Well we know that the wild things manage their domestic affairs in a way best suited to their needs and natures. But it is only here and there than a human being can gain the confidence of the wild things so far as to share the secrets of their lives.

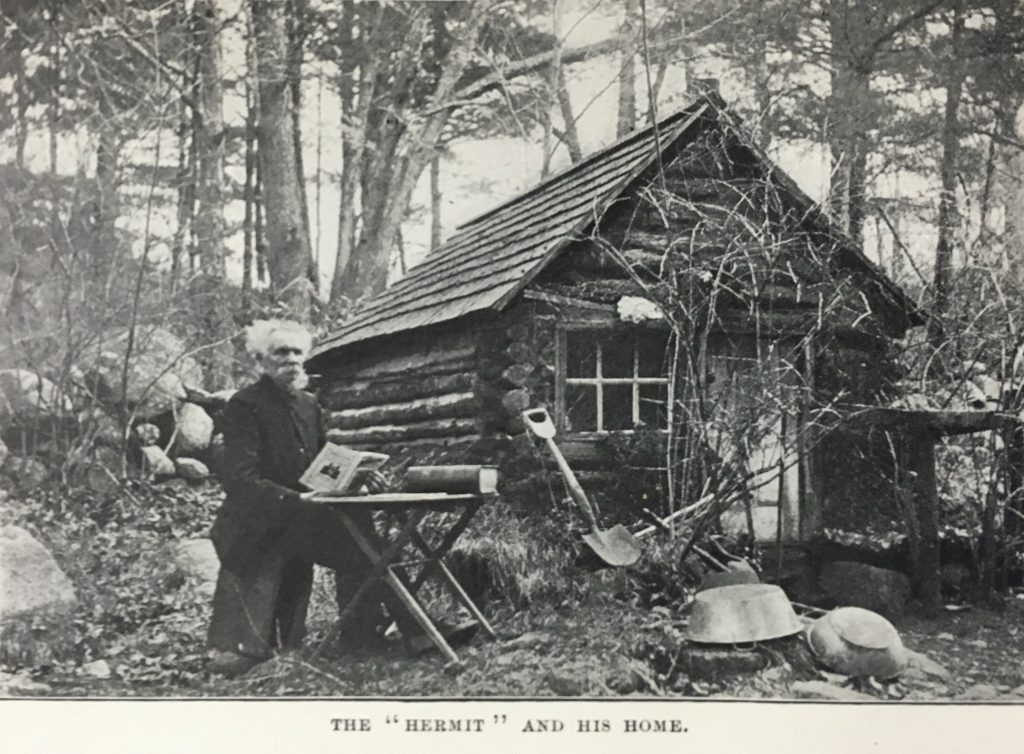

KNOWN TO HIS FANS AS THE HERMIT OF GLOUCESTER, MASON WALTON LIVED IN A CABIN IN THE WOODS OF CAPE ANN, MASSACHUSETTS. Born and raised in Maine, Mason came south for his health, hoping his various illnesses would be cured by some time at sea with the fishermen. When they all declined to take him aboard, he headed for a hill a short distance inland, set up his hammock, and began living out of doors. Within a few months, he had constructed his first cabin; a few years later, he built a second one. For eighteen years, he spent his days observing nature, and particularly the birds and small mammals that lived around (and even in) his rustic home. Even with his cabin sanctuary, he still spent eight months of every year sleeping outside in the hammock He made his living as a writer of columns in Field & Stream, a project that earned him many admirers. For a time, he grew flowers and sold them for supplemental money. He kept notebooks of all his interactions with “the wild things”, as he called them, and drew upon his notes to write a series of essays cobbled together in a volume published in 1908. It was his only book; he abandoned his hermit life a few years later, and passed away in his sleep in 1917, at the age of 79.

TO A CONSIDERABLE EXTENT, HOWEVER, HIS PERSONA OF A FOREST HERMIT WAS A MANUFACTURED ONE. He frequently had visitors to his home, sometimes even crowds. Though he remained unmarried (his only wife and child had died tragically when he was still young, before he moved to Cape Ann), he certainly did not want for friends and associates. Most humorously of all, though, was his daily coffee habit, which sounds frightfully like a modern-day Starbucks addiction many of us might confess to:

I found it inconvenient to cook my breakfast and then, after eating it, go to the city [Gloucester]. Why I did so was on account of my coffee habit. I had tried to find a good cup of coffee in the city and had failed, so had depended on my own brewing.

