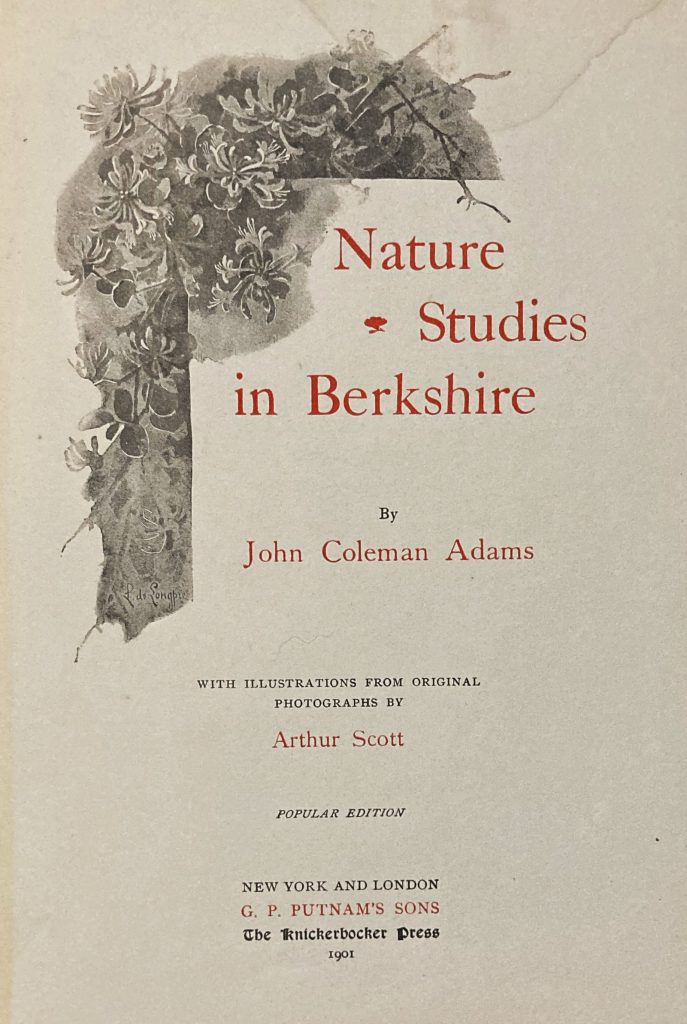

John Coleman Adams (1849-1922) graduated from Harvard Divinity School in 1872 and went on to serve as pastor at five Universalist churches during his lifetime. He wrote several books on religion, philosophy, and other topics. Nature Studies in Berkshire was his only book in the nature genre unless one counts a biography of William Hamilton Gibson, another nature author of the time.

At first glance, I was fearful that the book was going to be, well, vacuous. The opening chapter on “Our Berkshire” is a work overwrought with boosterism that includes this cliché-riddled passage:

To know Berkshire is to love it. To love it is to feel a sort of proprietorship in it, a pride in its glories, a joy in its beauties, such as owners have in their estates, and patriots in their native land. He who was born here, clings to the soil if he stays, or reverts to it if he moves from it, with a New England stead- fastness, as intense and deep as a moral principle. He who visits Berkshire is almost certain to visit again and yet once more. He would fain revel in the old delight of air and scene and influence. He believes he has not exhausted the possible experiencesto be found in this spot. And so the charm grows, and the sense of belonging to the soil, and the belief that there is nowhere the like of this blend of tonic and restful scenery, of wild nature and cultivated land, of hill-country and broad plains.

