Every walk about our camp revealed new flowers or seed pods of beautiful colours and strange shapes. We longed for the key to the interrelations of plants and insects, for hints concerning the complicated dependence of all the life about us, — bird on insect, insect on plant, plant on both, which ever links even the extremes of nature.

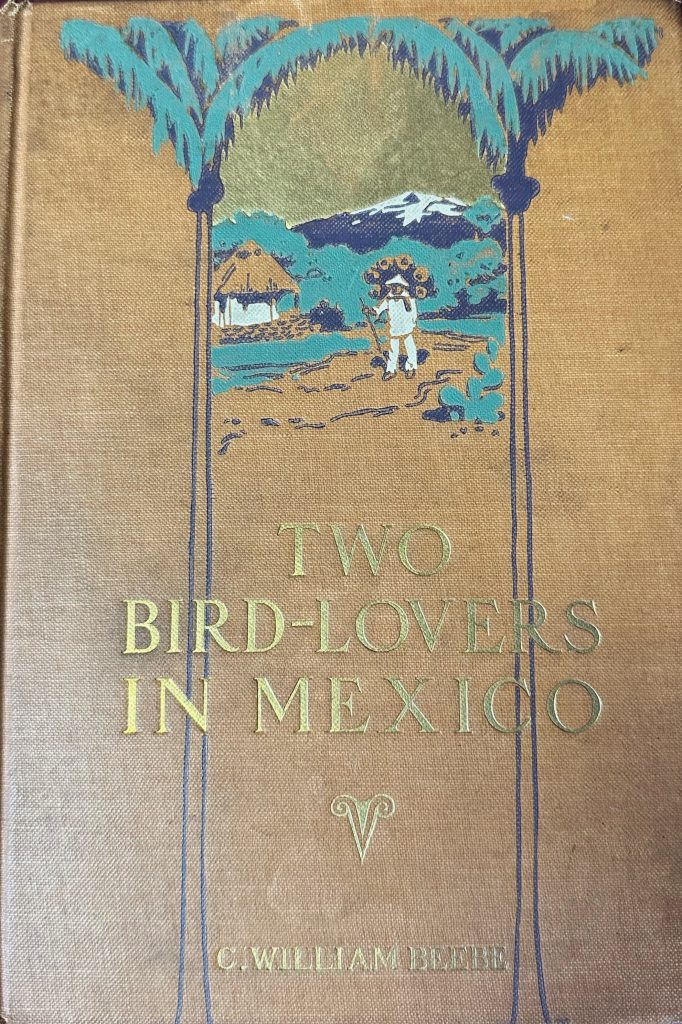

When William Beebe published Two Bird-Lovers in Mexico in 1905, he was 28 years old and nly three-years married to someone as fascinated by nature as he was., Mary Blair Rice. Though they had honeymooned in Nova Scotia after the wedding, their trip to Mexico together from December, 1903 until April of 1904 was a second honeymoon for the two. The stated purpose of the expedition was to study and collect birds for the New York Zoological Park, where Beebe had recently become Curator of Ornithology. Much of Mexico was still wilderness at the time, and the two traveled mostly by horseback through a variety of tropical ecosystems, from desert scrub to lush rainforest, staying in tents at base camps for weeks at a time. Everywhere he went, Beebe was impressed by the rich bird life and the vast number of birds he encountered. For example, on a visit to the marshes surrounding Lake Chapala, he gushed that

…the feelings we experienced cannot be put into words; such one feels at a fist glance through a great telescope, or perhaps when one gazes in wonder upon the distant earth from a balloon. At these tims, one is for an instant outside of his petty personality and a part of, a realizer of, the cosmos. Here on these marshes and waters we saw, not individuals or flocks, but a world of birds! Never before had a realization of the untold solid bulk in numbers of the birds of our continent been impressed so vividly upon us.

There is a youthful vigor to this book. While Beebe would later be famous for his vast number of global expeditions, particularly to the topics, at the time of his trip to Mexico he had never been so far from his home in New York City. He brought with him a zest for seeing wildlife, though his desire to learn all the ways of the local wildlife did not extend to the human cultures of the region, as this whimsical tale of his daily encounters with a local villager makes plain:

Every day about noon, an old, old man drove several forlorn cows down the trail and up past our camp, for a drink and an hour’s feed of fresh green grass. A ragged shirt, a breech-clout, and a pair of dilapidated sandals formed the whole of his outfit. He knew not a word of Spanish, but jabbered cheerfully away to us in some strange Indian tongue, — Aztec, we pleased ourselves by calling it, — as if we understood every word. When he learned that we were afraid to have his half-wild cattle roaming at will about our provision tent, he took great pains, by means of liandfuls of gravel and a torrent of “Aztec” expletives, to banish them to the opposite side of the stream. His greeting was always ”Ping-pong racket!” This may seem absurdly trivial and irrelevant, yet these syllables exactly represent his utterance. “Ping-pong racket!” I shouted to liim as he appeared with his wild charges. “Ping-pong racket!” he answered joyfully, and patted me on the back with an outburst of incoherent gutturals, doubtless expressing his pleasure at my ready grasp of his mother tongue!

He showed us where the purest and coldest spring was to be found, for which we were extremelv grateful. A bowl of frijoles drew expressions of extravagant delight from him. But he seemed most pleased if only we would talk to him, although the words could convey not a particle of meaning. I would converse for a while in my choicest German, then harangue him with all the Latin I could recall and perhaps end witli an AEsop’s Fable, or part of tlie multiplication table. Whether I gravely informed him that Artemia salina could be converted into Artemia muhlenhausii by adding fresh water and stirring, or whether I chanted the troubles of AEneas, the venerable “Aztec” courteously listened with the greatest interest!

His final greeting was tremulous and sincere, and, as we repeated the phrase which sounded so ridiculous to our ears, we felt a strong pity for this poor ignorant man, whose speech was that of long-gone centuries. And yet he had no need of our sympathy. Day after day for years (so we gathered from his sign language) he had driven his cattle back and forth from some tiny village miles away. He was faithful in this and his happiness was full. It was overflowing when, at parting, we gave him some little trinkets and our spare change.

I found this charming and whimsical tale (albeit a bit disdainful on the part of a white American scientist) to be a highlight of the book. Beyond it, the prose was pleasant enough, though lackluster. Beebe was still developing as a writer, and the fact that the book reflected a first journey into uncharted territory meant that he came way from the trip with far more questions than answers. Still, while so much of the narrative was consumed with descriptions of the birds he saw, Beebe also offered glimpses of a more inclusive vision of nature, one that would emerge into the mainstream as the discipline of ecology over the coming decades. While 19th Century writers like Badford Torrey would go for woodland rambls seeking to identify and observe birds and plants just like Beebe in Mexico, Beebe was consumed by the questions of how they related to each other, and how they fit together into a larger whole — a “complicated dependence of all the life”.