One morning I dropped into the little store at the head of Pavilion Beach, and the proprietor asked me to have a cup of coffee. He piloted me into the back shop, where he told me that he served a light lunch with coffee, to the farmers. The coffee was just to my taste, and for twelve years I patronized the coffee trade in that little back shop. My note-book shows that during the twelve years I had missed only eighty mornings. I had paid six hundred and forty-five dollars, during that time, for my lunch and coffee, and had walked, on account of my breakfast, seventeen thousand two hundred miles. Whew! It makes me feel poor and tired to recall it.

I CONFESS THAT I AM A BIT HARD-PRESSED TO CONSIDER HIM A HERMIT AFTER READING THIS PASSAGE. It is almost like a parody of Thoreau’s chapter on Economy in “Walden”. where Thoreau carefully considered his various expenses in setting up his cabin, which totaled just over twenty-five dollars. To put his expense into modern terms, using an online inflation calculator I was able to determine that his coffee habit cost him the 2020 equivalent of over $18,000. (To be fair, Thoreau’s 2020 expenses would be over $850.) Then I remind myself that Walton slept out-of doors from the first of April through Christmas, and that ought to count for something.

WALTON, AN AMATEUR NATURALIST, WAS KEENLY OBSERVANT OF THE BEHAVIORS OF LOCAL WILDLIFE. Unlike the modern ecologist, though, Walton was more than willing to interact with the wildlife, and learn from those cross-species communications. He regularly fed birds and squirrels and mice, keeping a loaf of bread in a caged box just outside his cabin door and regularly scattering anything from seeds and corn to cupcakes and donuts for his wild friends. While he maintained the noble attitude that they were his teachers, he did not always make the kindest of pupils. His very first story in the book, about a raccoon named Satan, begins with him catching the raccoon in a trap and chaining it to a tree in his front yard. Once, when upset about Satan’s running up a pine tree and being difficult to retrieve, Walton whipped the raccoon to teach it a lesson. And while he was generally quite kind to birds, he regularly killed crows, snakes, and weasels, all of which he saw as threats to the local songbirds. (Once he did keep a garter snake as a pet for a few months, but the weather turned colder and it died.)

ONCE WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE HERMIT OF GLOUCESTER’S VARIOUS IMPERFECTIONS, THOUGH, THERE REMAINS A CONSERVATIONIST SIDE TO HIM THAT IS WORTH RECOGNIZING AND APPRECIATING. To his credit, for instance, Walton gave up his gun in favor of respecting (nearly all) wildlife he encountered. And he was quite dedicated as a student of wild creatures. This is how he described his work, in an essay about a red squirrel he named Tiny:

I am writing natural history just as I find it, from observation of the wild things. To some of these wild things I am caterer, protector, and friend. They do not object to my presence when engaged in domestic affairs, so my ability to pry into their secrets is increased in ratio to the confidence accorded me.

Walton noted, on more than one occasion, that too many naturalists of the time simply echoed what they read about in books, rather than closely studying nature themselves:

With few exceptions, writer on outdoor life make it a point to denounce the red squirrel. They claim that he is a nest-robber of the worst kind. The most of this abuse bears the earmarks of the library. One author copies after another, without knowledge of the real life of one of the most interesting wild things of the woods.

Perhaps Walton’s most fascinating discovery, from all his observations, pertained to the white-footed mice that took possession of his cabin:

My object in writing about these mice is to call attention to their peculiar method of communication. I have summered and wintered them over fifteen years, and never have I heard one of them utter a vocal sound. They communicate with each other by drumming with their fore feet, or, rather, they drum with their toes, for the foot in the act is held rigid while the toes move.

If any writer has called attention to this…, it has escaped my reading. I am well satisfied that the habit has never been published before, so it must prove interesting to those who pry into the secrets of Dame Nature.

Curious, I investigated current scientific knowledge on the subject. According to the University of Georgia Museum of Natural History, the mice communicate by foot-stamping, vocal squeaks, and scent.

ONE FASCINATING THING I LEARNED ABOUT WALTON WAS THAT HE WAS, IN FACT, A FRIEND OF THE NATURE WRITER FRANK BOLLES, WHOSE THREE VOLUMES I READ AND WROTE ABOUT PREVIOUSLY IN THIS BLOG. Indeed, Bolles visited him at his cabin, and reported on the visit in his posthumously-published book, “From Blomidon to Smoky”:

I have a friend who lives alone, summer and winter, in a tiny hut amid the woods. The doctors told him he must die, so he escaped from them to nature, made his peace with her, and regained his health. To the wild creatures of the pasture, the oak woods, and the swamps, he is no longer a man, but a faun; he is one of their own kind, — shy, alert, silent. They, having learned to trust him, have come a little nearer to men…. The secret of my friend’s friendship with these birds was that, by living together, each had, by degrees, learned to know the other.

