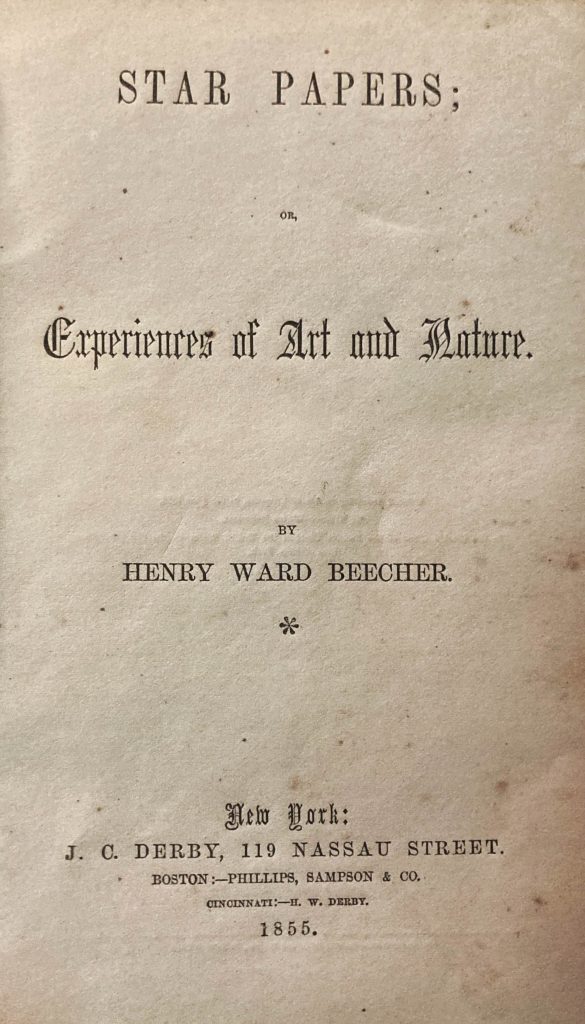

I am not quite certain what to make of this book or its author, Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887). A contemporary of Thoreau, the two may have met but were certainly not close acquaintances. Thoreau does report in his journal about attending church in New York City to see him preach. It is not known whether Beecher, a Unitarian clergyman, ever read Emerson or Thoreau. Beecher wrote one novel — Norwood — entirely unknown today, though his sister’s novel remains famous for helping start the Civil War (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin). Beecher published only this one collection of writings that included nature essays (among other topics in the volume). Yet he is not an obvious progenitor of any later nature authors, although he did develop a close friendship with William Hamilton Gibson late in his life (this friendship included marrying Gibson and Emma Ludlow Blanchard in 1878). The book title is one of its most mysterious features, though there is no cosmic significance intended. It turns out that Beecher had written a number of columns for the New York Independent Newspaper, with the ones authored by him denoted with a star. Inevitably, then, this book is a compilation of those starred papers.

Opening the book with care — it is one of the oldest titles in my collection — I steeled myself for flowery, overwrought prose and a lot of reflections of a religious bent (as the title of this blog post suggests). And while these characteristics are present, so, too, is a passion for nature and a delightfully whimsical and occasionally even self-deprecating sense of humor. His essay on books and bookshops (see my previous post) rings amazingly true for me today. And while he was certainly no scientist, he did have a keen command of plant identification and basic botanical nomenclature (both wildflowers and trees) and a working knowledge of common names of birds. Here are two passages on flowering weeds from “A Discourse on Flowers” that opens the Nature section of his book. First, dog fennel, a tall and odoriferous weed I contend with each year on my property in Georgia:

What shall we say of mayweed, irreverently called dog-fennel by some? Its acrid juice, its heavy pungent odor, make it disagreeable; and being disagreeable, its enormous Malthusian propensities to increase render it hateful to damsels of white stockings, compelled to walk through it on dewy mornings. Arise, O scythe, and devour it!

And second, the lowly dandelion that covers my yard with its festive yellow blooms:

You can not forget, if you would, those golden kisses all over the cheeks of the meadow, queerly called dandelions. There are many greenhouse blossoms less pleasing to us than these. And we have reached through many a fence, since we were incarcerated, like them, in a city, to pluck one of these yellow flower drops. Their passing away is more spiritual than their bloom. Nothing can be more airy and beautiful than the transparent seed-globe — a fairy dome of splendid architecture.

