It is one of the enjoyable features of bird study, as in truth it is of life in general, that so many of its pleasantest experiences have not to be sought after, but befall us on the way; like rare and beautiful flowers, which are never more welcome than when they smile upon us unexpectedly from the roadside.

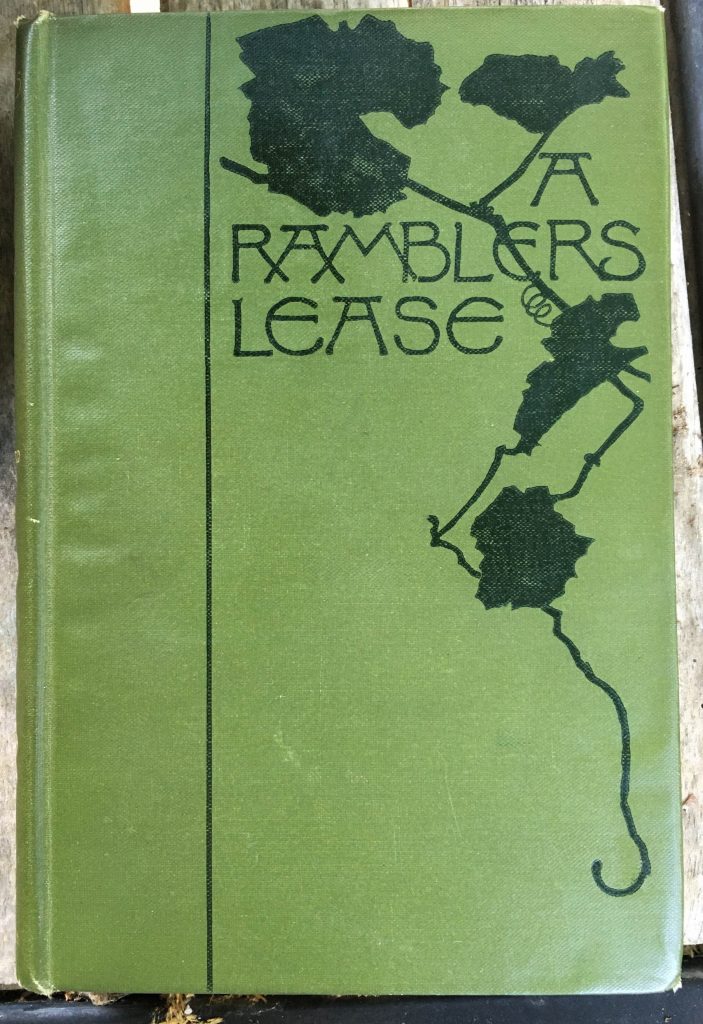

JUST FOUR YEARS AFTER MARY TREAT PUBLISHED HER “HOME STUDIES IN NATURE”, BRADFORD TORREY PUBLISHED THE SECOND OF WHAT WOULD BE TWELVE BOOKS ABOUT NATURE. I suspect, however, the two never met, as they inhabited such different worlds. Mary Treat was a scientist, carefully observing birds and spiders in her backyard; Bradford Torrey was a saunterer, heir to Thoreau, rambling the countryside near his home with a fond familiarity. Known as an ornithologist, he published no scientific studies, but instead did much to encourage city-dwellers and the ever-increasing suburbanites of his native New England to get out into nature and appreciate its wonders. Born in 1843 in Weymouth, Massachusetts, Torrey published his first natural history book, “Birds in the Bush”, in 1885. “A Rambler’s Lease”, a collection of essays he had written for periodicals, followed four years later. Torrey continued writing for the rest of his life, though his productivity declined after 1900, when he took on the task of editing Thoreau’s Journals. (The edition he ultimately published, reprinted by Dover as two immense volumes of 14 books condensed to two, was the one that I read in my own childhood.) In Torrey’s last several books, he reported on travels to various parts of the country: Florida, Tennessee, the Blue Ridge, New Hampshire, and California. Torrey died in Santa Barbara, California in 1912.

