In 1891, Horace Lunt published what would be the last in a trio of nature books. The first, Across Lots (1888), was previously reviewed in this blog. The middle volume, As the Wild Bee Hums, appears to be available only through online archives. I return to an original volume of his work. In addition to obtaining a glimpse of his nature studies three years later, this process also resulted in online research that turned up a few more fragments of information about his life. More about that anon.

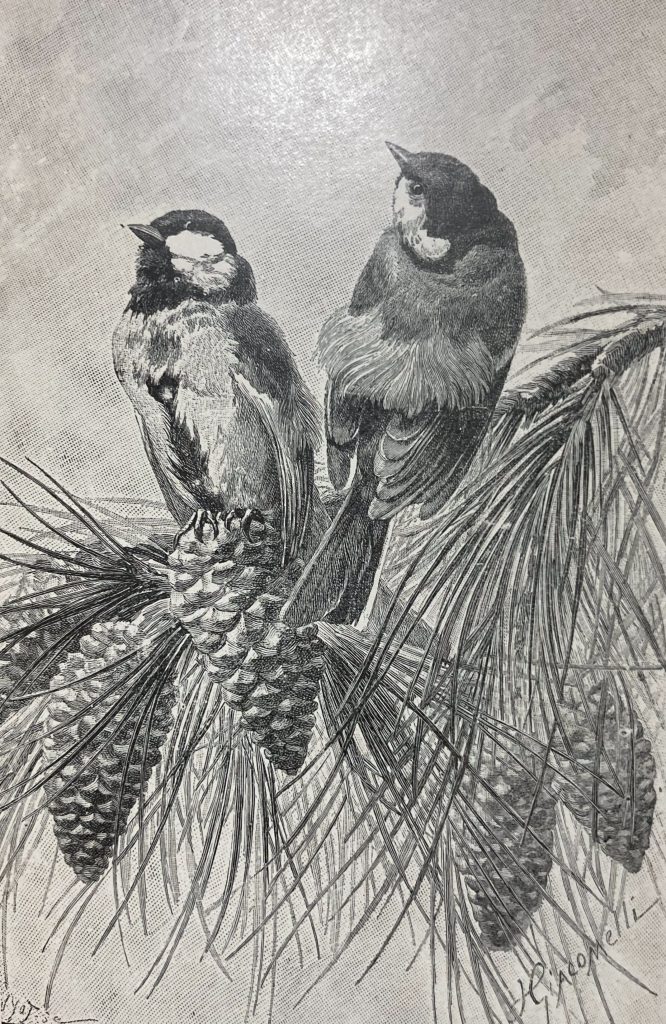

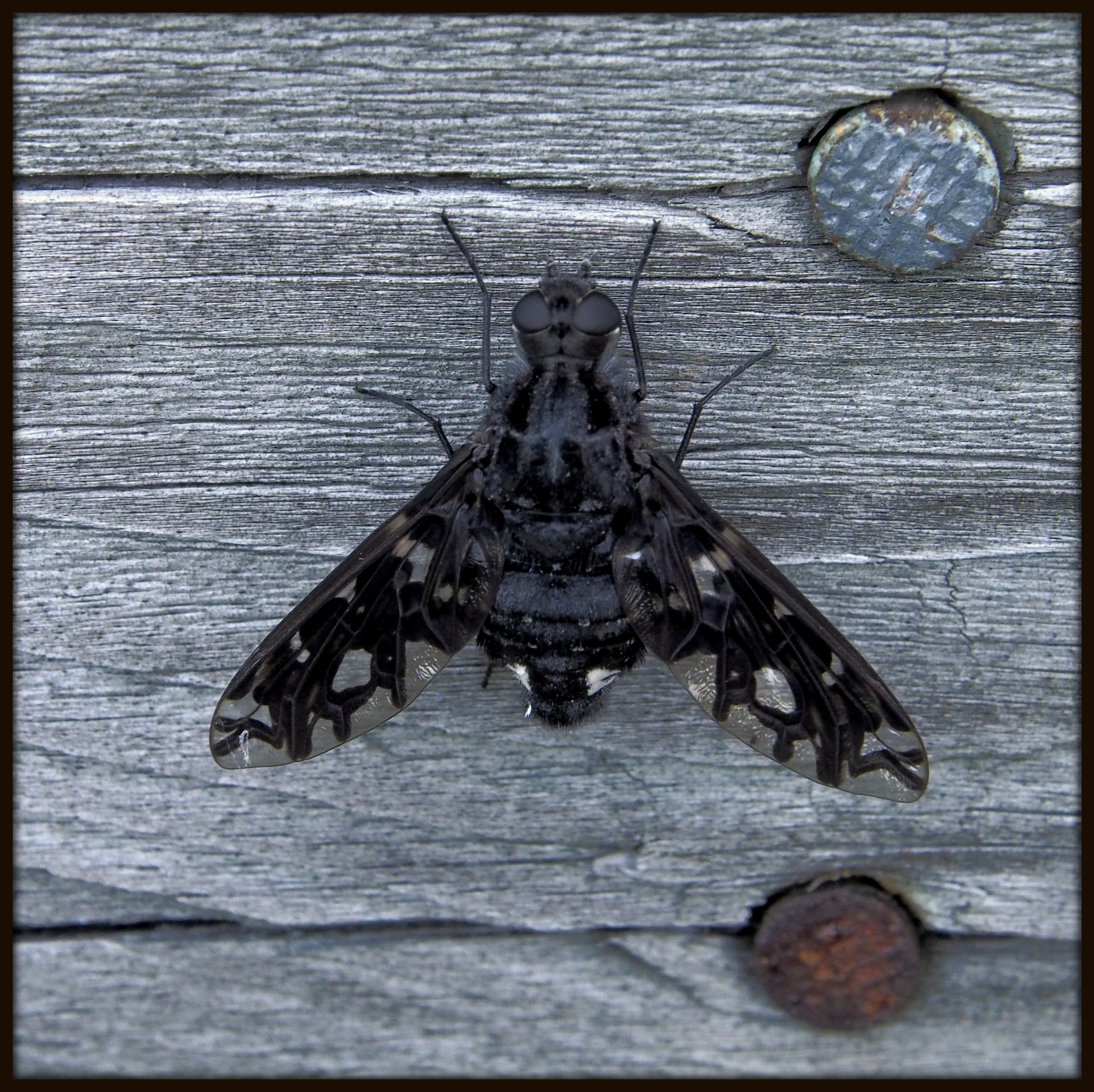

The publisher used the same decorative cover for this volume as is found on Across Lots. One suggestion that Lunt has “come up in the world” a bit as a writer since 1888 is that this volume has several black and white illustrations, most notably the pair of chickadees above. Another difference is that, while much of the book is filled with Lunt’s trademark nature rambles in New England over different seasons of the year, there are also several essays suggesting that Lunt has broadened his connections to other scientists, while also gaining scientific knowledge himself. In various parts of the book, Lunt writes about invertebrate life in ocean tidepools, diverse species of flies, lichens (considered plants at the time), and mosses. In each case, he makes certain to use the appropriate scientific terms; for lichens, those include apothecia, gonidia, thallus, and podetia. Unfortunately, the