His greatest rapture, though, he reserves for the stately Connecticut elms. This extended passage evokes what America has lost, and how different the small town landscape must have been 150 years ago when elms were commonplace:

A village shaded by thoroughly grown elms can not but be handsome. Its houses may be huts; its streets may be ribbed with rocks, or channeled with ruts; it may be as dirty as New York, and as frigid as Philadelphia; and yet these vast, majestic tabernacles of the air would redeem it to beauty. These are temples indeed, living temples, neither waxing old nor shattered by Time, that cracks and shatters stone, but rooting wider with every generation and casting a vaster round of grateful shadow with every summer. We had rather walk beneath an avenue of elms than inspect the noblest cathedral that art ever accomplished. What is it that brings one into such immediate personal and exhilarating sympathy with venerable trees! One instinctively uncovers as he comes beneath them; he looks up with proud veneration into the receding and twilight recesses; he breathes a thanksgiving to God every time his cool foot falls along their shadows. They waken the imagination and mingle the olden time with the present. Did any man of contemplative mood ever stand under an old oak or elm, without thinking of other days, — imagining the scenes that had transpired in their presence? These leaf-mountains seem to connect the past and the present to us as mountain ridges attract clouds from both sides of themselves…

No other tree is at all comparable to the elm. The ash is, when well grown, a fine tree, but clumpy; the maple has the same character. The horse-chestnut, the linden, the mulberry, and poplars, (save that tree-spire, the Lombardy poplar,) are all of them plump, round, fat trees, not to be despised, surely, but representing single dendrological ideas. The oak is venerable by association, and occasionally a specimen is found possessing a kind of grim and ragged glory. But the elm, alone monarch of trees, combines in itself the elements of variety, size, strength, and grace, such as no other tree known to us can at all approach or remotely rival. It is the ideal of trees; the true Absolute Tree! Its main trunk shoots up, not round and smooth, like an over-fatted, lymphatic tree, but channeled and corrugated, as if its athletic muscles showed their proportions through the bark, like Hercules’ limbs through his tunic. Then suddenly the whole idea of growth is changed, and multitudes of long, lithe branches radiate from the crotch of the tree, having the effect of straightness and strength, yet really diverging and curving, until the outermost portions droop over and give to the whole top the most faultless grace. If one should at first say that the elm suggested ideas of strength and uprightness, on looking again he would correct himself, and say that it was majestic, uplifting beauty that it chiefly represented. But if he first had said that it was graceful and magnificent beauty, on a second look he would correct himself, and say that it was vast and rugged strength that it set forth. But at length he would say neither; he would say both; he would say that it expressed a beauty of majestic strength, and a grandeur of graceful beauty.

Such domestic forest treasures are a legacy which but few places can boast. Wealth can build houses, and smooth the soil; it can fill up marshes, and create lakes or artificial rivers; it can gather statues and paintings; but no wealth can buy or build elm trees — the floral glory of New England. Time is the only architect of such structures; and blessed are they for whom Time was pleased to fore-think! No care or expense should be counted too much to maintain the venerable elms of New England in all their regal glory!

Elm trees are not the only living beings lost or diminished since Beecher’s days. Similarly, we are rapidly losing the diversity and number of insects that were once present in the American landscape. Consider this account of a trouting excursion gone awry. Can you imagine encountering this many (and this great a diversity of) grasshoppers on a rural New England fishing trip today?

Still further north is another stream, something larger, and much better or worse according to your luck. It is easy of access, and quite unpretending. There is a bit of a pond, some twenty feet in diameter, from which it flows; and in that there are five or six half-pound trout who seem to have retired from active life and given themselves to meditation in this liquid convent. They were very tempting, but quite untemptable. Standing afar off, we selected an irresistible fly, and with long line we sent it pat into the very place. It fell like a snow-flake. No trout should have hesitated a moment. The morsel was delicious. The nimblest of them should have flashed through the water, broke the surface, and with a graceful but decisive curve plunged downward, carrying the insect with him. Then we should, in our turn, very cheerfully, lend him a hand, relieve him of his prey, and, admiring his beauty, but pitying his untimely fate, bury him in the basket. But he wished no translation. We cast our fly again and again; we drew it hither and thither; we made it skip and wriggle; we let it fall plash like a blundering bug or fluttering moth; and our placid spectators calmly beheld our feats, as if all this skill was a mere exercise for their amusement, and their whole duty consisted in looking on and preserving order.

