In the fifty-two short essays of this volume I have presented familiar objects from unusual points of view. Birds-eye glances and insect’s eye glances, at the nature of our woods and fields, will reveal beauties which are wholly invisible from the usual human view-point, five feet or more above the ground.

Who follows the lines must expect to find moods as varying as the seasons; to face storm and night and cold, and all other delights of what wildness still remains to us upon the earth.

WITH THESE WORDS, THE EXPLORER-NATURALIST WILLIAM BEEBE SETS THE READER ON A JOURNEY THROUGH THE FAMILIAR WILDS OF THE NORTHEAST COAST, FROM JANUARY TO DECEMBER. Clearly inspired by John Burroughs, Beebe intended his first book to be another of many volumes published at the time tracing out seasonal changes in New England and environs (in this case, near New York City). His format: a weekly entry about nearby wildlife, especially birds, capped off with a bit of nature poetry as a nod to the temperment of the age. But at this project, Beebe largely failed. Yes, there are a number of brief pieces about looking at the familiar in new ways, such as studying pond life with a microscope or getting down close to the ground to see the winter world of tunneling mice close-up. But there are a number of chapters — his finest writing in the book, in my estimation — that seek out wilder places such as swamps and marshes or, better still, the open ocean. Indeed, the book’s longest chapter, at twenty-four pages, is Secrets of the Ocean. There is wanderlust in these pages — a world adventurer constrained, for a time, to a single place, seeking to make the most of it. In fact, at one point he celebrates the love of home as a source of abiding connection with the birds he so keenly observes:

This love of home, of birthplace, bridges over a thousand physical differences between feathered creatures and ourselves. We forget their expressionless masks of horn, their scaly toes, and looking deep into their clear, bright eyes, we know and feel a kinship, a sympathy of spirit, which binds us all together, and we are glad.

Clearly, though, while he may appreciate a sense of home, what he truly yearns for instead is wilder places, where humans have not ventured. In wetlands he found an approximation that was temporarily satisfying:

To many, a swamp or marsh brings only that very practical thought of whether it can be readily drained. Let us rejoice, however, that many marshes cannot be thus easily wiped out of existence, and hence they remain as isolated bits of primeval wilderness, hedged about by farms and furrows. The water is the life-blood of the marsh, — drain it, and reed and rush, bird and batrachian, perish or disappear. The marsh, to him who enters it in a receptive mood, holds, besides mosquitoes and stagnation, — melody, the mystery of unknown waters, and the sweetness of Nature undisturbed by man,

The ideal marsh is as far as one can go from civilization. The depths of a wood holds its undiscovered secrets; the mysterious call of the veery sends a wildness that even to-day has not ceased to pervade the old wood. There are spots overgrown with fern and carpeted with velvety wet moss; here also the skunk cabbage and cowslip grow rank among the alders. Surely man cannot live near this place — but the tinkle of a cowbell comes faintly on the gentle stirring breeze — and our illusion is dispelled, the charm is broken.

But even to-day, when we push the punt through the reeds from the clear river into the narrow, tortuous channel of the marsh, we have left civilization behind us. The great ranks of the cattails shut out all view of the outside world; the distant sounds of civilization serve only to accentuate the isolation….

The marsh has remained unchanged since the days when the Mohican Indians speared fish there. We are living in a bygone time. A little green heron flies across the water. How wild he is; nothing has tamed him. He also is the same now as always.

The chapter continues, and night settles in. Beebe revels in the wild sounds and presences all around him, until at least compelled to depart:

All sounds have ceased save the booming of the frogs, which but emphasizes the loneliness of it all. A distant whistle of a locomotive dispels the idea that all the world is wilderness. The firefly lams glow along the margin of the rushes. The frogs are now in full chorus, the great bulls beating their tim-toms and the small fry filling in the chinks with shriller cries. How remote the scene and how melancholy the chorus!….

The moon rises over the hills. The mosquitoes have become savage. The marsh has tolerated us as long as it cares to, and we beat our retreat….

A water snake glides across the channel, leaving a silver wake in the moonlight. The frogs plunk into the water as we push past. A night heron rises from the margin of the river and slowly flops away. The bittern booms again as we row down the peaceful river, and we leave the marshland to its ancient and rightful owners.

ULTIMATELY, THOUGH, IT IS TRUE WILDERNESS HE YEARNS FOR. A microscope or a canoe may carry him out of the familiar for a time, until “the charm is broken”, but the open ocean is far wilder, far more remote, and it calls to him:

We are often held spellbound by the majesty of mountains, and indeed a lofty peak forever capped with snow, or pouring forth smoke and ashes, is impressive beyond all terrestrial things. But the ocean yields to nothing in its grandeur, in its age, in its ceaseless movement, and the question remains forever unanswered, “Who shall sound the mysteries of the sea?” Before the most ancient of mountains rose from the heart of the earth, the waves of the sea rolled as now, and though the edges of the continents shrink and expand, bend into bays or stretch out into capes, always through all the ages the sea follows and laps with ripples or booms with breakers unceasingly upon the shore.

