We entered the tiny road (for in this kind of hunting a mouse is as good as a mink), and found ourselves descending the woods toward the garden-patch below. Halfway down we came to a great red oak, into a hole at the base of which, as into the portal of some mighty castle, ran the road of the mice. That was the end of it. There was not a single straying footprint beyond the tree.

I reached in as far as my arm would go, and drew out a fistful of pop-corn cobs. So here was part of my scanty crop ! I pushed in again, and gathered up a bunch of chestnut shells, hickory-nuts, and several neatly rifled hazelnuts. This was story enough. There was a nest, or family, of mice living under the slashing pile, who for some good reason kept their stores here in the recesses of this ancient red oak. Or was this some squirrel’s barn being pilfered by the mice, as my barn is the year round ? It was not all plain. But this question, this constant riddle of the woods, small, indeed, in the case of the mouse, and involving no great fate in its solution, is part of our constant joy in the woods. Life is always new, always strange, always fascinating.

It has all been studied and classified according to species. Any one knowing the woods at all would know that these were mice-tracks, the tracks of the white-footed mouse, even, and not the tracks of the jumping mouse, the house mouse, or the meadow mouse. But what is the whole small story of these prints ? What purpose, intention, feeling do they spell? What and why? a hundred times!

But the scientific books are dumb. Indeed, they do not consider such questions worth answering, just as under the species Mus they make no record of the fact that

The present only toucheth thee.

But that is a poem. Burns discovered that Burns, the farmer! The woods and fields are poem-full, and it is largely because we do not know, and never can know, just all that the tiny snow-prints of a wood-mouse may mean, nor understand just what

root and all, and all in all, / the humblest flower is.

The pop-corn cobs, however, were a known quantity, a tangible fact, and falling in with a gray squirrel’s track not far from the red oak, we went on, our game-bag heavier, our hearts lighter at the thought that we, by the sweat of our brow, had contributed a few ears of corn to the comfort of this snowy winter world.

The more I read the works of Dallas Lore Sharp, the more I appreciate his flair for seeing both the scientific and the poetic elements in nature. The marriage of the two, as I have observed in many past blogs, was a common theme in American nature writing of this period. Sometimes the combinations were forced, like an arranged marriage between polar opposites, enforced by an author who is either a poet or a scientist, but rarely both at once. And sometimes a lovely description is marred by bad poetry, or a poetic account is marred by poor science. But in Sharp’s finest work, the two seem supremely natural when joined together. Neither alone can capture the complexity, majesty, wonder, and magic of nature, either in our own backyard or in the remote wilds. (In Sharp’s case, mostly rural nature, close at hand.)

