I knew the desert at first hand, and wrote about it with intimate knowledge… That was a summer of strange wanderings. The memory of them comes back to me now mingled with half-obliterated impressions of white light, lilac air, heliotrope mountains, blue sky. I cannot well remember the exact route of the Odyssey, for I kept no record of my movements. I was not traveling by map.

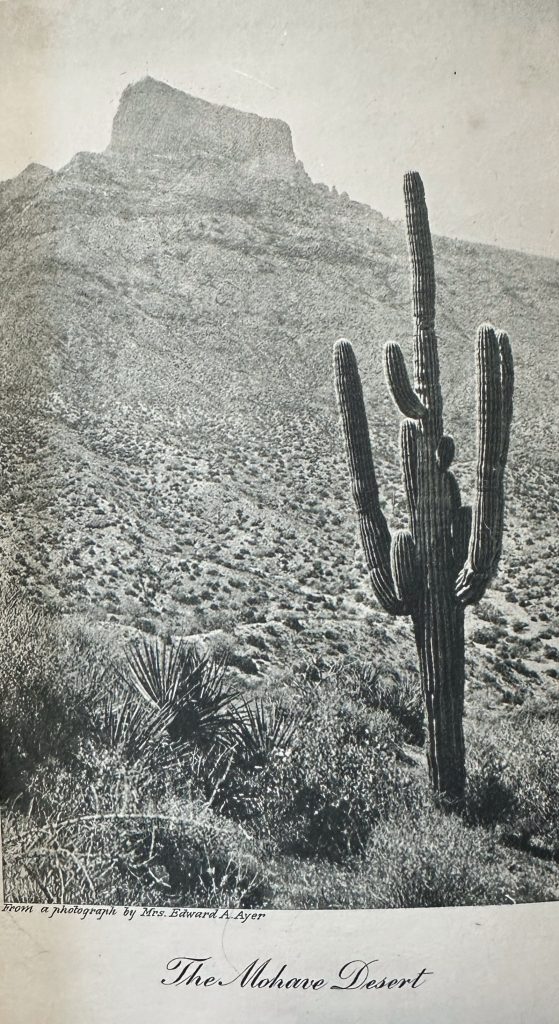

There is something suspect here, when I contrast these words, from John C. Van Dyke’s book The Open Spaces, with the photograph that adorns the frontispiece (in fact, the only image in the book). The Mojave (as the desert is now spelled) extends nearly 48,000 square miles, sprawling from California and Nevada down into Mexico. Van Dyke could have selected any image that would capture its immensity, the vastness of its sky, and the stark majesty of its landscapes. Instead, we have a photograph of a saguaro cactus against a backdrop of yuccas and a distant mesa. Unfortunately, saguaros do not grow in the Mojave Desert. They are restricted to the warmer, wetter climate of the adjacent Sonoran Desert. In his masterpiece, The Desert (stay tuned for a review), Van Dyke reports on wandering both deserts. Only his descriptions of the Sonoran Desert include multiple obvious observational errors. For instance, the saguaro blossom is white, not purple. That is because he most likely never visited the Sonoran Desert.

This post is, of course, not a review of The Desert, but rather, The Open Spaces: Incidents of Nights and Days Under the Blue Sky. Nonetheless, this book is considerably overshadowed by the former work. Abundant research (particularly the work of the late Professor Peter Wild of the University of Arizona) now shows that Van Dyke did not wander about through the desert on his own as he claims here. Instead, he sat on the porch of his brother’s Mojave Desert ranch and wrote most of the book from there. He was an East Coast aesthete, a friend to rich financiers like Andrew Carnegie, and fond of a posh upper-class lifestyle. An art historian who taught at Rutgers, Van Dyke conducted early research on Rembrandt, then explored the beauty of natural settings — including the desert — over a series of six books. The final volume of the six, The Meadows, was previously reviewed in this blog. The other five await their turn on my bookshelf. What I find challenging — a difficulty quite germane to the present volume and review task — is that I simply cannot trust Van Dyke. Am I to read his reminiscences as fiction, rather like The Education of Little Tree? Can I believe him if the same account appears in his autobiography (also on my TBR list)? I know he traveled extensively — to the West Indies and the East Indies, both documented in other books of his. But am I to believe he canoed the Mississippi as a child or ranched in the wilds of eastern Montana as a young man? What am I to make of his memories? How embellished are they?

