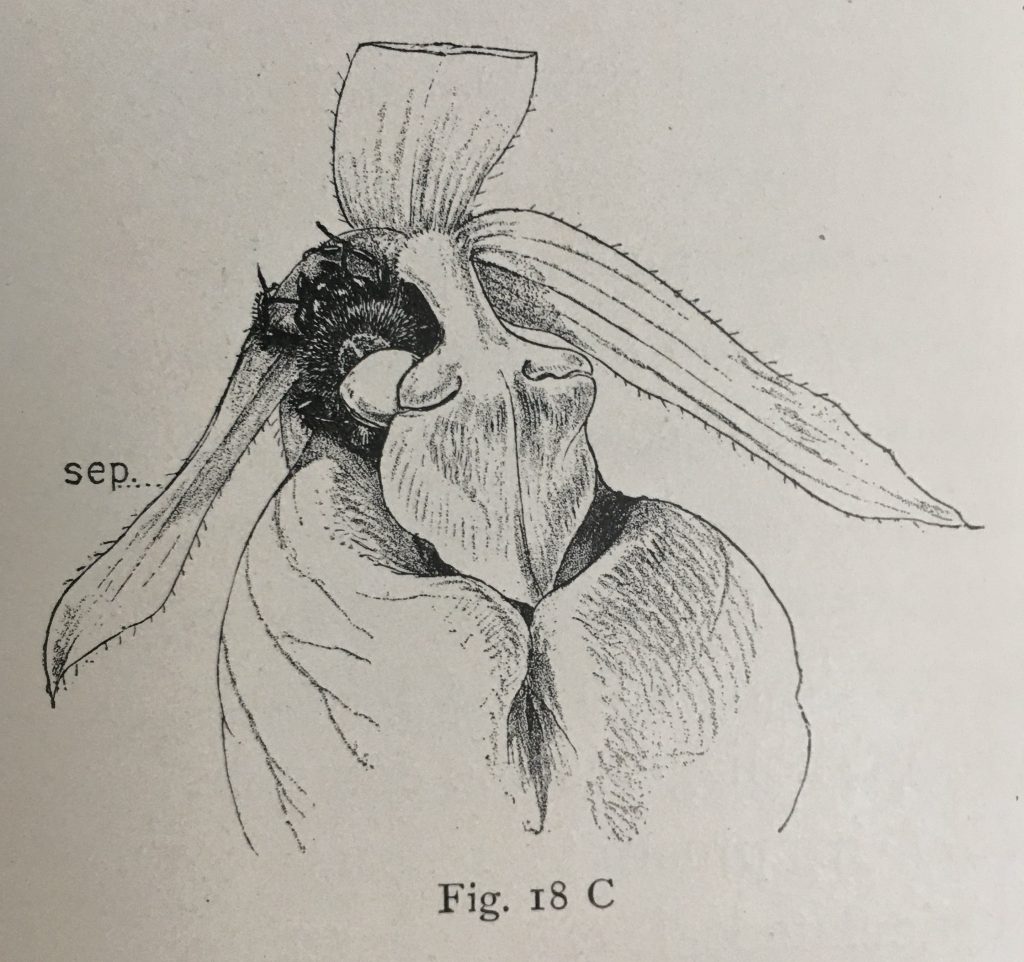

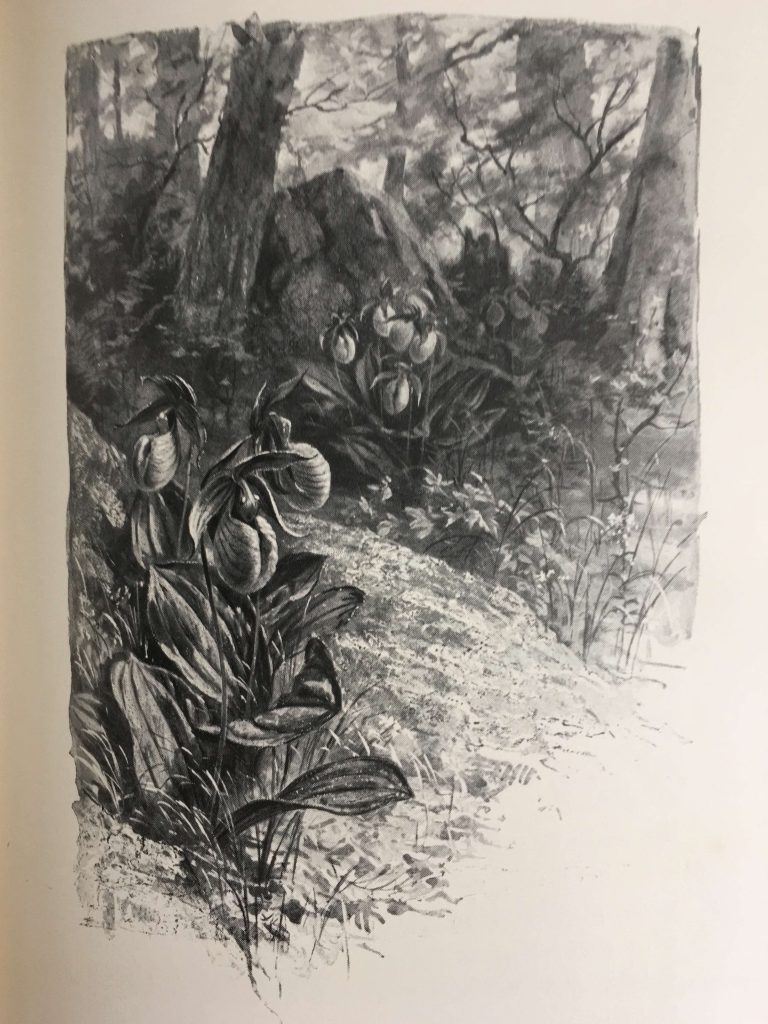

GIBSON LIVED A TRAGICALLY BRIEF LIFE, DYING OF A STROKE BROUGHT ON BY OVERWORK AT THE AGE OF 46. “My Studio Neighbors” was published posthumously. As such, it does not have the coherence of his more polished works (which I will read and report upon at a later date). Instead, it is composed of several essays about insects and their fascinating (and somewhat macabre) stories well-crafted to engage the general reader, and several botanical essays on flowers and their pollinators that seem pitched to a more scientific crowd. I suspect he may have had a book in mind, or possibly even two. I learned quite a bit from his botanical pieces about pollination; for instance, I did not know that all orchids are characterized by having both anther and stigma (male and female reproductive parts) on the same stalk, known as a column. I also found fascinating how he went about figuring out what pollinated each flower, sometimes by observation, sometimes by deduction, and sometimes by forcing an insect such as a bumblebee to enter a flower to pollinate it. He accompanies his explanations by drawings that indicate stages if a process. In the drawings below, a bumblebee is making her way out of a Cyprepedium orchid (left), a process that requires getting doused with pollen (center) before being able to force her way out through the top (right).

MY FAVORITE ESSAYS FROM THIS BOOK, THOUGH, EXPLORED BACKYARD NATURE MYSTERIES. Gibson was an engaging storyteller: he we describe the what he saw, then explain carefully to the reader how he went about solving the puzzle as to what was actually going on. His stories focus on everyday things, and in doing so, they have the effect of inspiring the reader to find similar wonders close to home. He opens his essay Doorstep Neighbors with this exhortation:

How little do we appreciate our opportunities for natural observation! Even under the most discouraging and commonplace environment, what a neglected harvest! A backyard city grass-plot, forsooth, what an invitation!

After these enthusiastic words, Gibson gets to work setting the stage for his tale:

The arena of the events which I am about to describe and picture comprised a spot of almost bare earth less than one yard square, which lay at the base of the stone step to my studio door in the country.

Against this humble backdrop, Gibson proceeds to share about the many holes he finds there, and the wandering insects that suddenly disappear into them. Clearly, there is a whole lot going on. Not content merely to watch, Gibson consigns a couple of victims to their fate:

A poor unfortunate green caterpillar, which, with a very little forcible persuasion in the interest of science, was induced to take a short-cut across this nice clean space of earth to the clover beyond, was the next martyr to my passion for original observation. He might have pursued his even course across the area unharmed, but he…persisted in trespassing, and suddenly was seen to transform from a slow creeping laggard into the liveliest acrobat, as he stood on his head and apparently dived precipitately into the hole which suddenly appeared beneath him.

Gibson continues his bemused explorations, trying to cover up the holes and the watching them cleared of debris as if by magic. Finally, using a long blade of Timothy grass as a fishing pole equivalent, Gibson inserted it into one of holes. A beetle grub lurking at the bottom (10 inches down) snapped at the grass and was brought to the surface for inspection. But this did not solve all of the mysteries, because meanwhile other holes were being excavated by various wasps, who would fly away only to reappear dragging the body of a spider or a caterpillar. This, too, let to some fascinating research using everyday materials:

Constructing a tiny pair of balances with a dead grass stalk, thread, and two disks of paper, I weighed the wasp, using small square pieces of paper of equal size as my weights. I found that the wasp exactly balanced four of the pieces. Removing the wasp and substituting the caterpillar, I proceeded to add piece after piece of the paper squares until I had reached a total of twenty-eight, or seven times the number required by the wasp, before the scales balanced. Similar experiments with the tiny black wasp and its spider victim showed precisely the same proportion….

IF I WERE GOING TO USE ONE WORD TO DESCRIBE GIBSON’S WORK, I THINK ‘CHARMING’ WOULD DO THE JOB WELL. Gibson would have been a delightful person to meet and talk with at length — though in my case, I fear we would soon get stuck on the topic of how overwhelmed we our by our respective work obligations. He never quite took himself too seriously, avoiding the pontificating that Blatchley sometimes fell prey to. He was both a highly talented artist and a keen naturalist, and I will undoubtedly write more of him and his other books in the future.

FINALLY, A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE COPY I READ. My copy is likely a second edition, published in 1898. A bit stained and weatherbeaten, it is still in fine fettle, with the binding in excellent condition. The outstanding feature of the book (apart, of course, from Gibson’s drawings and writings) is the spectacular cover. A ring of butterflies encircles the book title, against a background of olive green cloth. As for its history, all I have in this regard is a tiny stamp glued to the upper left corner of the inside of the front cover, with the name Amelia Stevenson printed on it.