IN MARCH, 1903, JOHN BURROUGHS PUBLISHED AN ESSAY ENTITLED REAL AND SHAM NATURAL HISTORY, TOUCHING OFF WHAT CAME TO BE KNOWN AS “THE NATURE FAKERS CONTROVERSY”. Burroughs called attention to, and attacked, nature writers of the time who had taken to teaching children about wildlife by telling animal’s life stories from the animals’ own points of view. Although supposedly drawing upon actual observations, the accounts were simultaneously fictionalized, and they sometimes portrayed the animals as having very human thoughts and emotions. They threatened to blur the boundary between natural history and fantasy tales. It is no surprise that, in publishing his book about wild animals he befriended, Walton was very clear that he was a scientific observer, not a fiction author: “…the truth is that I describe wild life just as I find it, not as some books say I ought to find it.” In his finest moments as interpreter of animal thought and behavior, Walton is worthy of some degree, at least, of admiration and respect. I know that I would gladly join him for a cup of coffee and some conversation if I could.

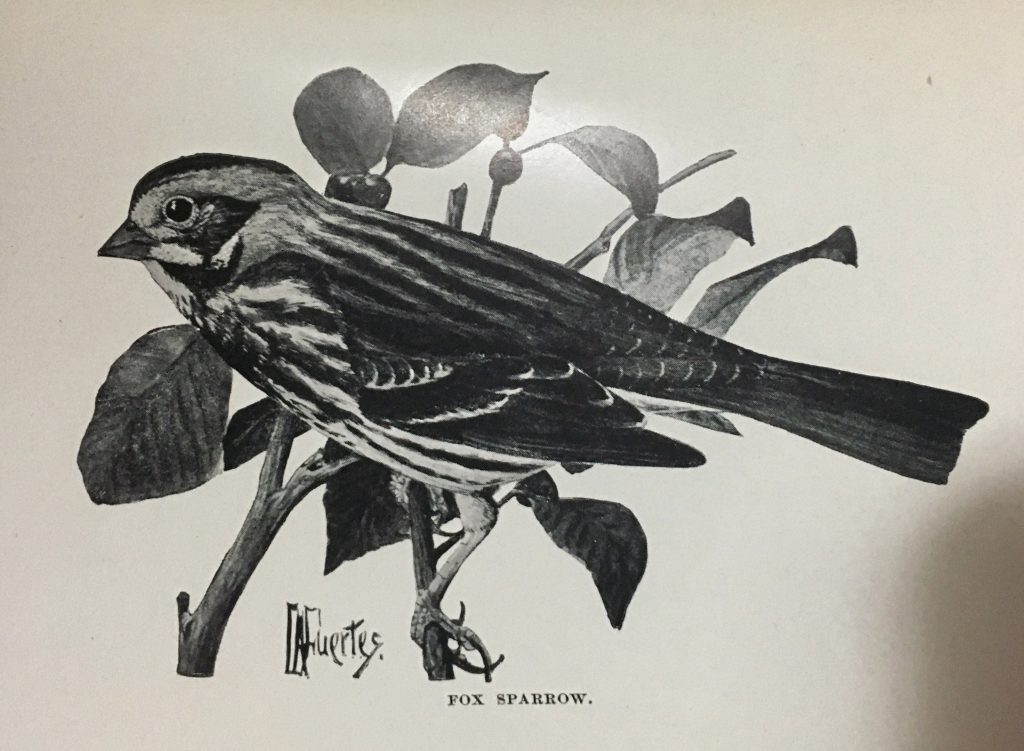

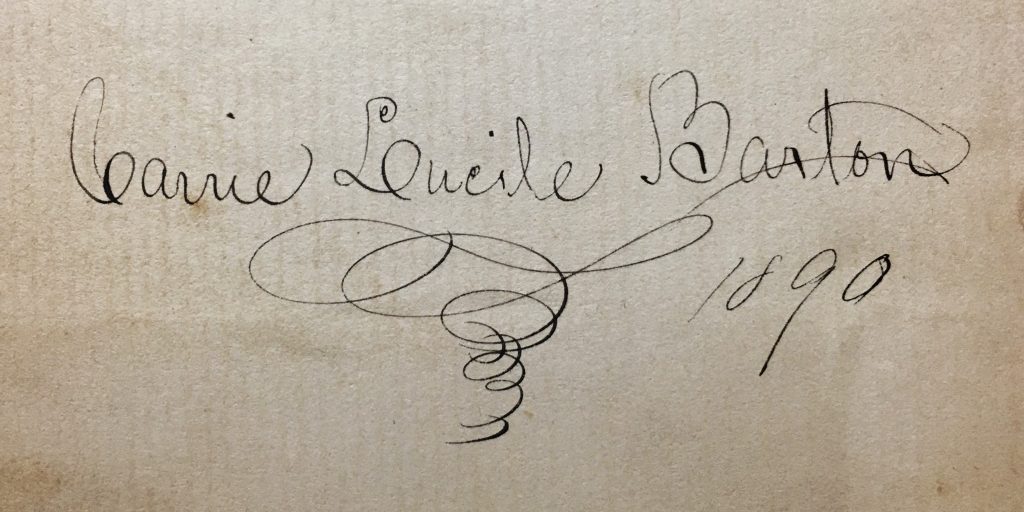

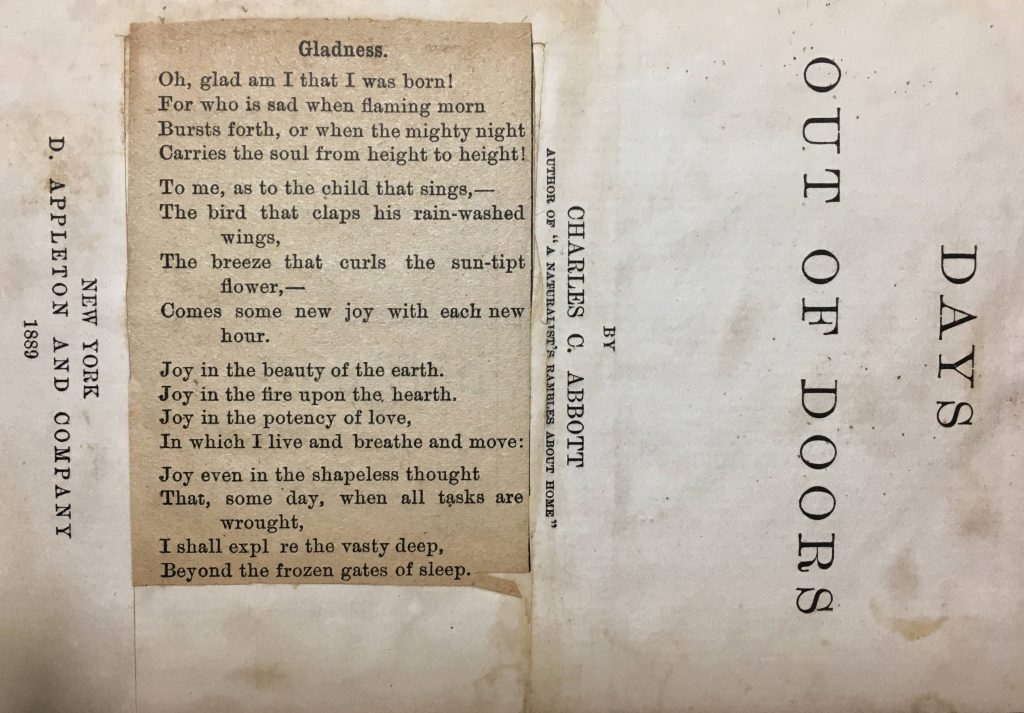

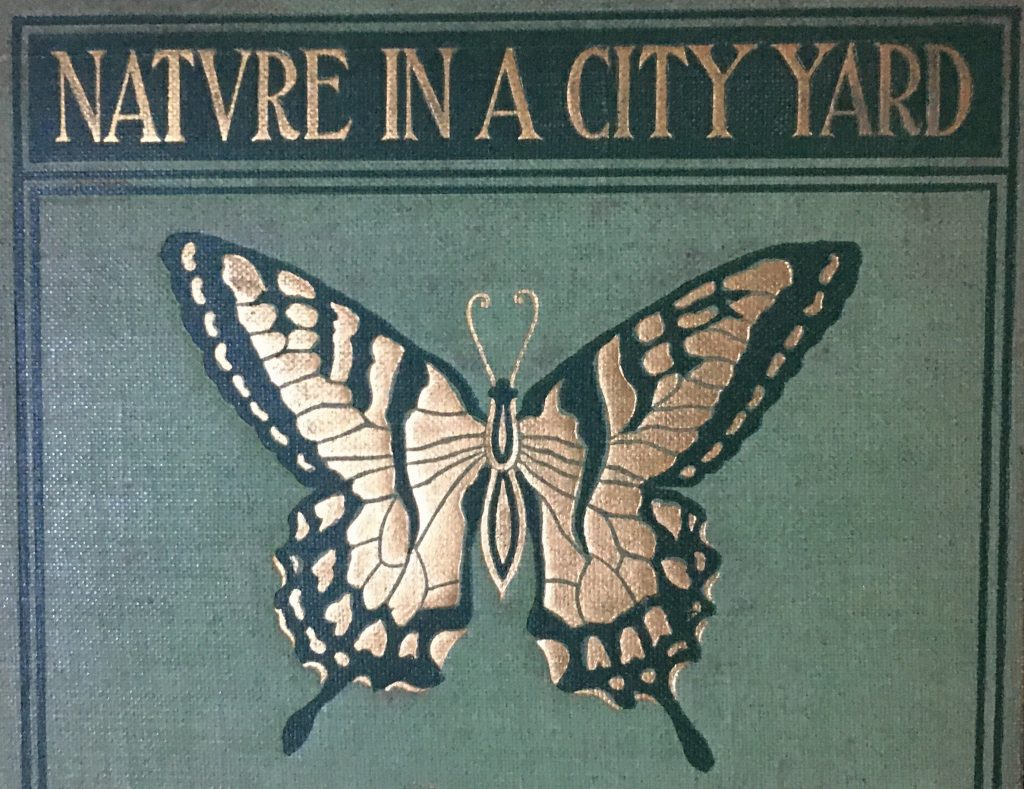

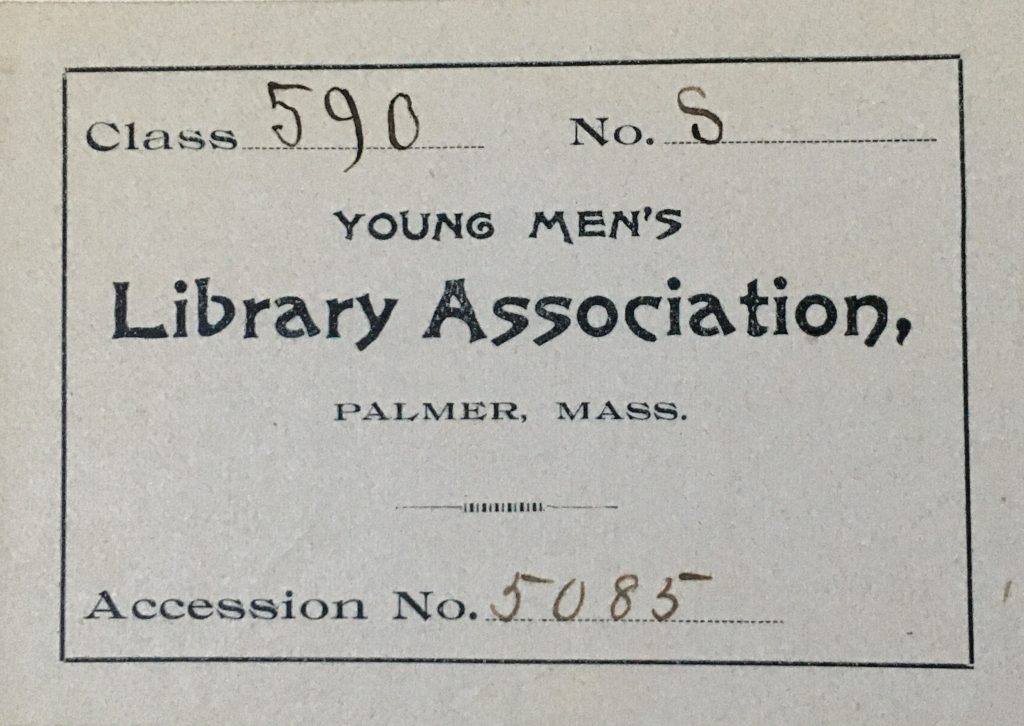

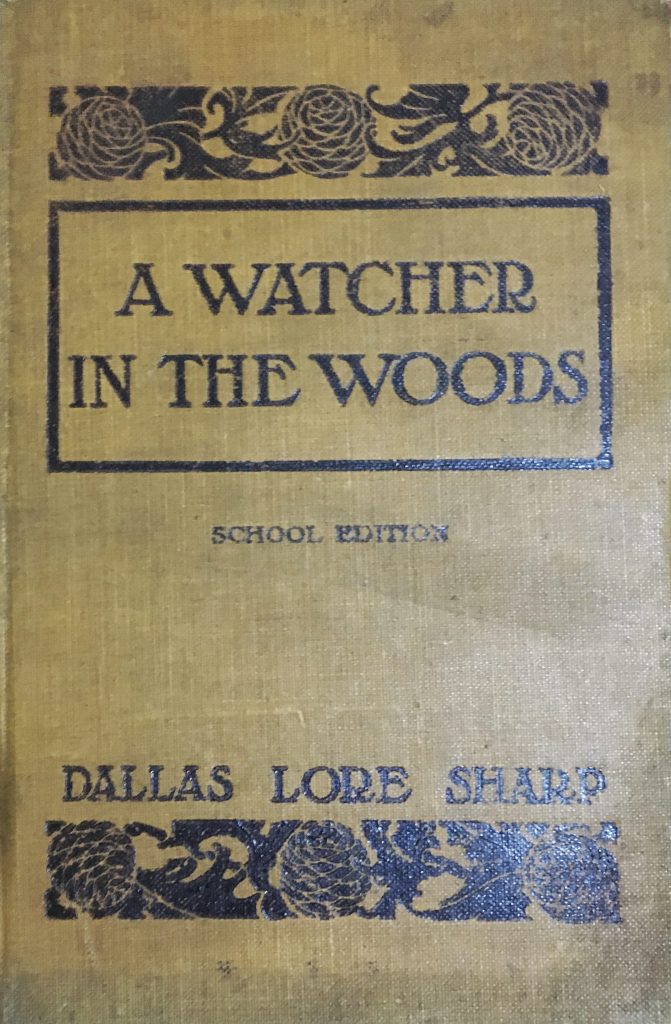

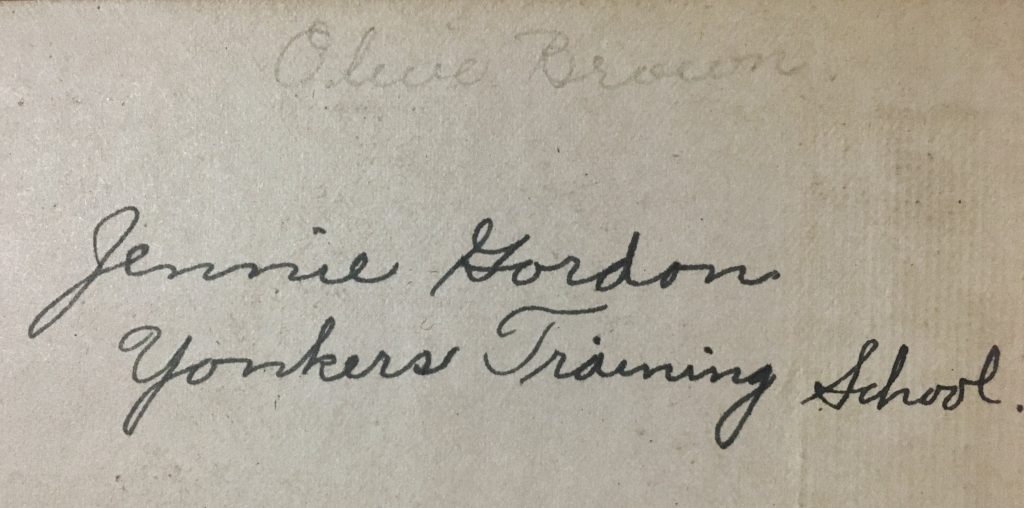