It is certainly true that, at his best, John C. Van Dyke was a superb craftsman with language. The Desert, despite its flaws and sketchy origins, is still published today. Heck, no less than Ed Abbey referred to it as one of the most important books to read about the desert Southwest. It singlehandedly shifted American views about deserts from avoidance to desire. The vast populations of Tucson, Phoenix, and Las Vegas are testimony to what he accomplished. It is the progenitor to a thousand volumes of nature essays exploring and celebrating the American desert regions. Now, that said, it is tempting to refer to Van Dyke as a “one-hit wonder”, like the singer Don McLean, whose “American Pie” catapulted him to stardom (OK, “Vincent” is a lovely song, too — and is even about an artist — I would like to think Van Dyke would have enjoyed it also.) Peter Wild worked to get other Van Dyke books back into print in affordable paperback editions, including the other five nature volumes and The Open Spaces. (Since his death, all but The Desert are out of print again.)

But The Open Spaces is certainly not the equal of The Desert. Ironically, my favorite passages in the book are probably the few reflecting on his time in (or near, at least) the desert. The rest rambles through memories of camping outdoors as a rancher in Montana, boating the Mississippi as a child growing up in Minnesota, and hunting and fishing in various places. Two threads run through the work, loosely tying it together. First, there is a nostalgia for what has been lost. By 1922, many birds and large mammals had been radically reduced in number. The American buffalo could be written off as a goner. The passenger pigeon was extinct, though Van Dyke recalled how its numbers once darkened the skies:

…in 1870, or perhaps it was 1872, the sky was darkened with flocks of wild passenger-pigeons. Again and again, day after day, I saw passing up the Mississippi Valley cloud-flocks of pigeons that extended from the Wisconsin to the Minnesota bluffs, a distance of five miles. The flocks continued daily and all day long for several weeks. Everybody shot into the nearer and smaller flocks, until the pigeon became a nuisance in the kitchen and an unappetizing article of food on the table. In that year the passenger pigeons had a monster roost in the Mississippi bottoms near the mouth of the Chippewa River, where the birds swarmed like bees, where every litde tree was loaded down with nests, and eggs, crowded out of the nests, were lying on the ground so thick that one could hardly step without crushing them. When the young pigeons were half-grown and could not yet fly, some “sportsmen” went there with clubs, shook and beat the trees until the young birds fluttered out and fell to the ground, and then the “sportsmen” tore their breasts off with their forefingers, flung the breasts into a bag, and threw the carcasses on the ground. That is the wretched kind of thing that one does not like to write about or think about, and yet it was perhaps just such butchery that was responsible for the absolute extinction of this bird. There were such numbers of them then that scarcity seemed a word to laugh at. The roar of that pigeon-roost — a roar like a distant waterfall — could be heard at Wabasha eight miles away. The roar came from the “knac-a” call of the birds, mingled with the flutter and beat of countless wings.

Elsewhere, John C. Van Dyke reflects on how “automobilists” have contributed to despoiling the West — in this case, the stunning mountain meadows of the California Sierras:

Unfortunately, these wonderful places are now being desecrated, if not destroyed, by the automobilist — the same genius that has invaded the Yosemite and made that beautiful spot almost a byword and a cursing. No landscape can stand up against the tramp automobile that dispenses old newspapers, empty cans and bottles, with fire and destruction, in its wake. The crew of that craft burn the timber and grasses, muddy up the streams and kill the trout, tear up the flowers, and paint their names on the face-walls of the mountains. They are worse than the plagues of Egypt because their destruction is mere wantonness.

John Burroughs, the Sage of Slabsides himself, loved his Model T, a gift from his friend Henry Ford. And I am sure Van Dyke traveled considerably by automobile in his later years. Such are the contradictions of many a nature writer — stretching way back to Thoreau, walking home from Walden Pond on the weekend to dine with his parents.