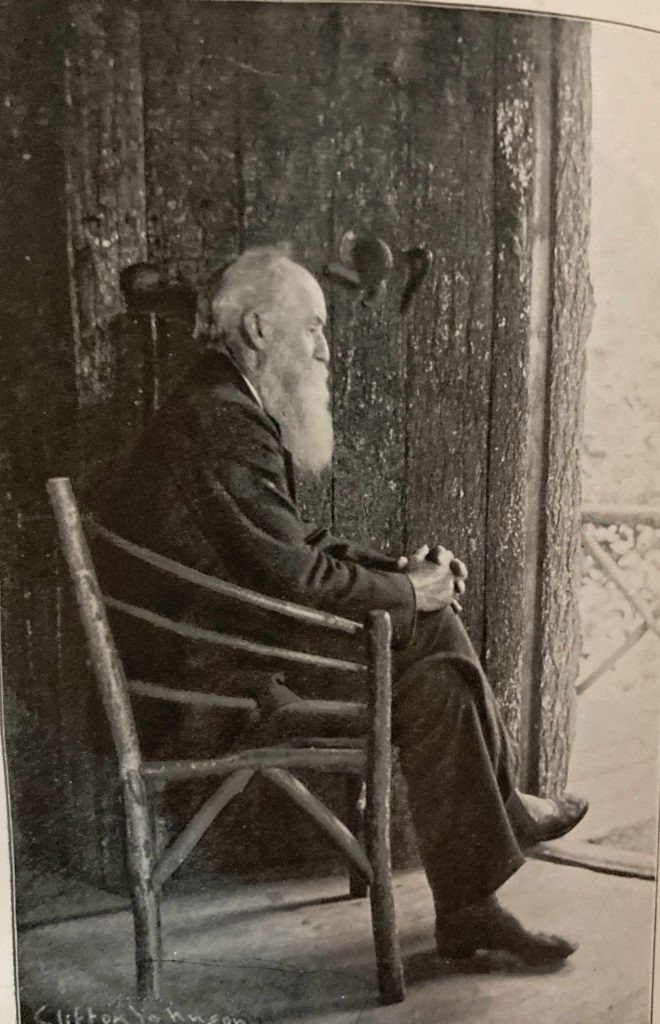

This volume of Sharp’s essays is a trove of delightful writing. If I had to single out a few for praise, I would certainly highlight “Turtle Eggs for Aggasiz”, a somewhat humorous second-hand account of a naturalist’s frantic effort to secure turtle eggs for the renowned scientist Louis Agassiz, under the stipulation that the eggs had to have been laid no more than four hours previously. This essay, which is about as close to a page-turner as nature writers from this era ever achieve, is frequently anthologized. (Frequently, that is, relative to practically anything else I have read for the blog thus far.) Another essay celebrates John Burroughs; however, he borrowed heavily from it for his eulogy to Burroughs, The Seer of Slabsides, after the author’s death. The title essay, “The Face of the Fields”, celebrates the childlike quality of nature, in contrast to adults’ feelings of fear and dread we feel as we confront death in its many guises:

We cannot go far into the fields without sight-ing the hawk and the snake, the very shapes of Death. The dread Thing, in one form or another, moves everywhere, down every wood-path and pasture-lane, through the black close waters of the mill-pond, out under the open of the winter sky, night and day, and every day, the four seasons through. I have seen the still surface of a pond break suddenly with a swirl, and flash a hundred flecks of silver into the light, as the minnows leap from the jaws of the pike. Then a loud rattle, a streak of blue, a splash at the centre of the swirl, and I see the pike, twisting and bending in the beak of the kingfisher. The killer is killed; but at the mouth of the nest-hole in the steep sandbank, swaying from a root in the edge of the turf above, hangs the black snake, the third killer, and the belted kingfisher, dropping the pike, darts off with a cry. I have been afield at times when one tragedy has followed another in such rapid and continuous succession as to put a whole shining, singing, blossoming world under a pall. Everything has seemed to cower, skulk, and hide, to run as if pursued. There was no peace, no stirring of small life, not even in the quiet of the deep pines; for here a hawk would be nesting, or a snake would be sleeping, or I would hear the passing of a fox, see perhaps his keen hungry face an instant as he halted, winding me.

Fox and snake and hawk are real, but not the absence of peace and joy except within my own breast. There is struggle and pain and death in the woods, and there is fear also, but the fear does not last long; it does not haunt and follow and terrify; it has no being, no substance, no continu- ance. The shadow of the swiftest scudding cloud is not so fleeting as this shadow in the woods, this Fear. The lowest of the animals seem capable of feeling it; yet the very highest of them seem incapable of dreading it; for them Fear is not of the imagination, but of the sight, and of the passing moment.

The present only toucheth thee!

It does more, it throngs him our fellow mortal of the stubble field, the cliff, and the green sea. Into the present is lived the whole of his life — none of it is left to a storied past, none sold to a mortgaged future. And the whole of this life is action; and the whole of this action is joy. The moments of fear in an animal’s life are moments of reaction, negative, vanishing. Action and joy are constant, the joint laws of all animal life, of all nature, from the shining stars that sing together, to the roar of a bitter northeast storm across these wintry fields.

We shall get little rest and healing out of nature until we have chased this phantom Fear into the dark of the moon. It is a most difficult drive. The pursued too often turns pursuer, and chases us back into our burrows, where there is nothing but the dark to make us afraid. If every time a bird cries in alarm, a mouse squeaks with pain, or a rabbit leaps in fear from beneath our feet, we, too, leap and run, dodging the shadow as if it were at our own heels, then we shall never get farther toward the open fields than Chuchundra, the muskrat, gets toward the middle of the bun- galow floor. We shall always creep around by the wall, whimpering.