Next, we tried ground-bait, and sent our vermicular hook down to their very sides. With judicious gravity they parted, and slowly sailed toward the root of an old tree on the side of the pool. Again, changing place, we will make an ambassador of a grasshopper. Laying down our rod, we prepare to catch the grasshopper. That is in itself no slight feat. At the first step you take, at least forty bolt out and tumble headlong into the grass; some cling to the stems, some are creeping under the leaves, and not one seems to be within reach. You step again; another flight takes place, and you eye them with fierce penetration, as if thereby you could catch some one of them with your eye. You can not, though. You brush the grass with your foot again. Another hundred snap out, and tumble about in every direction. There are large ones and small ones, and middling-sized ones; there are gray and hard old fellows; yellow and red ones; green and striped ones. At length it is wonderful to see how populous the grass is. If you did not want them, they would jump into your very hand. But they know by your looks that you are out a-fishing. You see a very nice young fellow climbing up a steeple stem, to get a good look-out and see where you are. You take good aim and grab at him. The stem you catch, but he has jumped a safe rod. Yonder is another creeping among some delicate ferns. With broad palm you clutch him and all the neighboring herbage too. Stealthily opening your little finger, you see his leg; the next finger reveals more of him; and opening the next you are just beginning to take him out with the other hand, when, out he bounds and leaves you to renew your entomological pursuits! Twice you snatch handfuls of grass and cautiously open your palm to find that you have only grass. It is quite vexatious. There are thousands of them here and there, climbing and wriggling on that blade, leaping off from that stalk, twisting and kicking on that vertical spider’s web, jumping and bouncing about under your very nose, hitting you in your face, creeping on your shoes, or turning summersets and tracing every figure of parabola or ellipse in the air, and yet not one do you get. And there is such, a heartiness and merriment in their sallies! They are pert and gay, and do not take your intrusion in the least dudgeon. If any tender-hearted person ever wondered how a humane man could bring himself to such a cruelty as the impaling of an insect, let him hunt for a grasshopper in a hot day among tall grass; and when at length he secures one, the affixing him upon the hook will be done without a single scruple, with judicial solemnity, and as a mere matter of penal justice.

Now then the trout are yonder. We swing our line to the air, and give it a gentle cast toward the desired spot, and a puff of south wind dexterously lodges it in the branch of the tree. You plainly see it strike, and whirl over and over, so that no gentle pull will loosen it. You draw it north and south, east and west; you give it a jerk up and a pull down; you try a series of nimble twitches; in vain you coax it in this way and solicit it in that. Then you stop and look a moment, first at the trout and then at your line. Was there ever anything so vexatious? Would it be wrong to get angry? In fact you feel very much like it. The very things you wanted to catch, the grasshopper and the trout, you could not; but a tree, that you did not in the least want, you have caught fast at the first throw. You fear that the trout will be scared. You cautiously draw nigh and peep down. Yes, there they are, looking at you and laughing as sure as ever trout laughed! They understand the whole thing. With a very decisive jerk you snap your line, regain the remnant of it, and sit down to repair it, to put on another hook, you rise up to catch another grasshopper, and move on down the stream to catch a trout!

In this brief passage, also on the theme of fishing, Beecher gazes longingly at a brook plunging down the mountainside. He urges readers to leave some wild places unfished (untouched). Or then again…

…we are on the upper brink of another series of long down-plunges, each one of which would be enough for a day’s study. Below these are cascades and pools in which the water whirls friskily around like a kitten running earnestly after its tail. But we will go no further down. These are the moun- tain jewels ; the necklaces which it loves to hang down from its hoary head upon its rugged bosom.

Shall we take out our tackle? That must be a glorious pool yonder for trout ! No, my friend, do not desecrate such a scene by throwing a line into it with piscatory intent. Leave some places in nature to their beauty, unharassed, for the mere sake of their beauty. Nothing could tempt us to spend an hour here in fishing; — all the more because there is not a single trout in the whole brook.