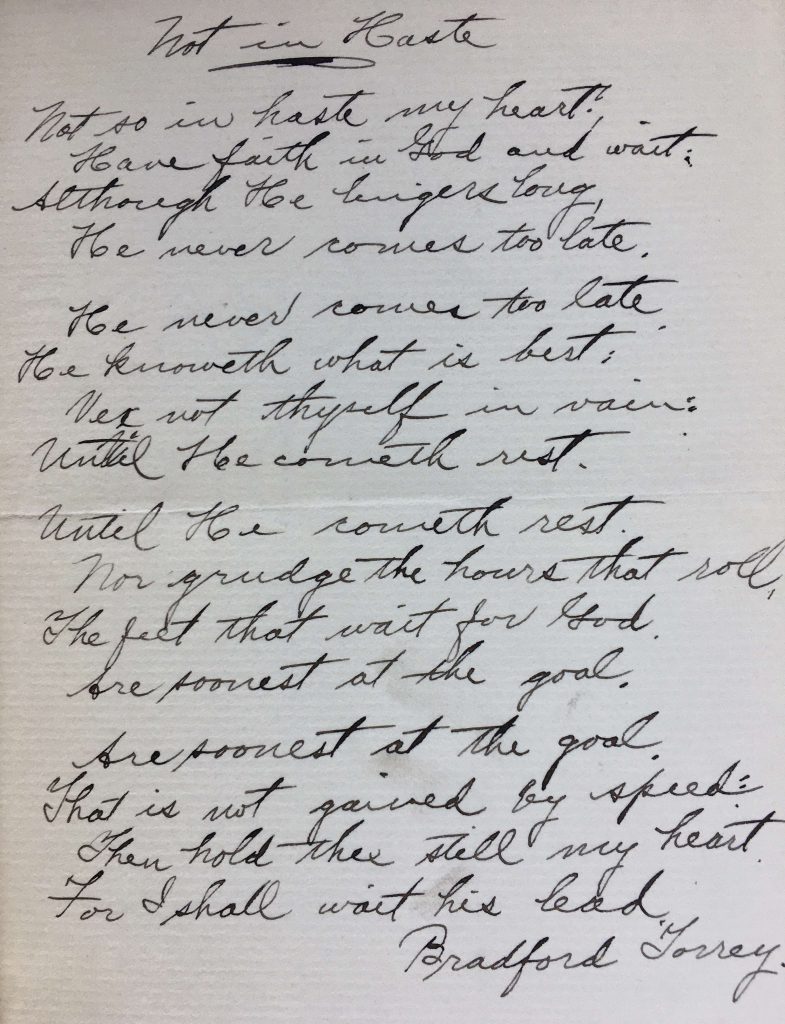

I am grateful to report that the book gets much better. As a dominie (the term for a pastor that Adams preferred to apply to himself), he includes some religious sentiment; but it is muted for the most part, and not overly didactic. I found it strangely endearing to read, early on, Adams’ declaration that “I am a stranger in bird-land”; so many other writers of the time, such as Olive Thorne Miller and Brandford Torrey, reveled in descriptions of the feathered folk. Birds still appear here — robins, thrushes, and a few others — but only briefly, and mostly concerning their songs or behaviors, not their plumage or nesting habits. His botanical knowledge is much stronger; unlike early Burroughs, Adams identifies the wake-robin trillium as being deep purple. In his 1901 biography of William Hamilton Gibson, Adams identifies Thoreau, Burroughs, and Gibson as the greatest nature writers of the time. In this slightly earlier book, Adams mentions John Burroughs, Grant Allen (stay tuned for a future blog post or two on this Canadian writer who wrote popular pieces about plant evolution), and Bradford Torrey, along with the poetry of Wordsworth and Emerson.

I found the simple, straightforward nature of Adams’ prose to be quite refreshing after Field-Farings. I lifted the title of this blog post from the book because I think it describes Adams’ audience well — novices at nature study, those seeking inspiration in charming accounts of the out-of-doors. Nearly all of the chapters are set in the summer because that is when Adams would stay in the Berkshires; the rest of the year, he was a parson at All Souls’ Universalist Church in Brooklyn. The chapters are accounts of excursions he took in the area, or reflections upon various landscape features — trees, brooks, lakes, and clouds. While his prose rarely waxes eloquent, I admit to enjoying this passage about a delightful afternoon visit to a stream near his home:

…sweetest of all our memories will be that bright morning when we wandered to the brookside, with a little child for company, and lay stretched on a greensward shaded by the meeting boughs of a maple and a butternut, while she played like a baby naiad in the stream, and the brook sang, and the trees whispered, and the birds hopped on branches close beside us, and the kingfisher from downstream dropped in to call, and the tenant frog stared at us from his pool, and the oxen in the next lot sent looks of fellowship across the stone wall, and we seemed to blend our lives with that of the brook, and for each of us, child, man, and woman, the poet’s word was true: ” Beauty through my senses stole; I yielded myself to the perfect whole.”

Like many nature authors of his time (particularly of the religious persuasion), Adams believed that connecting with nature was ultimately a religious experience. He explained the connection between religion and nature thus:

I have grown to feel that the love of nature and its beauty and inner life have much to do with the enrichment of the religious life. Religion has been the gainer both from science and art, for these interpreters of nature have broadened our vision, lifted our ideals, and expanded all our conceptions of the universe and of its Creator.

