One of my first sights, upon entering a patch of woods adjacent to the wetlands at Newman Wetlands Center, was of an adult five-lined skink (Plestiodon fasciatus), a common species of lizard that is quite abundant on our back patio this time of year.

Along the first stretch of boardwalk, I encountered this red ant resting on the railing.

Continuing down the same stretch of boardwalk, I found a popular trailside perching area for Blue Dashers (Pachydiplax longipennis), a dragonfly species common in the Eastern United States.

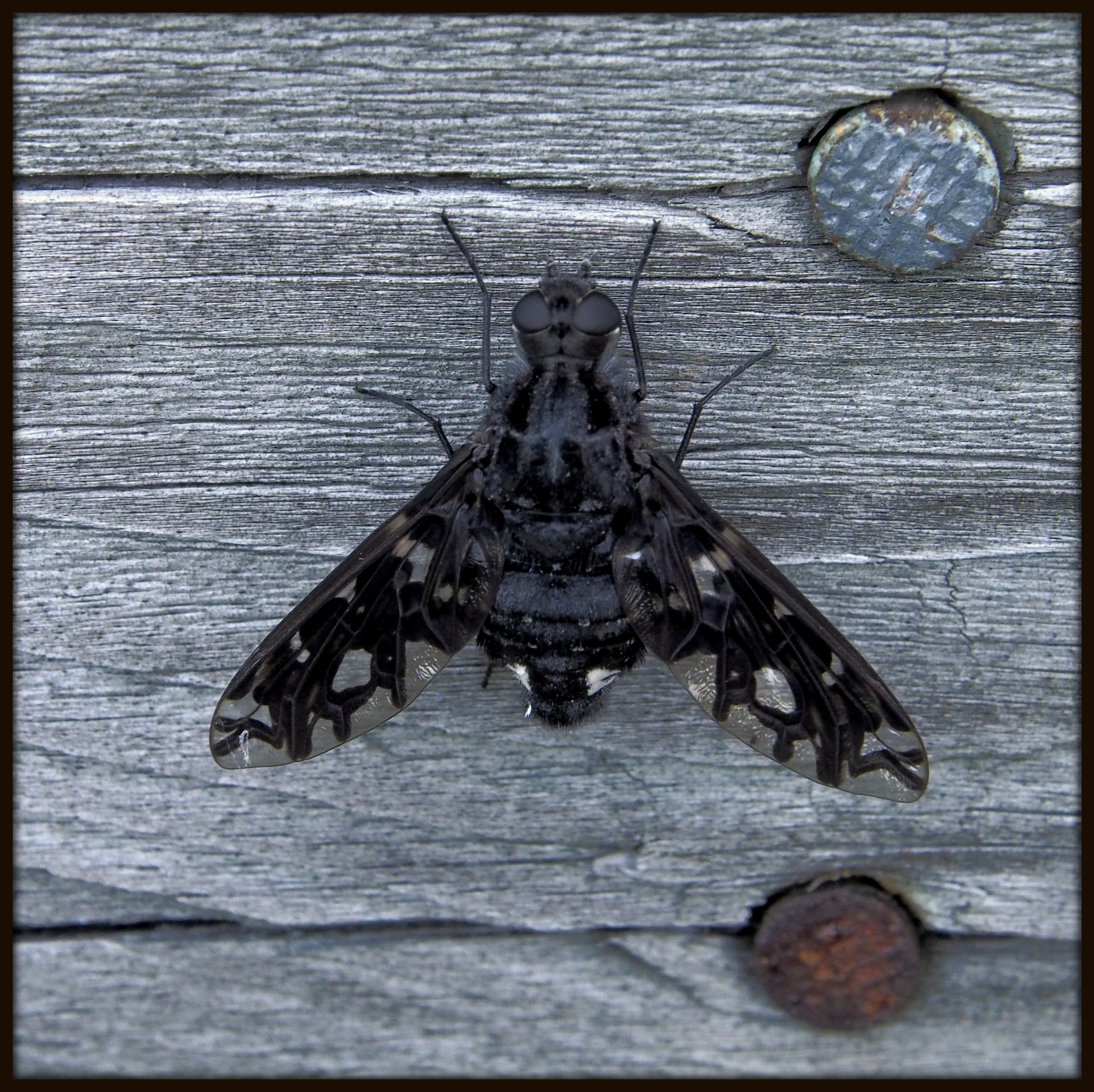

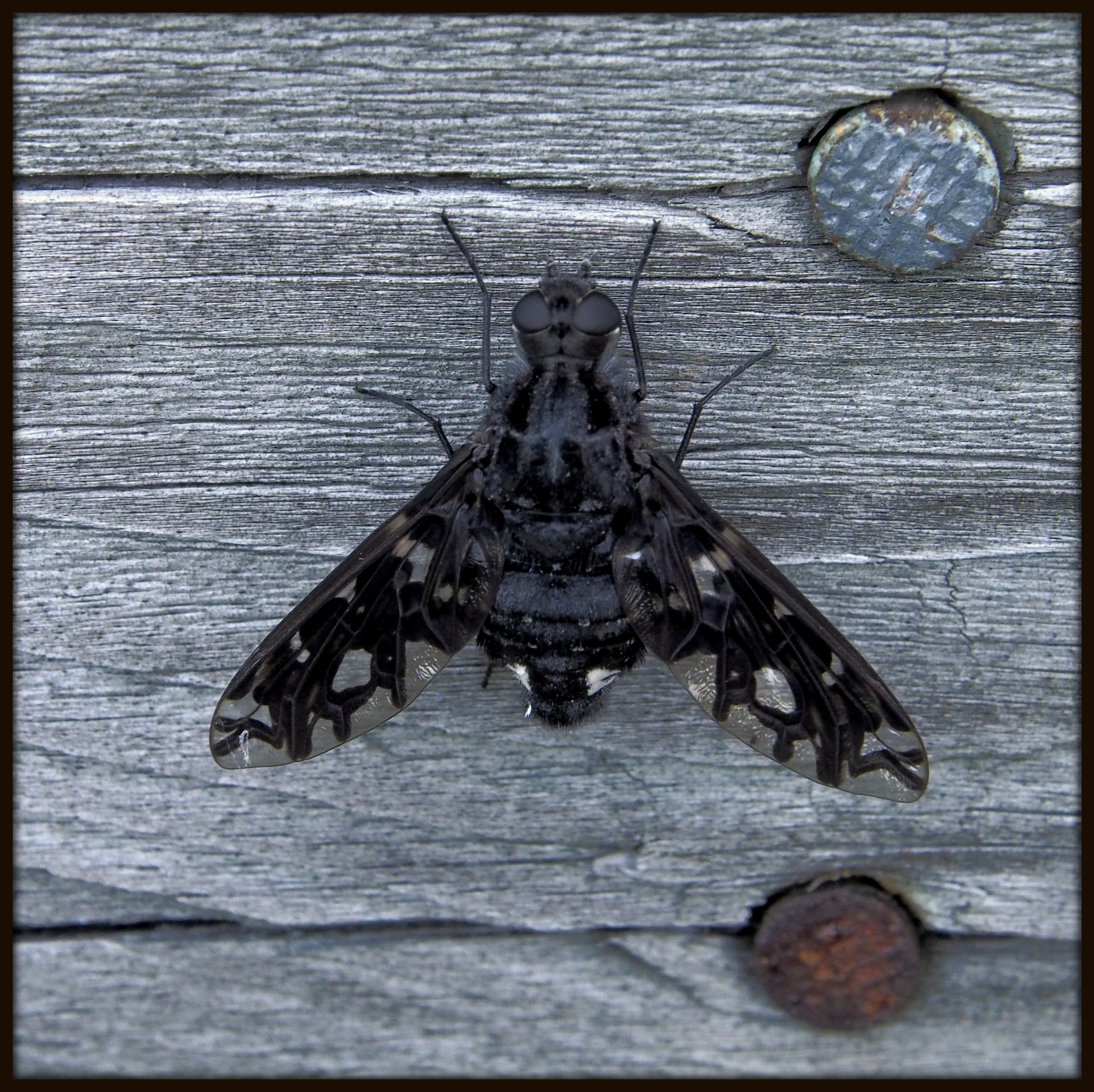

I try to be an equal-opportunity photographer, including a mix of good, bad, and ugly. When it comes to flies, though, I often hesitate. I am proud to say that I photographed this fly and added it to this blog, all the time thinking it was a vicious deer fly. Now I have to revise my opinion of this creature. According to folks at BugGuide on Facebook, it is actually a member of the family Bombyliidae, or bee flies. It is quite possibly Xenox tigrinus, or another member of that genus.

Further along, my next discovery was of another Blue Dasher willing to be photographed (the dragonflies were everywhere, but most darted too quickly from spot to spot, and/or had perches that were out of my camera’s macro range). This is my favorite dragonfly portrait of this particular outing. But I will be back again soon.

Stepping onto terra firma once again, we immediately saw this female Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) in the path ahead. Valerie estimates her age at 75 to 100 years, and suspects that she may have been in search of a suitable location for laying eggs.

A short side spur led up the ridge, gaining about twenty feet in elevation and offering a view out over the wetland. In a tree hollow near the top, I glimpsed this insect, which was reluctant to be photographed. It is probably a Brown Lacewing (family Hermerobiidae).