To declare Beecher an early conservationist akin to Thoreau would be a stretch, I think. But he does make a strident call for respecting old trees instead of cutting them down. Ultimately, his motivation is less for the sake of the tree itself, however, than for its spiritual significance as a creation of God.

Thus do you stand, noble elms! Lifted up so high are your topmost boughs, that no indolent birds care to seek you; and only those of nimble wings, and they with unwonted beat, that love exertion, and aspire to sing where none sing higher. — Aspiration! so Heaven gives it pure as flames to the noble bosom. But debased with passion and selfishness it comes to bo only Ambition!

It was in the presence of this pasture-elm, which we name the Queen, that we first felt to our very marrow that we had indeed become owners of the soil ! It was with a feeling of awe that we looked up into its face, and when I whispered to myself, This is mine, there was a shrinking as if there were sacrilege in the very thought of property in such a creature of God as this cathedral-topped tree! Does a man bare his head in some old church? So did I, standing in the shadow of this regal tree, and looking up into that completed glory, at which three hundred years have been at work with noiseless fingers! What was I in its presence but a grasshopper? My heart said, “I may not call thee property, and that property mine! Thou belongest to the air. Thou art the child of summer. Thou art the mighty temple where birds praise God. Thou belongest to no man’s hand, but to all men’s eyes that do love beauty, and that have learned through beauty to behold God ! Stand, then, in thine own beauty and grandeur! I shall be a lover and a protector, to keep drought from thy roots, and the ax from thy trunk.”

For, remorseless men there are crawling yet upon the face of the earth, smitten blind and inwardly dead, whose only thought of a tree of ages is, that it is food for the ax and the saw ! These are the wretches of whom the Scripture speaks: “A man was famous according as he had lifted up axes upon the thick trees.“

Thus famous, or rather infamous, was the last owner but one, before me, of this farm. Upon the crown of the hill, just where an artist would have planted them, had he wished to have them exactly in the right place, grew some two hundred stalworth and ancient maples, beeches, ashes, and oaks, a narrow belt-like forest, forming a screen from the northern and western winds in winter, and a harp of endless music for the summer. The wretched owner of this farm, tempted of the Devil, cut down the whole blessed band and brotherhood of trees, that he might fill his pocket with two pitiful dollars a cord for the wood! Well, his pocket was the best part of him. The iron furnaces have devoured my grove, and their huge stumps, that stood like gravestones, have been cleared away, that a grove may be planted in the same spot, for the next hundred years to nourish into the stature and glory of that which is gone.

In other places, I find the memorials of many noble trees slain; here, a hemlock that carried up its eternal green a hundred feet into the winter air; there, a huge double-trunked chestnut, dear old grandfather of hundreds of children that have for generations clubbed its boughs, or shook its nut-laden top, and laughed and shouted as bushels of chestnuts rattled down. Now, the tree exists only in the form of loop-holed posts and weather-browned rails. I do hope the fellow got a sliver in his finger every time he touched the hemlock plank, or let down the bars made of those chestnut rails !

What then, it will be said, must no one touch a tree? must there be no fuel, no timber? Go to the forest for both. There are no individual trees there, only a forest. One trunk here, and one there, leaves the forest just as perfect as before, and gives room for young aspiring trees to come up in the world. But for a man to cut down a large, well-formed, healthy tree from the roadside, or from pastures or fields, is a piece of unpardonable Vandalism. It is worse than Puritan hammers upon painted windows and idolatrous statues. Money can buy houses, build walls, dig and drain the soil, cover the hills with grass, and the grass with herds and flocks. But no money can buy the growth of trees. They are born of Time. Years are the only coin in which they can be paid for. Beside, so noble a thing is a well-grown tree, that it is a treasure to the community, just as is a work of art. If a monarch were to blot out Euben’s Descent from the Cross, or Angelo’s Last Judgment, or batter to pieces the marbles of Greece, the whole world would curse him, and for ever. Trees are the only art-treasures which belong to our villages. They should be precious as gold.

But let not the glory and grace of single trees lead us to neglect the peculiar excellences of the forest. We go from one to the other, needing both ; as in music we wander from melody to harmony, and from many-voiced and intertwined harmonies back to simple melody again.