A second thread, less pronounced but more intriguing, is a celebration of wild open spaces. Given Van Dyke’s preference for comfort, there is abundant irony here. But I do think there is still a note of sincerity to his musings in the opening chapter:

What a strange feeling, sleeping under the wide sky, that you belong only to the universe. You are back to your habitat, to your original environment, to your native heritage. With that feeling you snuggle down in your blankets content to let ambitions slip and the glory of the world pass you by. The honk of the wild goose, calling from the upper space, has for you more understanding, and the stars of the sky depth more lure. At last, you are free. You are at home in the infinite, and your possessions, your government, and your people dwindle away into needle points of insignificance. Danger? Sleep on serenely! Danger lies within the pale of civilization, not in the wilderness.

Similarly, Van Dyke closes off the final chapter with these musings:

Had man always lived in the open and maintained a healthy animalism, he would perhaps have been better advised. He was bom and equipped as an excellent animal, but he sold his birthright for a mess of pottage called culture and took on fear and a whimper as a part of the bargain.

Will he always be able to live up to his bargain, holding himself above and superior to nature? Culture is something that requires teaching anew to each generation. Nature will not perpetuate it by inheritance. On the contrary, animalism is her initial endowment; it has been bom and bred in the bone since the world began. Man cannot escape it if he would. Will not Nature in her own time and way bring man back to the earth?

It is tempting to read these lines as a celebration of living close to nature, and maybe Van Dyke wanted to believe that himself. But they are not matched by his somewhat disparaging treatment of native people throughout the book. More than once, he emphasizes that their minds are constantly occupied with meeting material needs (particularly food) and therefore they lack a more spiritual sensibility. I suspect this was a mindset of the time. And for all he writes about encounters with Indians, I am skeptical as to whether they even happened.

As an aside, I found this book enlightening in helping me make connections between John C. Van Dyke and other Van Dykes, as well as John Muir. From this book, I learned that Henry Van Dyke (encountered elsewhere in this blog) was a cousin, while Theodore Strong (T. S.) Van Dyke, owner of a Mojave Desert ranch and advocate for western settlement and development, was his older brother. (T. S. wrote a few books of his own about Southern California, but the parts on nature tended to emphasize the opportunities for fishing and hunting.) And John C. Van Dyke even met John Muir! Sometime in the last seven years of Muir’s life, he showed up at the ranch of T. S. Van Dyke, accompanied by his ailing daughter who was seeking a better climate to aid recovery. Unlike Enos Mills (who encountered Muir on a California beach), Van Dyke was less overwhelmed by the encounter. He tells the tale this way in The Open Spaces:

For several days on the Silver Valley Ranch in the Mohave Desert, with John Muir, I kept bothering him with questions about flower and weed and shrub. What was the name of this or the variety of that ? Learned botanist that he was, his usual answer was: “I don’t know.” The desert growths puzzled him and some of them were wholly incomprehensible to him. He was not afraid to say, “I don’t know,” because there were so many things he did know. When Muir gave it up, no one else ventured a further guess.

The prospect that all was not warm between the two is further hinted at in Van Dyke’s autobiography, in which he remarks that “He liked my book on the desert, he liked my brother who lived in the desert, and he thought he might like me. Well, at any rate, I liked him.” Indeed, Dix Van Dyke (son of T.S.) described in print in 1953 (according to an essay by Peter Wild) how the two “wrangled incessantly” and that sometimes Muir would even stomp off in outrage.

A few words about my copy of this book. It has a nondescript army-green cloth cover. The title is in gold at the top, and below that is an image evoking a Western landscape. The book has a history as a loaner. At one point, it was book 814 of the Indiana Traveling Library. I am guessing that it eventually settled down in Vevay, Indiana, as a guest of the Switzerland County Library. From 1919 until 1992, the library was in the building above, which is now Town Hall. In a delightful twist of fate, the building above was constructed with funds from the Carnegie Corporation, and was the last Carnegie library constructed in Indiana. Andrew Carnegie, a close friend of John C. Van Dyke, would have been delighted to know that his library held some of John C. Van Dyke’s books. It is entirely possible that the book was discarded around 1992, when the library shifted to its current building across the street.