But there is no such thing as fear out of doors. There was, there will be; you may see it for an instant on your walk to-day, or think you see it; but there are the birds singing as before, and as before the red squirrel, under cover of large words, is prying into your purposes. The universal chorus of nature is never stilled. This part, or that, may cease for a moment, for a season it may be, only to let some other part take up the strain; as the winter’s deep bass voices take it from the soft lips of the summer, and roll it into thunder, until the naked hills seem to rock to the measures of the song.

As nature lives only in the moment, fear and dread are largely absent. The predator strikes and kills, then death departs again — its presence a fleeting shadow, quickly forgotten again. At the close of the essay, Sharp reprises this theme in a haunting, poetic passage that explains the meaning of the essay title:

Life, like Law and Matter, is all of one piece. The horse in my stable, the robin, the toad, the beetle, the vine in my garden, the garden itself, and I together with them all, come out of the same divine dust ; we all breathe the same divine breath; we have our beings under the same divine law; only they do not know that the law, the breath, and the dust are divine. If I do know, and yet can so readily forget such knowledge, can so hardly cease from being, can so eternally find the purpose, the hope, the joy of life within me, how soon for them, my lowly fellow mortals, must vanish all sight of fear, all memory of pain! And how abiding with them, how compelling, the necessity to live! And in their unquestioning obedience what joy!

The face of the fields is as changeful as the face of a child. Every passing wind, every shifting cloud, every calling bird, every baying hound, every shape, shadow, fragrance, sound, and tremor, are so many emotions reflected there. But if time and experience and pain come, they pass utterly away; for the face of the fields does not grow old or wise or seamed with pain. It is always the face of a child, asleep in winter, awake in summer, a face of life and health always, if we will but see what pushes the falling leaves off, what lies in slumber under the covers of the snow; if we will but feel the strength of the north wind, and the wild fierce joy of the fox and hound as they course the turning, tangling paths of the woodlands in their race with one another against the record set by Life.

One other particularly noteworthy essay in this volume is “The Nature-Writer”, which sheds light upon the character of the Nature Writing Movement of the time. Early in the essay, Sharp observes that “the nature-writer has now evolved into a distinct, although undescribed, literary species.” Sharp goes on to attempt to elucidate what characterizes him (or her, though usually him):

…the nature-writer, while he may be more or less of a scientist, is never mere scientist — zoologist or botanist. Animals are not his theme; flowers are not his theme. Nothing less than the universe is his theme, as it pivots on him, around the distant boundaries of his immediate neighborhood.

His is an emotional, not an intellectual, point of view; a literary, not a scientific, approach; which means that he is the axis of his world, its great circumference, rather than any fact any flower, or star, or tortoise. Now to the scientist the tortoise is the thing: the particular species Tbalassochelys kempi; of the family Testudinidse; of the order Chelonia; of the class Reptilia; of the branch Vertebrata. But the nature-writer never pauses over this matter to capitalize it. His tortoise may or may not come tagged with this string of distinguishing titles. A tortoise is a tortoise for a’ that, particularly if it should happen to be an old Sussex tortoise which has been kept for thirty years in a yard by the nature-writer’s friend, and which [quoting Gibert White] “On the 1st November began to dig the ground in order to the forming of its hybernaculum, which it had fixed on just beside a great tuft of hepaticas.”

The nature-writer also becomes deeply familiar with a particular spot of Earth, inhabiting it deeply and sharing its lessons with readers.

It is characteristic of the nature-writer… to bring home his outdoors, to domesticate his nature, to relate it all to himself. His is a dooryard universe, his earth a flat little planet turning about a hop-pole in his garden — a planet mapped by fields, ponds, and cow-paths, and set in a circumfluent sea of neighbor townships, beyond whose shores he neither goes to church, nor works out his taxes on the road, nor votes appropriations for the schools.

He is limited to his parish because he writes about only so much of the world as he lives in, as touches him, as makes for him his home…

It is a large love for the earth as a dwelling-place, a large faith in the entire reasonableness of its economy, a large joy in all its manifold life, that moves the nature-writer. He finds the earth most marvelously good to live in — himself its very dust; a place beautiful beyond his imagination, and interesting past his power to realize — a mystery every way he turns. He comes into it as a settler into a new land, to clear up so much of the wilderness as he shall need for a home.

