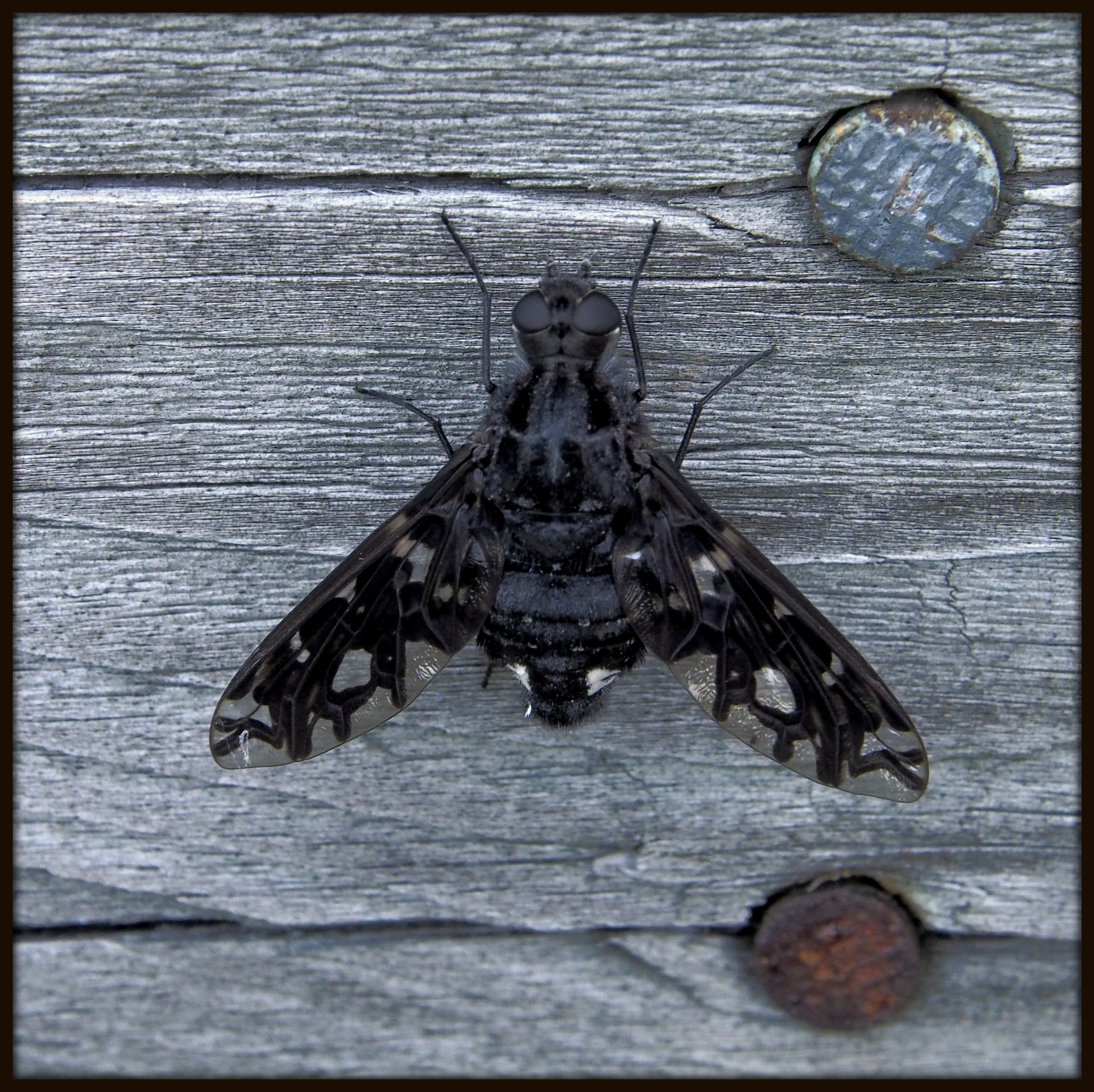

Tiger swallowtail butterfly. Photographed June 2011 at Newman Wetlands Center, Hampton, GA.

According to the book of Genesis in the Holy Bible, one of Adam’s first actions after being created was to gather together all living things and give them names. Clearly, the human predilection for classifying and naming plants and animals goes back thousands of years. It is most evident today in birders’ life lists: collections of scientific names of all the different birds one has seen over a lifetime. My own bookshelves overflow with field guides, nearly a hundred in all, covering birds, trees, salamanders, moths, mushrooms, and many other kinds of living things. In medieval alchemy, names had power to them, as shown by the fact that to spell refers both to stating the letters in a word and exerting magical influence in the world. Nowadays, to know the name (common or scientific) of a plant or animal is enough for a naturalist to find dozens of images and species accounts scattered across the Web. It is possible to take a digital photograph of a butterfly in the morning and spend the rest of the day indoors and online, reading about the butterfly, its life cycle, host plants, behaviors, etc.