book’s illustrations are strictly decorative, and for the lichen novice, trying to grasp the nature of lichens without visuals strikes me as well nigh impossible. The same problem, unfortunately, is true of Lunt’s flies, tidepool life, and mosses. Lunt’s self-professed enthusiasm for nature is evident throughout; however, even robust (at times, bordering on eloquent) descriptive text is insufficient to convey many of those natural wonders to his readers.

Lunt’s circle of correspondents and/or writers he has read appears to have expanded considerably over three years. Not surprisingly, he mentions Torrey, Burroughs, Darwin, and Thoreau. But he also mentions a “Mr. Minot” — Henry Davis Minot (1859-1890), a railway magnate and ornithologist with whom we will become better acquainted in a future post. He also mentions George B. Emerson (1797-1881), educator and President of the Boston Society of Natural History as well as the cousin of Ralph Waldo Emerson. His work, A Report on the Trees and Shrubs Growing Naturally in the Forests of Massachusetts (1846), has been identified by some scholars as marking the beginning of the American Conservation Movement due to its advocacy of wiser forest management practices. Lunt names a female correspondent, Corinne Hoyt Coleman, living in New Hampshire. Finally, Lunt also refers to a “Robinson”, but his steadfast refusal to offer a first name or other details ensures that person’s enduring anonymity.