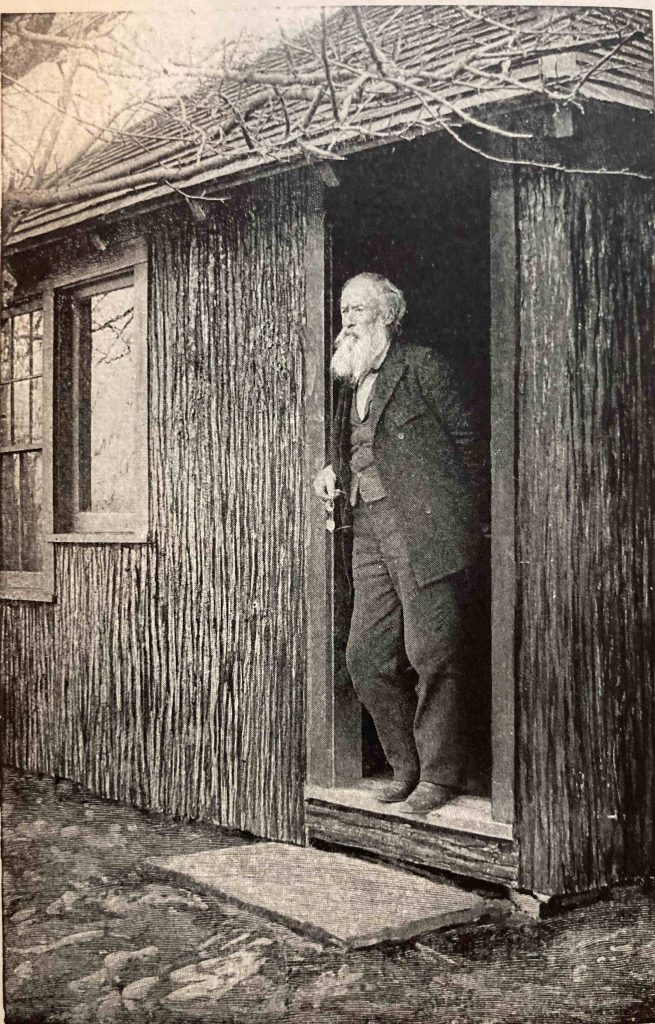

Alas, Sharp’s examples of nature writers are mostly the familars — Gilbert White, Henry David Thoreau, and John Burroughs. (“In none of our nature-writers… is this love for the earth more manifest than in John Burroughs. It is constant and dominant in him, an expression of his religion.”) Later in the essay, Sharp does make brief reference to Dr. C. C. Abbott and Maruice Maeterlinck (Belgian playwright and author of The Life of the Bee). But no others make the cut — not even Bradford Torrey. Alas, “the sad case with much nature-writing… is that it not only fails to answer to genuine observation, but it also fails to answer to genuine emotion. Often as we detect the unsound natural history, we much oftener are aware of the unsound, the insincere, art of the author.” Here, it would have been most helpful for Sharp to identify a few particular authors and their works, as a caution to the reader. Which of the many nature authors I have read, I wonder, would Sharp have placed in this category?

Sharp closes his essay with this poetic passage about good nature writing. Essentially, good nature writing is true to life, expressing an abiding love of the natural world.

Good nature-literature, like all good literature, is more lived than written. Its immortal part hath elsewhere than the ink-pot its beginning. The soul that rises with it, its life’s star, first went down behind a horizon of real experience, then rose from a human heart, the source of all true feeling, of all sincere form. Good nature-writing particularly must have a pre-literary existence as lived reality; its writing must be only the necessary accident of its being lived again in thought. It will be something very human, very natural, warm, quick, irregular, imperfect, with the imperfections and irregularities of life. And the nature-writer will be very human, too, and so very faulty; but he will have no lack of love for nature, and no lack of love for the truth. Whatever else he does, he will never touch the flat, disquieting note of make-believe. He will never invent, never pretend, never pose, never shy. He will be honest which is nothing unusual for birds and rocks and stars ; but for human beings, and for nature-writers very particularly, it is a state less common, perhaps, than it ought to be.