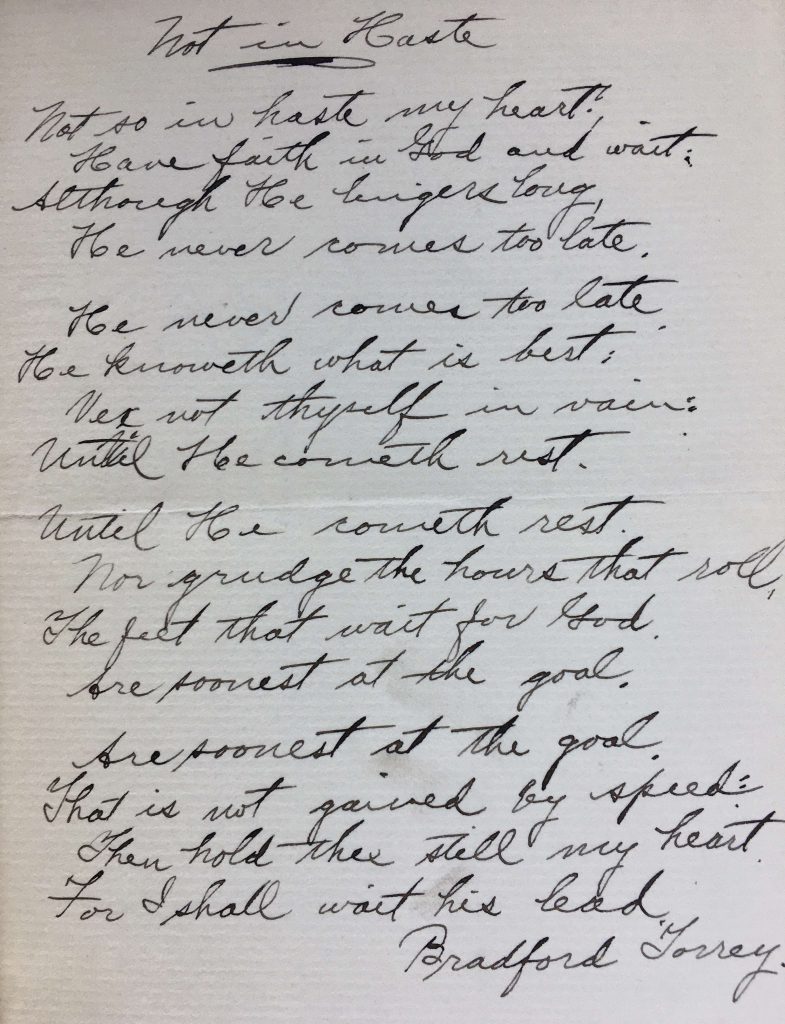

I first met Torrey through another book on my shelf, an anthology of six well-known American nature writers published by Houghton-Mifflin in 1909. The fact that I had never heard of three of them (the other three were, of course, Thoreau, Muir, and Burroughs) kindled my curiosity, ultimately leading me down that path to this blog. I quickly obtained all of Torrey’s works in online editions, but I still longed to be able to hold a copy in his hand. Here, the degree to which he is forgotten today served me in good stead. For a relative pittance, I was able to purchase a first edition of one of his books, in fairly good condition, with a signed original poem by Torrey tipped into the front.

READING IT, I CAN SEE RIGHT AWAY WHY TORREY IS NOT KNOWN TODAY AS A POET. It is more bland than eloquent and more religious than inspiring. Still, it was never published and is in Torrey’s own hand, accompanied by his signature. Apart from this, the book bears practically no trace of its life these past 135 years; all I have to chronicle its journey is a tiny book trade label affixed inside the front cover: W.B. Clarke Co., Booksellers & Stationers, 26 & 28 Tremont St. & 30 Court Sq., Boston.

TORREY MAKES FOR A CHARMING TRAVEL COMPANION FOR THE ARMCHAIR NATURE EXPLORER. I found his prose quite flowing and the author charming and endearing. The volume includes a number of accounts of his “rambles” across the countryside, interspersed with a few more speculative pieces, such as “Butterfly Psychology” (more about those later). At home in the woods, Torrey engages with the animals he encounters (especially birds) as familiar friends. In one chapter, he describes befriending a pair of brooding orioles, to the point that he is able to hand-feed them plant lice, while they are still on their nest. At the same time, Torrey expresses a humble appreciation of the abundance of nature: “I stood in the path…and looked about,” he write of his visit to a nearby tract of land that he had inherited from a relative. “So much was going on in this bit of earth, itself the very centre of the universe to multitudes of living things.”