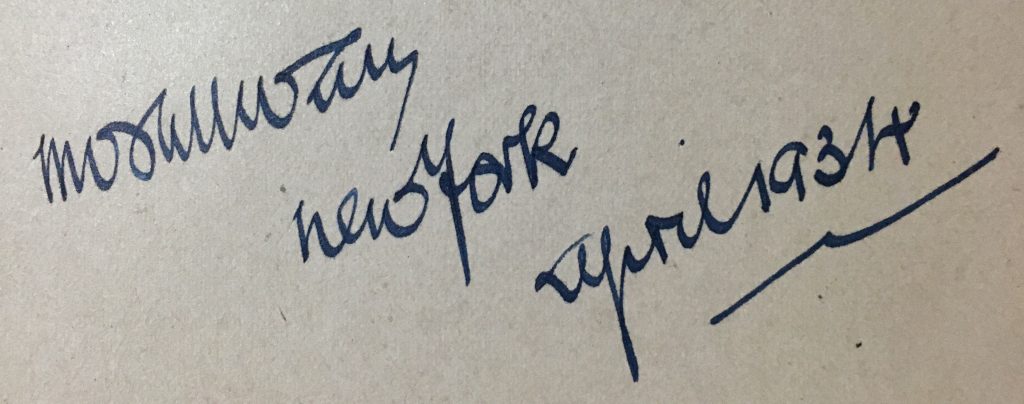

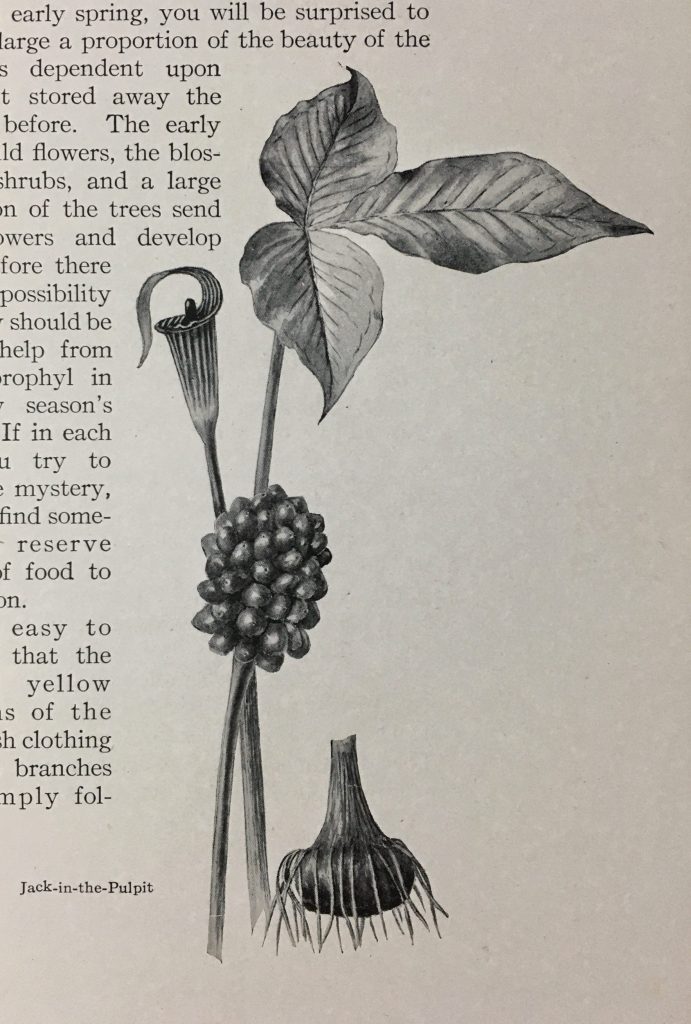

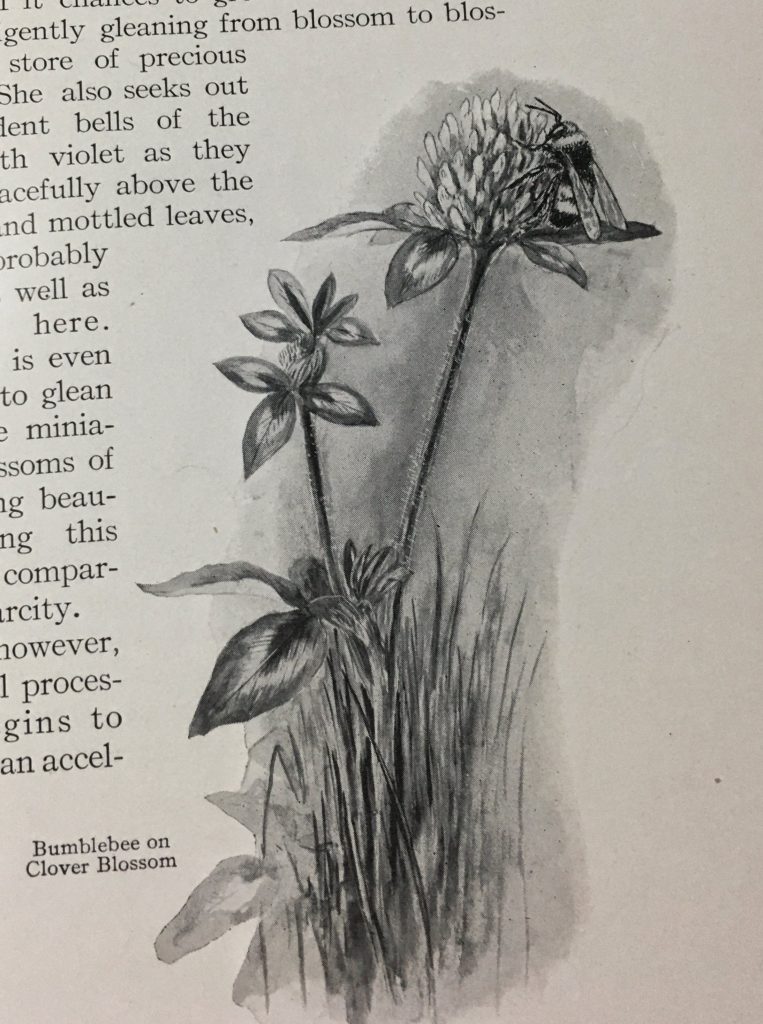

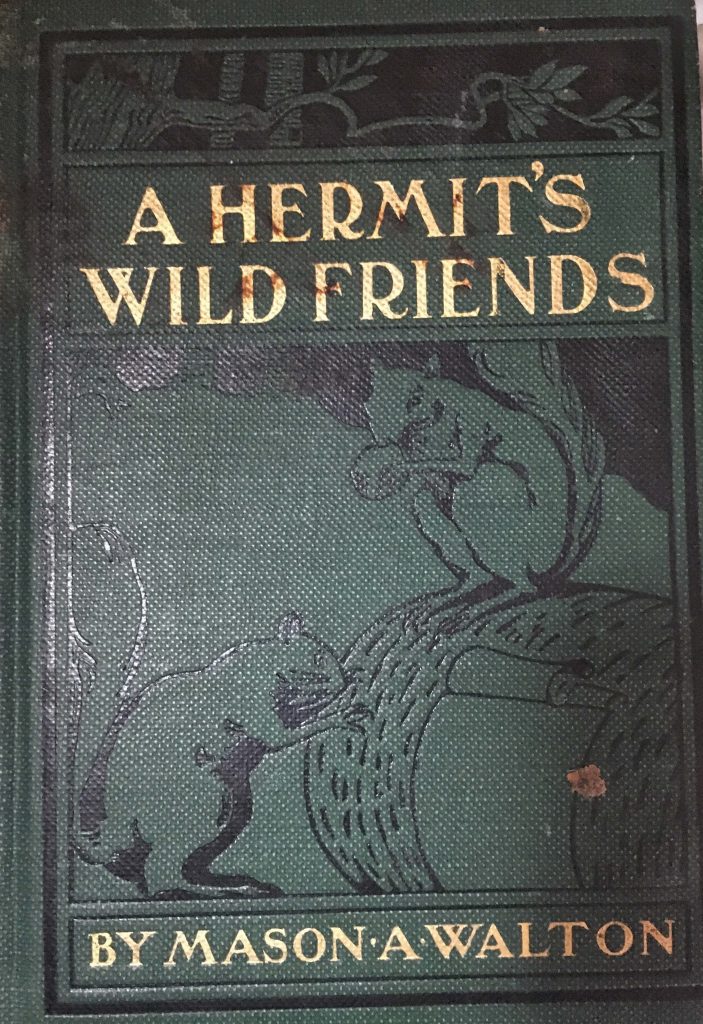

MY VOLUME OF THIS BOOK WAS THE ONLY EDITION EVER PRINTED. A weighty tome, its pages are of heavy stock, interspersed with a variety of images, all black and white. Some are photographs, others drawings by more than one illustrator. The finest of these are full-page images of different birds. The artist of these was none other than Louis Agassiz Fuertes. My copy of the book had one previous owner whose name is written semi-illegibly along the right-hand edge of the inside front cover, along with the date of 4/1913.