Nothing in nature is isolated. Everything is somehow connected with everything else. There is interaction everywhere between climate and plant life, between plants and insects, between insects and higher animals, and in that way the chain of life runs on and on. The organic is linked to the inorganic; the whole universe is one.

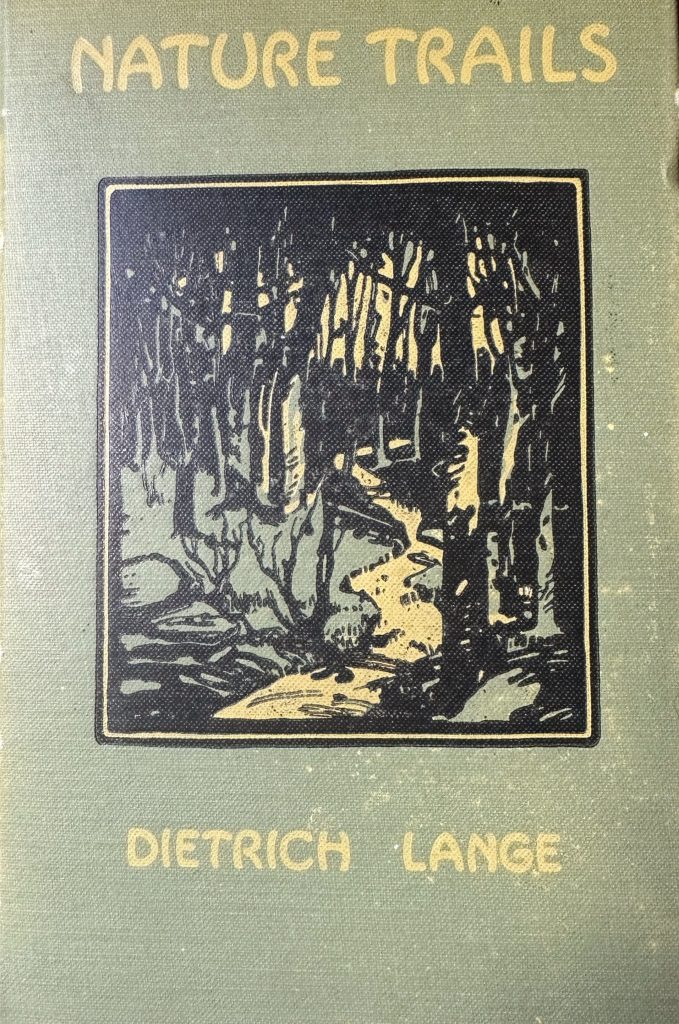

This passage opens a brief essay on the distribution of trees in North America in Lange’s work. It captures that nascent ecological vision that quite a few early 20th-century naturalists observed and pondered. It also stands out in a work that, while well-crafted, is directed toward an audience of older children, to encourage them to get outdoors and appreciate its wonders. Indeed, Lange served at various times in his life as a supervisor and a director of nature study programming in Minnesota. At the time his book was published, he was serving as principal of the Mechanic Arts High School in St. Paul.

I was excited to discover this title a few months ago, because for the considerable sweep of time this blog covers (almost 100 years, from 1850 to WW2), so many parts of the country remain unrepresented by nature writers. I have found dozens in Massachusetts, for example, but very few in Connecticut. Up until this book, I had not found any from the Upper Midwest. Lange, himself, was not a native. He was born in Bonstorf, Germany on June 2nd, 1863, traveling with his family to Minnesota at age 18. He held various teaching and principal positions in and around St. Paul throughout his adult years. He wrote at least fifteen works of both fiction (often featuring boy scouts) and non-fiction (nature-themed, particularly birds). He also published a handbook of nature study for teachers and pupils in the elementary grades. He died in St. Paul in 1940 of unknown causes.

As a nature writer, Longe was eager to encourage young people to “observe, investigate, and enjoy” nature. He listed among his own inspirations the works of Thoreau, Burroughs, Muir, Dallas Lore Sharp, and Gilbert White. Elsewhere, he quoted Bradford Torrey, mentioned C.C. Abbott, and recommended Ernest Ingersoll’s book, “Nature’s Calendar” (blog review coming soon). On the whole, he spoke up for environmental conservation at a time when relatively few animals (apart from birds) were given any protection. He called for game laws to protect bears, for instance, and also protections for orchids (which were being driven extinct by enthusiastic collectors and bouquet gatherers). “It was, perhaps, natural that in the pioneer stage of our country everybody should have been allowed to cut, pick, and burn; to kill, trap, and catch as he pleased,” Lange wrote. “We have now conquered the continent, and the days of the pioneer are gone, but we are still altogether too much a nation of destroyers and exploiters of all that is useful and beautiful in our land.” But lest we exalt Lange too highly, this nature writer who found a place in his heart (and in natural ecosystems) for giant ragweed also argued that the extinction of venomous snakes was “desirable”.