Before I close my review of this book, I will share a couple of Lunt’s most noteworthy descriptive passages. This first is from a visit to the seaside in his essay, “By the Sea” (complete with an obligatory military simile):

To Norwood’s bluffs, or the long stretch of sandy beach, I go to study the wonders of the shore in detail, and to obtain a nearer view of the ocean’s wrinkled face. It has character — its face is sterner and more imposing and expressive than the face of an inland sea. It’s voice is “The eternal bass in nature’s anthem,” and its breath has a healthful savoriness, a briny flavor, as refreshing to the scent as the perfume of flowers is to the homeward-bound sea voyager.

The winds play with it till it becomes impatient and beats itself against the rocks. Its plastic lips are wrought into a thousand gnarls and convolutions, as they curl through the fissures and caverns, while its foamy tongues, licking the stony bluffs as they recede, leave behind them many pretty cascades that flow gently down the slopes, till the waters mingle again with the incoming waves.

As there are lulls in the wind on a breezy day, so at intervals, as if exhausted with its fury, the sea by the shore becomes suddenly almost calm. Only gurgling, purling sounds are heard for a minute or two, as the wavelets lap the edges of the rocks. But it is gathering strength for another onslaught. Far out, the seas are running high again. A long procession of them swell up from the waters and roll toward the shore at the rate of four hundred feet in thirty seconds. I watch the leader rising higher and concaving as it comes rapidly on. Its crest undulates and throws up streamers of spray, like the flying hairs on the mane of a galloping horse. Now the climax is reached. The sharp edge bends in graceful curves, tumbles over and breaks with dull, heavy roar, into a long line of foam, that shoots swiftly up the steep, shingly beach; then, as it retreats, rolls back a thousand stones, which, as they strike against each other, make a crackling, rattling sound, like the snapping of musket caps by a regiment of soldiers.

Finally, here are a couple of excerpts from Lunt’s encounter with the moss world in his “Winter Sketches”:

So these modest, unpretentious mosses are humbling fulfilling their mission on the earth. They are continually making new leaves, while the old leaves are converted into rich mld, from which in time will spring up an army of higher plants, with their flourish of trumpets and their flying colors. Here at the foot of a tree is a large clump of moss with finer leaves and the thickly matted stems more delicately spun. If a yard or two of yellowish green plush with long hirsute pile had been carelessly spread out and conformed to the general unevenness of the ground, it could hardly have been distinguished, at a distance, from this beautiful piece of Nature’s weaving. The numerous awl-shaped, strongly curved leaves are arranged only on one side of the stem, as if the heavy winds blowing constantly on them from one direction had bent them, like grass-blades in the meadows. From out this soft, mossy bed has grown a mimic forest of brownish-yellow stems or pedicels on which are attached tiny fruit-cups — cornucopiae, arched or bent over like bows. A month or two ago each one of these fruit-cases was completely sealed by a ring of cells growing between the rim of the orofice and cover, that the vessels might be impervious to the weather during the growth of the spores. As the cases ripened, the cells were ruptured and the covers thus dropped off, and the spores or moss seeds were poured out and sown by the Winter’s wind…

If the attentive, descriminating rambler accepts the invitation which these humble but cheerful plants offer, he will be surprised to know how many species will salute him, and impart to him the various entertaining lessons in moss lore during an ordinary woodland walk. Each kind takes him by the button, as it were, and talks to him privately of its special characters and peculiarities.

I am struggling here with the image of a carefree talking moss plant. I think I may prefer Lunt in his more martial moments.

Since my last blog on Horace Lunt, I learned a bit more about him. He was born in York, Maine, and became an orphan at age five. He and his brother Samuel were raised by their aunt and uncle in Kittery, Maine. Another new tidbit about his life was that he may have had a leg amputated following the Civil War. His interest in nature evidently predated the war. In addition to writing, Lunt also gave public speeches. He was found dead in Essex County, Massachusetts, in May 1911 at the age of 74.

My volume of Short Cuts and By-Paths is neither signed nor stamped.

This article and the photograph accompanying it are the fruits of a naturalist’s recent adventure at

This article and the photograph accompanying it are the fruits of a naturalist’s recent adventure at