The oceans, too, set a boundary for human destructiveness, or so it seemed to Beebe over a hundred years ago, long before the invention of plastic:

The time is not far distant when the bottom of the sea will be the only place where primeval wildness will not have been defiled or destroyed by man. He may sail his ships above, he may peer downward, even dare to descent a few feet in a suit of rubber or a submarine boat, or he may scratch a tiny furrow for a few yards with a dredge: but that is all.

Alas, Beebe failed to predict so much, from commercial trawler fishing operations to single-use plastic grocery bags…. But in 1906, many years and journeys lay still ahead for him, around the world and into the ocean deeps. He would even return, almost half a century later, to another visit with the commonplace, publishing in 1953 “The Unseen Life of New York” As a Naturalist Sees It”. But for the moment, I will close with one last glimpse of the wilds of a marsh — in this case, a cypress swamp somewhere in the coastal plain of the American Southeast:

…in the mysterious depths of our southern swamps we find the strangely picturesque cypresses, which defy the waters about them. One cannot say where trunk ends and root begins, but up from the stagnant slime rise great arched buttresses, so that the tree seems to be supported on giant six- or eight-legged stools between the arches of which the water flows and finds no chance to use its power. Here, in these lonely solitudes, — heron-haunted, snake-infested, — the hanging moss and orchids search out every dead limb and cover it with an unnatural greenness. Here, great lichens grow and a myriad tropical insects bore and tunnel their way from bark to heart of tree and back again,. Here, in the blackness of night, when the air is heavy with hot, swampy odours, and only the occasional squawk of a heron or cry of some animal is heard, a rending, grinding, crashing, breaks suddenly upon the stillness, a distant boom and splash, awakening every creature. Then the silence again closes down and we know that a cypress, perhaps linking a trio of centuries, has yielded up its life.

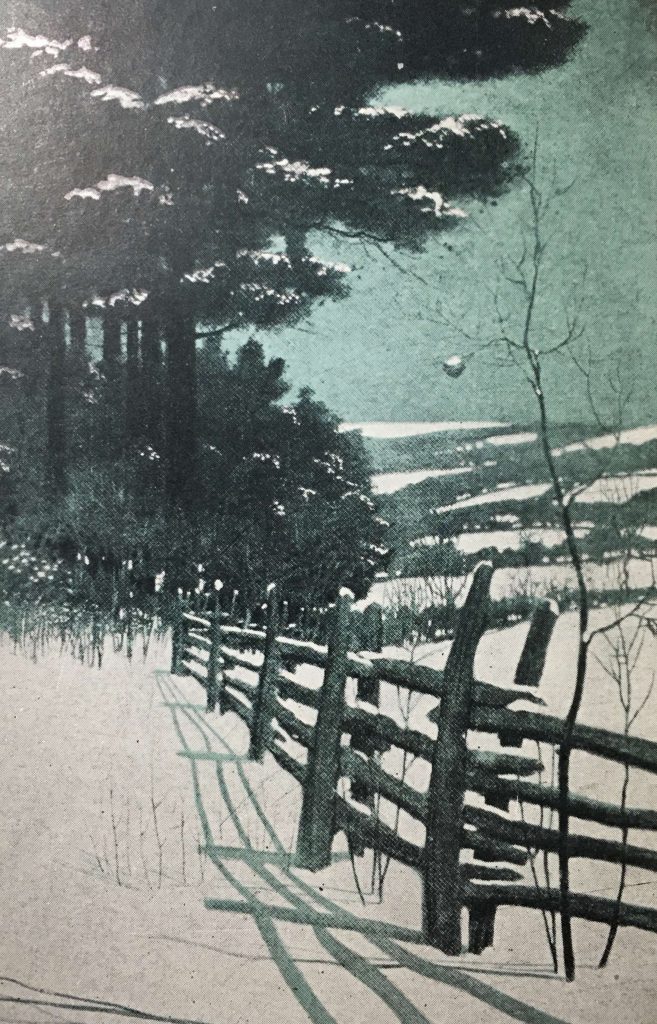

FINALLY, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY BOOK. Not being overly drawn to costlier first editions, I purchased a 1927 copy of Beebe’s work. The book is without a mark, though the pages are considerably browned with age. Alas, apart from the wintertime scene frontispiece shown above (by Walter King Stone), the book is unillustrated.