In keeping with Lange’s calling as a nature study teacher, the book includes an appendix on outdoor nature study, with questions to encourage students to engage with the natural world around them.

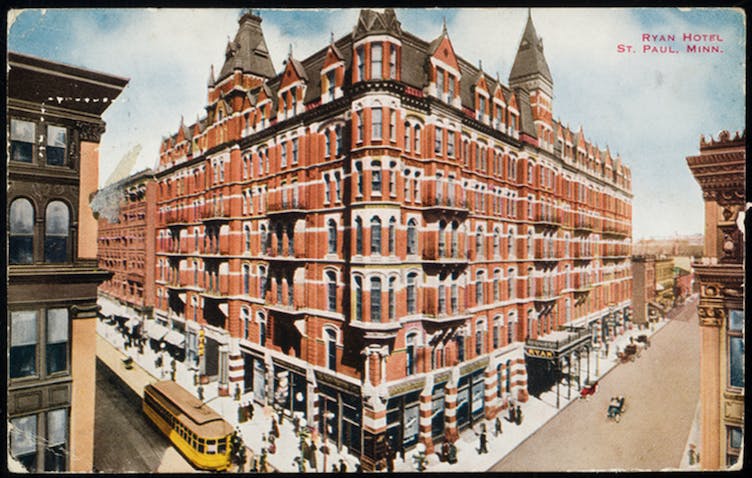

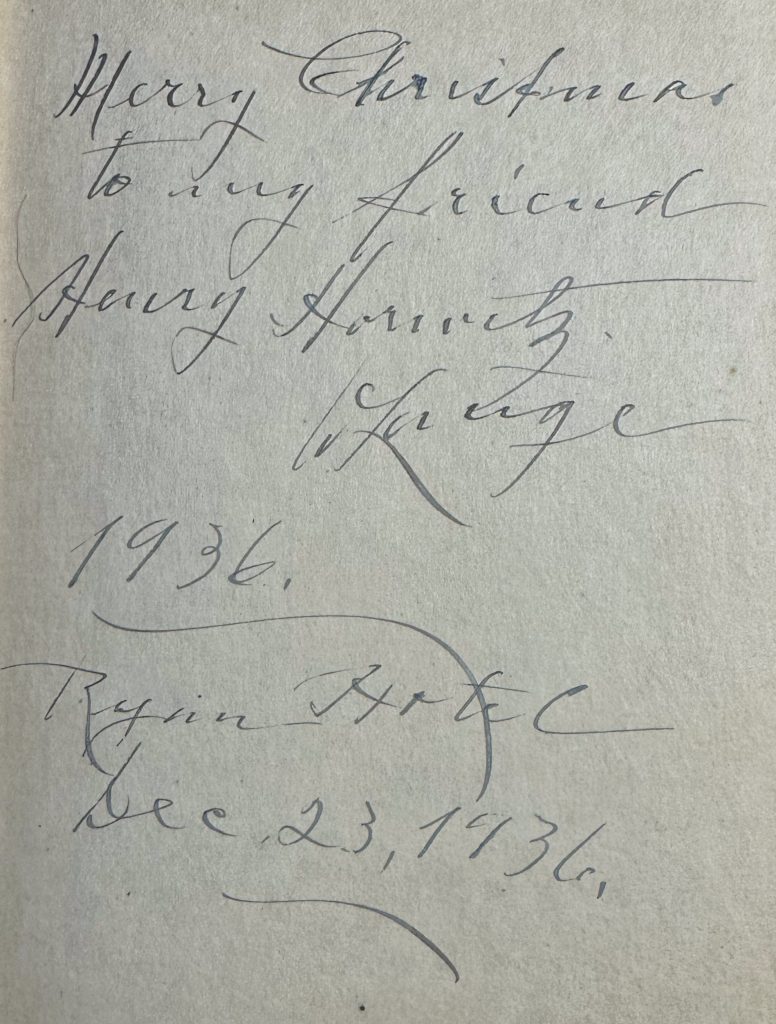

My copy of this book has considerable text on the flyleaf. As well as I can discern the writing, it reads “Merry Christmas to my friend Henry Horowitz. D. Lange. 1936. Ryan Hotel, December 23, 1936.” I pursued this puzzle a bit further, locating a circa 1900 postcard of the opulent Ryan Hotel in St. Paul, which stood downtown from 1885 until it was demolished in 1962 (see below). I even found a potential recipient of the dedication. Henry Alchanon Horowitz (1906-1990) was living at the time in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. It could be him, though I would have felt more confident to have located someone living in Minnesota at the time.