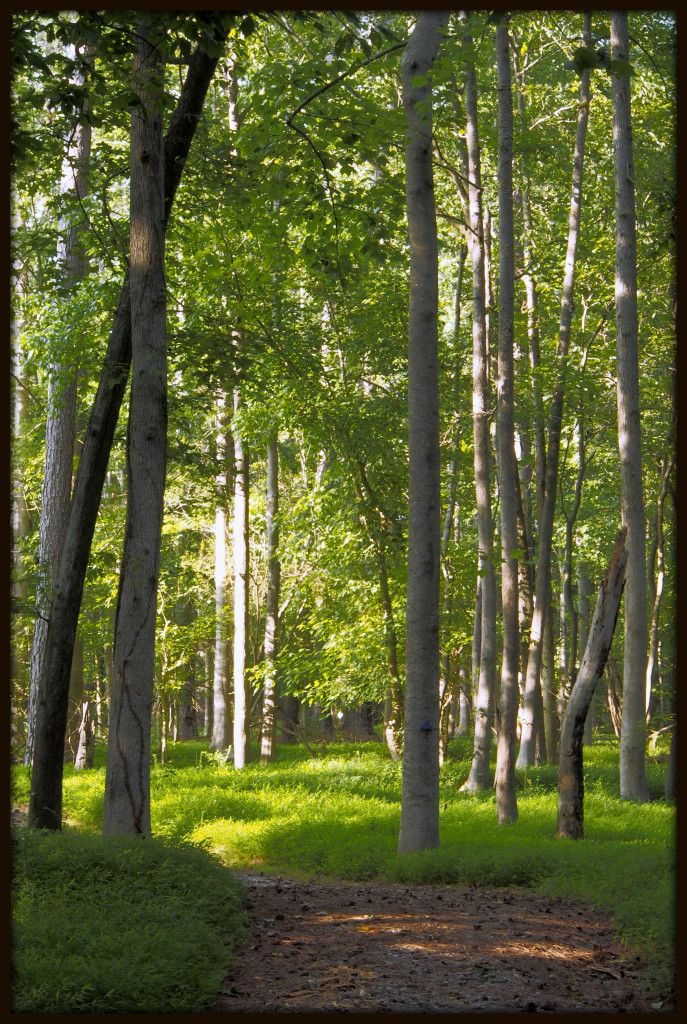

But naming is only one access point into learning about the natural world. And particularly for children, perhaps names are not the best place to start after all. The naturalist Barry Lopez warns, in his book of essays, Crossing Open Ground (pp. 150-151), “The quickest door to open in the woods for a child is the one that leads to the smallest room, by knowing the name each thing is called. The door that leads to a cathedral is marked by a hesitancy to speak at all, rather to encourage by example a sharpness of the senses.” Once we learn a name for something, there is a sense of completion, a suggestion that it is all that is necessary. Yet there is so much more out there to discover. When we take the time to study the more-than-human world closely, we begin to notice how trees and insects have individuality and personality of their own. A label just captures a static form, while living things are always changing. Caterpillars become butterflies, and a holly bush outside my window comes into bloom and suddenly swarms with bees and other flying insects craving nectar.

Thinking back to my own childhood (with many hours spent running barefoot across neighbors fields or tromping through a woodlot behind my house), I recall how few plants and animals I could identify. I knew what poison ivy looked like, and my brother taught me about jewelweed because it could be used to treat poison ivy. There was a shrub that grew in several places in the yard that I was confident was witch hazel; a few years ago, I learned that it was actually spicebush. There were dandelions, bane of my father, resident Lawnkeeper. And then there was Queen Anne’s lace, or wild carrot. My brother taught me that one, too. It’s roots tasted quite similar to carrot, but their texture was much closer to that of many strands of dental floss twisted together. In the front yard, there were black walnut trees that periodically covered the lawn with large green nuts, and in the far front, by the road, a stately sycamore that I learned in school was one of the oldest deciduous trees in the evolution of life on Earth. Animals I knew only by categories: ants, spiders, squirrels. My knowledge of classification was ad hoc and full of holes, having as much to do with uses plants could be put to as anything else.

I am in good company. Even the famous biologist E.O. Wilson recognized that this kind of nature experience may be more important in fostering a love of nature and sense of wonder about the environment around us. In his autobiography, Naturalist, he wrote (pp. 12-13) that “Hands-on experience at the critical time, not systematic knowledge, is what counts in the making of a naturalist. Better to be an untutored savage for a while, not to know the names or anatomical detail. Better to spend long stretches of time just searching and dreaming.” Wilson went on to quote Rachel Carson’s essay, The Sense of Wonder, in which she commented that “If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and the impressions of the senses are the fertile soil in which the seeds must grow. The years of childhood are the time to prepare the soil.”

How, then, to encourage children to connect with nature, if not by way of field guides? One approach would be simply to encourage children to go on backyard safaris, to see what they can discover and study it closely. All that is needed are long pants and repellant against ticks and chiggers, knowledge of how to avoid fire ants, poison ivy, and other hazards of going adventuring, a magnifying lens, perhaps a jar with holes in the lid, maybe even a digital camera, and plenty of time. I suspect the child will return with tales of sights and wonders you had not imagined before.

Another activity is to choose a few trees and shrubs, observe them closely with a child, and encourage him or her to give them names. Periodically over the seasons, the child can be encouraged to revisit Bendy Tree and Prickly Shrub. How are they changing day to day, and season to season? Are there new visitors to the tree that weren’t there before? Are the leaves just unfurling, or are they perhaps riddled with holes from someone’s latest meal? Eventually, as the child gets to know the plants better, and is on familiar terms with them, he or she may inquire after their scientific names (or at least their common ones). Then it will be time to break out a field guide. The name will add one more layer of knowledge to what is already there, rather than being sufficient by itself. There is so much about nature hidden beneath the names, like salamanders beneath cobbles in a stream, just waiting to be explored.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2012.

Last Saturday (the first day of Spring), a search for signs of spring took the author to

Last Saturday (the first day of Spring), a search for signs of spring took the author to