To most people a grove is a grove, and all groves are alike. But no two groves are alike. There is as marked a difference between different forests as between different communities. A grove of pines without underbrush, carpeted with the fine-fingered russet leaves of the pine, and odorous of resinous gums, has scarcely a trace of likeness to a maple woods, either in the insects, the birds, the shrubs, the light and shade, or the sound of its leaves.

Do I detect, at the close of this passage, incipient thoughts about the diversity of forest ecosystems? Alas, it is a thought he carries no further, beyond remarking on his favorite blending of forest trees.

Ultimately, his thoughts of nature are bounded by his ultimate aim, appreciating God in all his glory. Here, toward the end of the book, Beecher considers the various uses of nature. While he does not identify fully with the utilitarian perspective, he does not reject it, either. Ultimately, he advocates nature appreciation as a form of religious devotion. We will leave him there, pondering the ineffable as the sun sinks low in the sky over New England.

As things go in our utilitarian age, men look upon the natural world in one of three ways: the first, as a foundation for industry, and all objects are regarded in their relations to industry. Grass is for hay, flowers are for medicine, springs are for dairies, rocks are for quarries, trees are for timber, streams are for navigation or for milling, clouds are for rain, and rain is for harvests. The relation of an object to some commercial or domestic economy, is the end of observation. Beyond that there is no interest to it.

The second aspect in which men behold nature, is the purely scientific. We admire a man of science who is so all-sided that he can play with fancy or literality, with exactitudes or associations, just as he will. But a mere man of accuracy, one of those conscientious-eyed men, that will never see any thing but just what is there, and who insist upon bringing every thing to terms; who are for ever dissecting nature, and coming to the physical truths in their most literal forms, these men are our horror. We should as soon take an analytic chemist to dine with us, that he might explain the constituent elements of every morsel that Eve ate; or an anatomist into a social company, to describe the bones, and muscles, and nerves that were in full play in the forms of dear friends. Such men think that nature is perfectly understood when her mechanism is known; when her gross and physical facts are registered, and when all her details are catalogued and described. These are nature’s dictionary-makers. These are the men who think that the highest enjoyment of a dinner would be to be present in the kitchen and that they might see how the food is compounded and cooked.

A third use of nature is that which poets and artists make, who look only for beauty.

All of these are partialists. They all misinterpret, because they all proceed as if nature were constructed upon so meager a schedule as that which they peruse; as if it were a mere matter of science, or of commercial use, or of beauty; whereas these are but single developments among hundreds.

The earth has its physical structure and machinery, well worth laborious study; it has its relations to man’s bodily wants, from which spring the vast activities of industrial life; it has its relations to the social faculties, and the finer sense of the beautiful in the soul; but far above all these are its declared uses, as an interpreter of God, a symbol of invisible spiritual truths, the ritual of a higher life, the highway upon which our thoughts are to travel toward immortality, and toward the realm of just men made perfect that do inherit it.

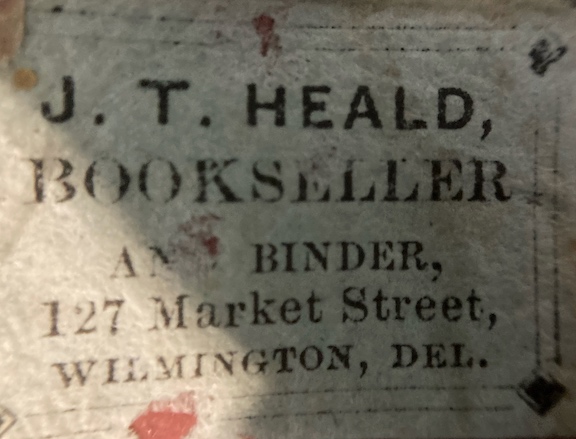

For its vast age, my copy of this book offers few clues as to its history. There is a bookseller stamp for J.T. Heald, Bookseller and Binder, 127 Market Street, Wilmington, Delaware. There is also a signature without a date or other identifying information. The name appears to be Hannah B. Michner. I was unable to locate the name online when searched with Delaware, Pennsylvania,

Wilmington, or Philadelphia. I am not clear if the last name is a maiden name or a name received upon marriage. Nor do I have any hint regarding whether the owner purchased the book new, in Delaware, or used, somewhere else.