IN HIS WORK, TORREY PERCEIVED THAT HUMAN LAND USE CHANGES COULD ACTUALLY HAVE POSITIVE IMPACTS ON SOME NATIVE SPECIES. Decades before the term “ecology” entered the lexicon, Torrey was able to observe that clearing a patch of forest for farming could enhance bird life in the area: “…in such a place [a farmed clearing in the woods] one may see and hear more birds in half an hour than are likely to be met with in the course of a long day’s tramp through the unbroken forest….. Up to a certain point, civilization is a blessing, even to birds. Beyond a certain point, for aught I know, it may be nothing but a curse, even to men.” I will leave the 21st century reader to render a verdict on that.

WHILE TORREY HAD A KEEN EYE FOR NATURAL HISTORY, ESPECIALLY BIRD BEHAVIOR, HE ALSO HAD A POETIC SIDE THAT HE SOMETIMES FELT COMPELLED TO DEFEND. In a passage from his essay on “Esoteric Peripateticism”, he argues for sometimes approaching the landscape as a poet rather than as a naturalist: “…it is a blessing to be able on occasion to leave one’s scientific senses at home….. There are times when we go out-of-doors, not after information, but in quest of a mood. Then we must not be over-observant. Nature is coy; she appreciates the difference between an inquisitor and a lover. The curious have their reward, no doubt, but her best gifts are reserved for suitors of a more sympathetic turn….. One may become so zealous a botanist as almost to cease to be a man. The shifting panorama of the heavens and the earth no longer appeals to him.” With these words, Torrey plants himself firmly on the terra-firma of late 19th century natural history writing — a golden age when scientific scrutiny often alternated with poetic reverie. Sometimes, as in many of Torrey’s essays in this book, the two would flow together. At others, such as in Mary Treat’s essays, the poetic allusions feel somewhat forced or as an afterthought.

AT THE SAME TIME, TORREY CONFESSES ON MORE THAN ONE OCCASION TO ANTHROPOMORPHIZING WILDLIFE. Speaking as an ornithologist, Torrey remarks, “To borrow a theological term, my conception of bird nature is decidedly anthropomorphic, and I incline to believe that chickadees as well as men find it easier to blame others than to do better themselves.” In perhaps the most odd essay in the book, “Butterfly Psychology”, Torrey wonders about how butterflies encounter their world. Do they wonder how they came into being? Do they recognize the brevity of their lives? To what extent are they able to recognize and appreciate beauty? After several pages of such wild speculations, he defends such musings with a bit of self-deprecation: “It is my private heresy, perhaps, this strong anthropomorphic turn of mind, which impels me to assume the presence of a soul in all animals, even in these airy nothings; and, having assumed its existence, to speculate as to what goes on within it.”

AT THIS POINT, I CANNOT RESIST COMPARING BRADFORD TORREY’S APPROACH TO NATURE WITH THAT OF MARY TREAT, THE CONTEMPORANEOUS SCIENTIST. Both studied bird behavior, including making close observations of nesting birds. Both had some interest in botany, though Torrey was more at home listing common names, which Treat kept to resolutely to scientific ones. It is in looking at their approaches to insects that the clearest difference emerges. Mary Treat approached ants and spiders and wasps with fascination and patient observation, seeking to know their minds (which she argued they had at a time when many people thought otherwise) by studying them meticulously. Torrey, on the other hand, approached butterflies with imaginative inquiry, wondering about they extent to which their own thoughts and feelings mirror those of human beings. His poetic musings entertain the reader, but do not really add to our scientific understanding of how nature works.

BOTH TREAT AND TORREY HAVE ENCOURAGED ME TO SPEND MORE TIME OBSERVING NATURE, A TREND THAT I HOPE WILL CONTINUE THROUGHOUT THIS JOURNEY. I envy Torrey his countryside rambles, and would love to take more of my own. In the case of Treat, on a recent dog walk I paused to inspect some spider burrows topped with turrets, wondering if the spiders who constructed them could belong to the same genus as the ones that Treat studied. Here are a couple of photographs that I took yesterday of these fascinating constructions: