Lately I have been pondering the analogy of the photographer as shaman. In many indigenous cultures, particularly those in northern Asia and parts of North and South America, shamans were guides and healers who would venture into the spirit world underlying everyday reality in order to bring back messages to restore order and balance to an individual or group. They would alter their consciousness, passing into a trance by such means as drumming, chanting, and/or the ingestion of hallucinogens. Within a trance state, they would encounter and interact with spiritual beings and forces, gathering the information needed to solve community problems and benefit others.

In many ways, of course, my outing to Piney Woods Church Road is anything but a shamanic journey of “religious ecstasy” (as the late historian Mercea Eliade wrote). I do not chant or drum while walking the roadway, though I might hum a bit or even talk to myself from time to time. Nor do I ingest anything out of the ordinary before setting out — maybe a cup of coffee or tea, but nothing more. What I return with — a collection of digital images — isn’t intended to solve any of the world’s ills or heal anyone. Yet I have found that much of my time spent walking Piney Woods Church Road from one end to the other and back, I spend noticing my surroundings in a way that is different from how I go through the rest of my day, and different from how I would notice (or fail to notice) the same road during countless dog walks over the past seven years. My eye is drawn to unusual compositions, and I feel compelled to engage with the place in different ways. Yesterday I lay down at the end of a driveway to photograph the landscape at eye level, a concrete wasteland with a line of pines beyond. Certainly, what I bring back continues to seem more amazing and delightful than I would have expected as a result of venturing there before beginning this project. Does the landscape of such a seemingly nondescript gravel road really offer all that? So far, I have gathered sixteen very different images to share on this blog (plus three extras, including the photo at the start of this article, taken on January 15th). In my opinion, they are among the best photographs I have ever taken. Yet I have over the years traveled the world in search of its wonders (particularly geological ones), from Australia and New Zealand to Belize and Bolivia, and from Arizona and California to Florida and Maine.

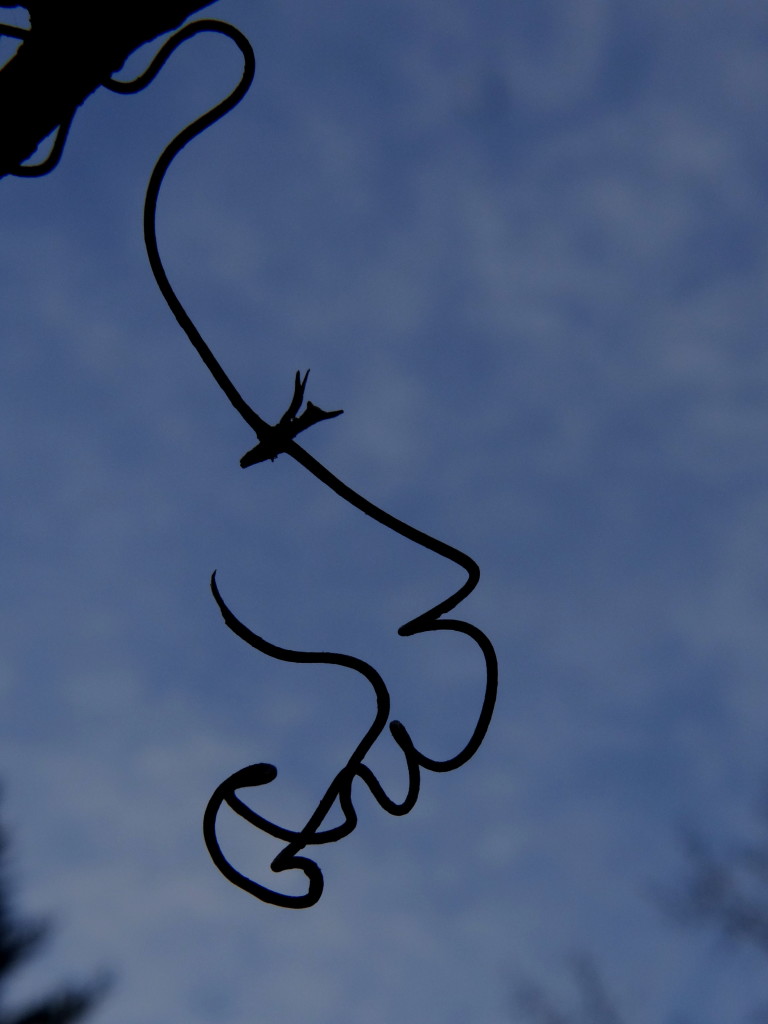

Certainly I do not enter the spirit world on any of my outings. I remain firmly grounded in the everyday of my small corner of Fulton County, in the Piedmont of Georgia. On my walk I see potholes and mud, barbed wire and drooling cows. Yet I still find wonders there, hiding beneath the first glance we might make. A pine warbler perches for just a moment on a fence wire, and a persimmon leaf lit from behind by the morning sun looks like a stained glass window. Slowing down, lost in the moment, I find flow, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi terms it, a condition of heightened focus and immersion in our surroundings. In the state of flow, creative and wonderful experiences can happen, and happiness be found.

Unlike the shaman who acts primarily to aid others, the daily journeys I take are ultimately for my own benefit. They are intended to help me develop a discipline I have previously been lacking, committing me to a project that requires daily engagement with my immediate environment. From the very beginning, I gambled that the benefits I would receive from my discoveries along the way would outweigh the sacrifices I must make, particularly an entire year spent without taking any trips longer than a day or so. Thus far, I feel that I have been repaid for my efforts, in spades. And I have been delighted to find that readers to my blog have enjoyed the photos I have shared. (I have found that cows and sunsets tend to be the biggest hits — I await a composition involving both.) Perhaps that instinct that urges many of us to hit the road from time to time in our lives might be met much closer to home than we might imagine. Something akin to a shamanic journey might be possible without even leaving our own neighborhoods.