After so many photographs of insects (particularly dozens of dragonfly shots, nearly all Blue Dashers), I paused to take a couple of wetland plant photographs. The first one, I admit, I took because of all the Least Skippers feeding on it. The white globe of tiny flowers turns out to belong to the Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis). Now that I have a name for the flower, and appreciate how unusual it is, I ought to go back and photograph it properly!

At last, a photograph simply in appreciation of the late afternoon sunlight shining through the underside of a leaf — in this instance, Common Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia).

On one such Arrowleaf, an Ebony Jewelwing damselfly (Calopteryx maculata) was perched. Although these damselflies are often quite timid, this one allowed me to get quite close with my macro lens.

On a couple of occasions, the damselfly opened its wings for just a moment. I caught this once, but my 1/30-second exposure was too slow to avoid some blur to the wings.

Nearing trails’ end, I paused to enjoy the reflection of wetland plants and dead branches in a pool.

Just before the final section of boardwalk on the main loop trail, I saw an Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)doing a bit of late-day feeding.

My ramble through Newman Wetlands took over two hours. In addition to the main loop, I also walked a few of the upland trails. There, wildlife was less abundant (or, at least, much less readily apparent). However, the sunlight through the trees afforded several stunning forest landscape photographs. These will be included in a Part Three post later today.

As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”

As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”