I am confident that Hamilton Wright Mabie, among others, would have agreed with him.

Before I consign this book to my rapidly expanding “finished books” shelf, I will share excerpts from three chapters in the volume that particularly caught my attention. The first is a passage singing the praises of the music of the thrush in the forest:

The breeze lulls for a moment ; the far sounds from the farms come to our ears softened and sweet. But best and dearest of all sounds, across the glen, from out those woody coverts, there floats the tender, liquid trill of the thrush. It is the harbinger of the evening, the first notice the birds serve that the day is waning, and that the shadows are gathering in the forests on the eastern slopes. There is no other woodland note like this. It is perpetual music. It touches the emotions like profoundest poetry. It calls on the religious nature and stirs the deepest soul to joyous praise. There is no bird, among the many which have found their way into song, in other lands or other times, whose note deserves so much of poet and lover of nature as the wood-thrush. The very spirit of the forest thrills in this vesper-song. It is the trembling note of solitude, rich with the emotions born of silence and of shadow, rising like the sighing of the evergreens, to fill the soul at once with joy over its sweetness, and with sadness because that sweetness must be so evanescent. When one has heard the song of the thrush there is no richer draught of joy in store for him in any sound of the woods. There is nothing to surpass it, save the ineffable ecstasy of the silence which reigns in their deepest shades.

The second excerpt presages Edwin Way Teale’s North With the Spring, published half a century later:

Now if I had the means and the time, I should every year in this same fashion run ahead of the vernal advance, the procession of leaves and blossoms and birds and butterflies, as it moves northward from the Carolinas to the Canadas. There is such an exquisite pleasure in watching the burst of life, the outbreak of colour and fragrance, the clothing of field and forest with verdure, that one would be glad to prolong the sensation. In these days it would be an easy matter to keep just ahead of summer for a good two months. And then one might halt on the banks of the St. Lawrence and let the pageant pass by; for when it has gone as far north as that, the line of march is nearly done.

Finally, I was surprised to find in Adams a kindred spirit with Enos Mills. Indeed, one might imagine the two meeting for conversation — the New England parson extolling the rural delights of the Berkshires with their “gracious air of culture and refinement”, and a John Muir wannabe backwoodsman with endless tales to tell of adventures in the rugged Rockies. Both men, however, clearly recognized the importance of trees to civilization and the environment. Indeed, many points Mills offers about the value of forests to humans and ecosystems in “The Wealth of the Woods” from The Spell of the Rockies (1911) also appear in Adams’ 1899 essay, “Fruitful Trees”. I suspect that both writers were in turn influenced, at least in part, by George Perkins Marsh’s much earlier work, Man and Nature (1864). “Nature has made the tree one of the great conservators of the soil,” Adams declares. He goes on to explore how trees moderate the local hydrology (diminishing the severity of floods and droughts) and play a key role in preventing soil erosion.

…cut down the trees, clear the hillsides, and see what happens. The thin soil, no longer protected by the trees, no longer held in place by their netted roots, no longer shaded by their leafy branches, grows dry, and crumbles, and loosens. The heavy rains wash it bodily into the valleys. The bare ledges appear. The vegetation dwindles. The hill or mountain becomes a barren crag. Its brooks and springs dry up as soon as they are filled. The drench of the hillsides is hurried in bulk down into the valleys; and every rain-storm becomes a swift freshet, destroying the crops and threatening house, barn, and factory, at the same time that it washes down the sand and gravel from the heights to deaden and impoverish the lowland meadows. But as soon as the rain stops, the streams stop too. They dry up and shrink in their beds. They disappear under the scorch of the sun. The same fields which were inundated in the springtime are parched and dusty in the heats of midsummer. That is the way we are enriching ourselves. We are paying dividends at the sawmill, and putting mortgages on the farms. We are burying our fields at the same time that we are destroying our forests.

On the whole, I found Adams a worthy nature writer. And any lightness in his prose was more than counteracted by the weight of his book: 2.4 pounds, with pages made of some of the heaviest paper I have seen — approaching cardstock. The photographs are lovely, each one shielded by vellum with a brief text excerpt printed in red ink. It was a charming read. Alas, no previous owner left their mark, so I cannot tell anything about the history of this volume itself, beyond the fact that it was a slightly later edition of the work, published in 1901.